Adulthood PP

advertisement

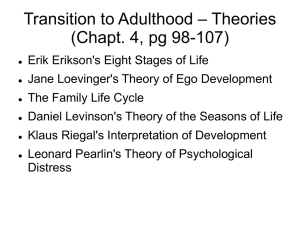

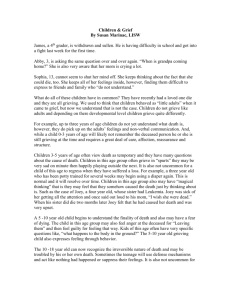

Finishing off The Life Cycle Erikson stages 5-8 Levinson Criticisms of Levinson Death & Bereavement References • Active Psychology Irene Taylor (Ed) • Developmental psychology McIlveen and Goss • Care in Practice Erikson Your Life Span • Exercise • Draw a lifeline on a sheet of paper and identify what were the critical events for you in shaping your life. Exercise • How would you define ageing? Is it a positive or negative process? What is the view held in our society? How old do you feel? Answer the following questions on 'The Ages of Me' taken from Kastenbaum (1979): 1 2 3 4 5 6 In other people's eyes, I look as though I am about _____ years of age. In my own eyes, I judge my body to be like that of a person of about ___ years of age. My thoughts and interests are like those of a person about ___ years of age. My position in society is like that of a person about ___ years of age. Deep down inside, I really feel like a person about ___ years of age. and just one more question: I would honestly prefer to be about __years of age. Life Span Approach Life Span Approach • Bakes, cited in Lewis (1996), noted three main influences (see figure 23.8): • normative age-graded influences which refers to experiences due to biological maturation (such as puberty) or cultural norms (such as age of starting school) • normative history-related influences which demonstrate the effects of generational changes; for example, the lower age of puberty over the last century (biological), and the raising of the school leaving age from 14 years to 16 years (and later for many), since the Second World War • non-normative life-events are such critical life-events which do not necessarily affect everyone, such as a motor accident or divorce, which nevertheless influence the course of development. Critical Life Events • Neugarten (1987) distinguished between: normative changes such as leaving school, marriage, parenting, retirement non-normative changed such as divorce, sudden death, unemployment. Schlossberg 1984, 1989) noted four kinds of transition: • Anticipated transitions which are events planned for and rehearsed, such as going to school, starting a job, getting married, having a child. • Unanticipated transitions which are unexpected events not allowing for preparation, such as losing a job, failing an exam, enforced retirement. • Non-event transitions which are expected changes which do not occur, such as not getting married, not being able to have children, an expected promotion which doesn't occur, retirement not being possible because the income is needed. • Chronic hassle transitions in which situations can result in a long drawn-out period before action can be taken, such as marriage breakdown, terminal illness in someone close, problems in the Importance of Looking at Adaptations • This approach recognises that adaptation is necessary for all these transitions, that what is an expected event for one person may be unexpected by another, and that not all transitions create a crisis. Exercise • Social Re-adjustment Scale Levinson . • Season’s of a Man’s Life Approach to Early and Middle Adulthood Levinson’s Stages Levinson & Erikson Mid- life Crisis • 'They question nearly every aspect of their lives and feel that they cannot go on as before. They will need several years to form a new path or modify the old one'. Mid-Life Crisis • Like Erikson, Levinson and his colleagues see crisis as inevitable. As they note: • 'It is not possible to get through middle adulthood without having at least a moderate crisis either the mid-life transition or the age-50 transition'. • They also see crisis as necessary. If we do not soul searching, we will: • 'pay the price in a later developmental a progressive withering of the self and structure minimally connected to the self. First Criticism of Levinson • Some researchers found the mid-life crisis to be not as universal as Levinson found, and that only about 10% of people feeling they had experienced a crisis. • Rutter suggests that going through middle age without a crisis is actually a predictor of favourable future development • i.e. lack of emotional disturbance predicts better functioning. Two other components of the mid life crisis • The first is a wide range of adaptations in the life pattern. • Some of these stem from role changes that produce fairly drastic consequences, such as divorce, remarriage, a major occupational change, redundancy or serious illness. • Others are more subtle, and include the ageing and likely death of parents, • the new role of grandparent, • and the sense of loss which sometimes occurs when all of the children have moved away from the family home Mid Life Crisis • The second component of the mid-life crisis is the significant change in the internal aspects of our life structure which occurs regardless of external events. • This involves reappraising our achievements and remaining ambitions, especially those to do with work and the relationship with our sexual partner. • A fundamental development at this time is our realisation that the final authority for life rests with us. THE SEASONS OF A WOMAN'S LIFE Women • The age-30 transition is as important for women as men. • The evidence suggests that women who give marriage and motherhood top priority in their 20s tend to develop more individualistic goals for their 30s. • However, those who are career-oriented early on in adulthood tend to focus on marriage and family concerns. • Generally, the transitory instability of the early 30s lasts longer for women than for men, and 'settling down' is much less clear cut. • Trying to integrate career and marriage/family responsibilities is very difficult for most women, who experience greater conflicts than their husbands are likely to do. Comparison of Erikson & Levinson Bereavement • The three phases of 'griefwork' • 1 Disbelief and shock: This phase can last for a few days and involves the refusal to accept the truth of what has happened. • 2 Developing awareness: This is the gradual realisation and acknowledgement of what has happened. This phase is often accompanied by feelings of guilt, apathy, exhaustion and anger. • 3 Resolution: In this phase, the bereaved individual views the situation realistically, begins to cope without the deceased, establishes a new identity and comes to accept fully what has happened. This phase marks the completion of 'griefwork'. • (Based on Engel, 1962) de Croot's nine components of grief • • • • • 1 Shock: Usually the first response, most often described as a feeling of 'numbness'. Can also include pain, calm, apathy, depersonalisation and derealisation. It is as if the feelings are so strong that they are 'turned off; can last from a few seconds to several weeks. 2 Disorganisation: The inability to do the simplest thing or, alternatively, organising the entire funeral and then collapsing. 3 Denial: Behaving as if the deceased were still alive, a defence against feeling too much pain, usually an early feature of grief but one that can recur any time. A common form of denial is searching behaviour, e.g. waiting for the deceased to come home, or having hallucinations of them. 4 Depression: Emerges as the denial breaks down but can occur, usually less frequently and intensely, at any point during the grieving process. Either 'desolate pining' (a yearning and longing, an emptiness 'interspersed with waves of intense psychic pain') or 'despair' (feeling of helplessness, the blackness of the realisation of powerlessness to bring back the dead). de Croot's nine components of grief • 5 Guilt: Can be both real and imagined, for actual neglect of the deceased when they were alive or for angry thoughts and feelings. • 6 Anxiety: Fear of losing control of one's feelings, of going mad or more general apprehension about the future (changed roles, increased responsibilities, financial worries, etc.). • 7 Aggression: Irritability towards family and friends, outbursts of anger towards God or fate, doctors and nurses, the clergy or even the person who has died. • 8 Resolution: An emerging acceptance of the death, a 'taking leave of the dead and ant| acceptance that life must go on'. " • 9 Reintegration: Putting acceptance into practice by reorganising one's life in which the deceased has no place. (However, pining and despair, etc. may reappear on anniversaries, birthdays, etc.). Four Abnormal Patterns of Grief • Prolonged incapacitating grief • Exaggerated Numbness • Neurotic Forms of Emotional distress – fear of being alone, feelings of depersonalisation (feeling unreal) • Physical Symptoms – Murray Parkes found widows consulted GPs much more often in the six months after bereavement. Indeed there is an increased risk of death in these 6 months Preparing for Death • Most adolescents and young adults rarely think about their own death, since it is an event far removed in time. Barrow and Smith (1979) have suggested that some people even engage in an illusion of immortality and completely avoid confronting the fact that their own days are numbered. • As people age, however, so their thoughts become increasingly preoccupied with death. Our attitude towards death is ambivalent: sometimes we shut it out and deny it, and sometimes we desperately want to talk about it and share our fears of the unknown. Preparing for Death • Kiibler-Ross (1969) uses the term anticipatory grief to describe how the terminally ill come to terms with their own understanding of imminent; death. One common feature of this is reminiscing. This may be a valuable way of 'sorting out' the past and present • This life review may result in a new sense of accomplishment, satisfaction and peace (and corresponds to Erikson's ego-integrity, • Coming to terms with our own death is a crucial task of life which Peck (1968) calls ego-transcendence versus ego-preoccupation. • We may review our lives privately (or internally) or we may share our memories and reflections with others. By helping us to organise a final perspective on our lives for ourselves, and leaving a record that will live on with others after we have died, sharing serves a double purpose Conclusions • A large number of marker events (or critical life events) or processes have been identified. • These include unemployment, retirement, marriage, divorce, parenthood and bereavement. • Psychological research has told us much about the effects of these and the ways in which they help us to understand adjustment to adulthood. Homework • Study Rogers Theory of Personality • You will research views and criticisms of this on the internet next week