Topic 7 Platyhelminthes II - Plattsburgh State Faculty and Research

advertisement

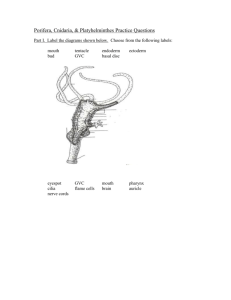

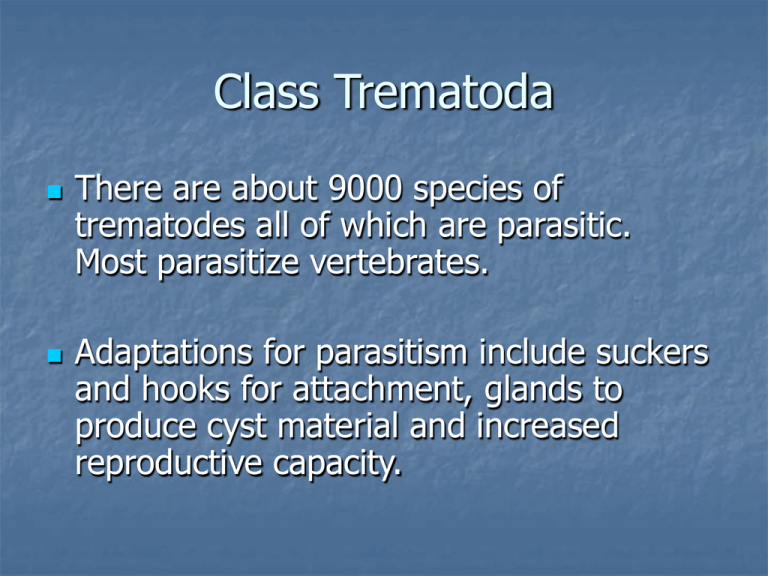

Class Trematoda There are about 9000 species of trematodes all of which are parasitic. Most parasitize vertebrates. Adaptations for parasitism include suckers and hooks for attachment, glands to produce cyst material and increased reproductive capacity. Sheep liver fluke Class Trematoda Structurally, trematodes are similar to turbellarians having a well developed digestive system and similar nervous, excretory, and reproductive systems. However, a major difference is the tegument. Tegument The tegument (found in all parasitic Platyhelminthes) is a nonciliated, cytoplasmic syncytium that overlays layers of muscle. The syncytium represents extensions of cells that are located below the muscle in the parenchyma. The tegument protects the parasite against its host (e.g. against digestive enzymes). Figure 14.05 8.5 Digenean Trematodes There are three subclasses of Trematodes, but two are small, poorly studied groups. The third group, the Digenea, however is a large group of major medical and economic importance. Digenean Trematodes The flukes have a complex life cycle in which a snail is the first (or intermediate) host and a vertebrate the final (or definitive host). The definitive host is one in which the fluke reproduces sexually. Digenean Trematodes In some species there may be 2 or 3 intermediate hosts before the definitive host is reached. Trematodes inhabit a variety of sites in their hosts including the digestive tract, respiratory tract, circulatory system, urinary tract, and reproductive tract. Digenean Trematodes Digenean life cycles are very complex and the fluke passes through numerous stages. Digenean Trematodes A typical example would include the following stages: Adult Egg (or shelled embryo) shed into water Miracidium: a free swimming, ciliated larva that finds and penetrates a snail intermediate host Sheep liver fluke egg (top) and miracidium (bottom). http://cal.vet.upenn.edu/projects/paraav/images/lab6-227.jpg Digenean Trematodes Sporocyst: reproduces asexually in intermediate host producing more sporocysts or another asexually reproducing stage called a redia. Redia produce more redia or cercariae. Cercariae leave the intermediate host and swim. Then they penetrate the skin of another intermediate host or the definitive host. Adult Fasciola hepatica Sheep liver fluke (above) Redia (right) http://cal.vet.upenn.edu/projects/paraav/images/lab6-227.jpg Digenean Trematodes Cercariae that enter an intermediate host may encyst in muscle and wait to be consumed by the definitive host or may leave the intermediate host to actively search for the definitive host. Cercariae that enter the definitive host make their way to their desired home and develop into an adult fluke which reproduces sexually and produces eggs. http://www.biology-blog.com/images/blogs/trematode-cercaria-482810.jpg Clonorchis liver fluke Clonorchis is the most important liver fluke to infect humans. Common in much of Asia (including China, Japan and southern Asia). Adult flukes live in the bile passages and shelled miricidia pass out in feces. The miricidia enter snails eventually leave the snails as cercariae and find a fish where they encyst. If fish is eaten raw or poorly cooked the person becomes infected Figure 14.12 8.8 How do flukes manipulate their hosts? Many parasites infect an intermediate host that needs to be eaten by the definitive host for the parasite to complete its lifecycle. There are many instances of parasites altering their intermediate host’s behavior to make it more vulnerable to a predator (the definitive host). Such behavior is widespread in flukes. How do flukes manipulate their hosts? In the Carpenteria Salt Marshes in southern California lives the fluke Euhaplorchis californiensis. It has a life cycle that includes two intermediate hosts, first the California Horn Snail and then the California killifish and a final host which can be any of a variety of fish eating birds. How do flukes manipulate their hosts? The fluke leaves its definitive host as an egg in bird droppings which are eaten by the fluke’s first intermediate host, the snail. The fluke then castrates the snail (preventing it from diverting energy into eggs and away from the parasite). The fluke then reproduces asexually and sheds cercariae into the water. How do flukes manipulate their hosts? The cercariae seek out the next intermediate host the killifish and latch onto the fish’s gills. Each cercaria works its way into a blood vessel and explores until it finds a nerve which it then follows until it reaches the fish’s brain. How do flukes manipulate their hosts? The cercariae don’t penetrate the brain but sit on top of it. Then they wait for the fish to be eaten by a bird. Once eaten by a bird they break out of the fish’s head and move into the bird’s gut where they produce eggs that continue the cycle How do flukes manipulate their hosts? The cercariae sitting on the bird’s brain apparently don’t sit passively waiting. Killifish when swimming occasionally shimmy and jerk around flashing their bellies. Those infected with cercariae are four times more likely to do so than noninfected fish. How do flukes manipulate their hosts? In field experiments in which penned fish were made available to foraging birds infected fish were 30 times (!) more likely to be eaten than uninfected fish. How do flukes manipulate their hosts? Research on how the flukes alter the fish’s behavior has shown that the flukes produce powerful molecular signals called fibroblast growth factors. These interfere with the growth of nerves and may be the mechanism the flukes use. Schistosomiasis Schistosomiasis (also known as bilharzia) is an infection with blood flukes and is a major infectious diseases. More then 200 million people are infected worldwide with these flukes, which they acquire swimming or walking in water in which the intermediate snail host lives Schistosomiasis Schistosome eggs enter the water when infected people urinate or defecate in or near water. Eggs hatch and the miracidium seeks out a snail. Inside the snail the parasite develops into a sprocyst and asexual reproduction takes place. Cercaria eventually are released into the water. Schistosome life cycle. Schistosomiasis When a schistosome cercaria swims it takes care to avoid UV light which can damage it, but is very sensitive to the scent of humans. When it senses molecules from human skin it swims rapidly and jerks around looking for the person. When it makes contact it releases chemicals that soften the skin and it burrows in shedding its tail at the same time. Schistosomiasis The fluke searches until it finds a capillary and enters it. The capillary is only barely wide enough for the fluke and it moves along using its pair of suckers. Eventually, it reaches a larger blood vessel in which it can float until it reaches the lungs and enters an artery and eventually makes its way to the liver. Schistosomiasis Once in the liver, the fluke feeds on blood and begins to mature and develops ovaries or testes depending on its sex. The fluke grows dozens of times larger in the course of a few weeks and then begins to search for a mate. Schistosomiasis The fluke produces chemicals to attract members of the opposite sex. Females are slender and delicate, whereas males are much bigger and have a spiny trough or groove into which the female fits and locks in. Figure 14.13 8.9a and b Schistosomiasis Once paired up, the pair mature sexually and travel from the liver to a permanent home that is species-specific. In Schistosoma mansoni it is near the large intestine, in S. haemotobium it is the bladder, and in S. nasale, a blood fluke of cows, it is the nose. Schistosomiasis Once established the pair remain in situ for the rest of their lives. The male consumes blood and feeds the female most of it, which she turns into eggs, which pass out of the host and can begin the life cycle again. Schistosomiasis Schsitosomiasis has a low mortality rate, but it is a chronic illness that debilitates the infected person. Symptoms can include anemia, diarrhea, fever, fatigue and van result in organ damage. In children infection can result in reduced growth and mental development. Schistosomiasis Schistosomiasis occurs in tropical countries worldwide. It can be treated with oral drugs, but a lot of attention has focused on developing a vaccine and on controlling the snails which are the disease reservoir. Do trematode parasites favor sex in hosts? Lively (1992) studied New Zealand freshwater snail. Host to parasitic trematodes. Trematodes eat host’s gonads and castrate it which imposes strong selection pressure. Snail populations contain both obligate sexually and asexually reproducing females. Do trematode parasites favor sex in hosts? Proportion of sexual vs asexual females varies from population to population. Frequency of trematode infections varies also. Do trematode parasites favor sex in hosts? If evolutionary arms race favors sex, then sexually reproducing snails should be commoner in populations with high rates of trematode infections. Results match predictions. White slice indicates frequency of males and thus sexual reproduction Frequency of males increases with increasing rates of trematode infection. Class Monogenea The monogenetic flukes were previously classified as on order of the Trematoda, but recent work suggests they are more closely related to cestodes (tapeworms). Monogeneans are small (usually < 2cm) typically external parasites of fish that clamp onto the gills using a hooked organ (often with suckers) called an opisthaptor. Some also parasitize the urinary bladder or rectum of frogs and turtles; there is a species that parasitizes squid and one that attaches to the eyeball of hippopotomuses. Figure 14.16 8.11 Monogenean Fluke Class Monogenea Unlike the trematodes, Monogeneans have only a single host (hence “Mono” in the name). Most feed on the host’s epidermis using their protrusible pharynx, but some are blood feeders. Monogeneans are hermaphrodites (male organs develop first) and can move around a host in search of a mate (they will also self-fertilize). The egg hatches into a ciliated larva (an oncomiracidium) which seeks out its host in the water. http://www.sci.sdsu.edu/salton/ssmudgyr14Lg.gif Gyrodactylus olsoni on the gill filament of longjaw mudsucker, SEM. a - general view Class Monogenea Monogeneans typically occur at low levels on fish and so do not inflict serious harm. However, in fish farms, infestations may become very heavy and lead to significant mortality. Class Cestoda (tapeworms) Tapeworms are parasites of the vertebrate digestive tract and about 4000 species are known. Almost all tapeworms require at least two hosts with the definitive host being a vertebrate, although intermediate hosts can be invertebrates. Class Cestoda Members of the Class Cestoda (tapeworms) are quite different in appearance from the other members of the Platyhelminthes. They have long, flat, tape-like bodies composed of a scolex for attaching to their host and a chain of many reproductive units or proglottids called a strobila. New proglottids form behind the scolex and the strobila may become extremely long. Figure 14.18 8.12 Tapeworm scolex Hooks Suckers The scolex is equipped with suckers and hooks that enable it to grip onto its host’s intestines. Class Cestoda Tapeworms live in the intestines and because they are immersed in digested food lack a digestive system of their own. Instead they simply absorb food across their tegument. Class Cestoda To facilitate the absorption of food a tapeworm’s tegument has huge numbers of tiny projections called microtriches, which are broadly similar to the microvilli of the vertebrate intestine. They similarly increase the surface area of the tegument for absorption. Figure 14.17 8.13 Class Cestoda Tapeworms are usually monoecious (have both male and female reproductive organs). A proglottid is fertilized by another proglottid in the same or a different strobila. Shell-encased embryos form in the uterus and exit the proglottid via a uterine pore or the entire proglottid may detatch and pass out of the host. Figure 14.20 8.14 Human tapeworms Humans are definitive hosts to several tapeworms including the beef tapeworm Taenia saginata, pork tapeworm T. solium, and fish tapeworm Diphyllobothrium latum. Human tapeworms The lifecycles of these parasites are similar. Shelled larvae are shed into the environment. These are consumed by the intermediate host and the larvae (oncospheres) hatch, bury into blood vessels and make their way to skeletal muscle or the body cavity where they encyst becoming so called “bladder worms” or cysticerci. http://www.medirabbit.com/EN/GI_diseases/Parasitic_diseases/Tape_cyst.jpg Tapeworm cysticerci in body cavity of a rabbit Human tapeworms The encysted larva develops an invaginated scolex and waits, perhaps for years, for its host to be eaten. If the meat is uncooked the cysticercus extends its scolex, attaches to the wall of the intestine and within 2-3 weeks matures and begins growing and producing eggs. A tapeworm may be many meters long and live for years. Figure 14.19 8.15 Adult cestodiasis Cestodiasis is the term for being infected with a cestode. Adult cestodiasis occurs when a human is infected with an adult tapeworm. Adult cestodiasis is the commonest form and is generally not very harmful However, heavy infestation can lead to physical damage to the wall of the gut or perhaps blockage of the intestines. Larval cestodiasis Under poor sanitary conditions, a person with adult cestodiasis may infect themselves with tapeworm eggs (or someone else may infect them). This infection is called larval cestodiasis and is potentially very serious. Humans as intermediate hosts (larval cestodiasis) Humans may become intermediate hosts for tapeworms with potentially disastrous consequences if they consume shelled larvae in contaminated food. In an evolutionarily unfamiliar environment, cysticerci may encyst in inappropriate locations such as the brain, which is frequently fatal. Figure 14.21 Cysticerci in human brain 8.16 Tapeworm manipulations of hosts Continuing the theme of parasite manipulations we’ve seen this semester it’s not surprising that some tapeworms also manipulate their hosts to ensure they can complete their lifecycles. A good example is the tape worm Hymenolepis diminuta, which parasitizes rats and flour beetles. Tapeworm manipulations of hosts Adults live in the bowels of rats (where they can grow to 45 cm in length) and produce eggs which pass out of the gut in rat droppings. Beetles are attracted to, and eat, rat droppings that contain tapeworm eggs, by an apparently highly attractive scent. Tapeworm manipulations of hosts Not clear whether the eggs, adult tapeworms, or rat host produce this scent, but beetles strongly prefer egg-containing feces to those that are egg free. Once in the beetle, the tapeworm produces several chemicals that sterilize female beetles by blocking the flow of nutrients that allows egg formation. Tapeworm manipulations of hosts In order to reach its final host the tapeworm needs to ensure that the beetle gets eaten by the definitive host, a rat. The tapeworm produces chemicals, which make the beetle less likely to conceal itself as well as sluggish and slow to escape if attacked. Tapeworm manipulations of hosts As a final trick the tapeworm also inactivates the beetle’s last line of defense. Flour beetles have glands in the abdomen that spray a foul-tasting liquid, which often will cause a rat to spit out a beetle it has started to eat. The tapeworm blocks the gland that makes this chemical, so that the beetle doesn’t taste bad to the rat and is consumed.