Dramatic Monologue

advertisement

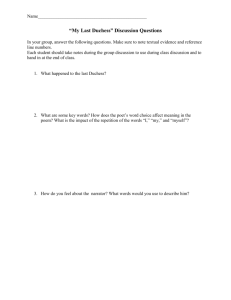

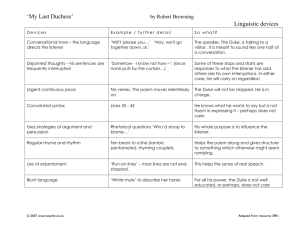

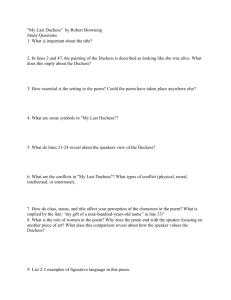

Dramatic Monologue: Love, Death and Ambition Lord Alfred Tennyson and Robert Browning Outline – Dramatic Monologue: Definition – “Ulysses” – Lord Alfred Tennyson – “My Last Duchess” – Robert Browning as a Victorian Poet Dramatic Monologue • A poem which involves a speaker speaking alone to a and an implied auditor. • Through his speech, the following is revealed: – what, when, where and how of “the story”; – “a gap between what that speaker says and what he or she actually reveals” (reference). Dramatic Monologue & the Reader • Browninesque dramatic monologue has three requirements: • The reader takes the part of the silent listener. • The speaker uses a case-making, argumentative tone. • We complete the dramatic scene from within, by means of inference and imagination. (Glenn Everett reference). Dramatic Monologue in Historical Context • The poets’ meeting the readers’ need for stories in Victorian society, when novel was a popular genre. • A device to explore the depth of human psychology and the theme of alienation– by assuming an personae (often quite alien to the poet’s own values and beliefs) • e.g. The Waste Land, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Ulysses Odysseus or Ulysses was a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the Odyssey. Ulysses Returns Chryseis to her Father 1648 (source) Ulysses 1. The who, where, when and why of the poem? The listener”s”? 2. Ulysses– What does he think about his present life (ll. 1-5), his past experience (ll. 7-21), and future goals (ll. 22-32). Are there contradictions in his selfperception? 3. Ulysses vs. Telemachus: "He works his work, I mine." Do you find Ulysses irresponsible or a-social? 4. a) blank verse -- rhythm (e.g. iambic pentameter), b) the arrangement of explosive and mellifluous sounds in the poem. Ulysses (1833) It little profits that an idle king, By this still hearth, among these barren crags, give out by measure Match'd with an aged wife, I mete and dole Unequal laws unto a savage race, That hoard, and sleep, and feed, and know not me. I cannot rest from travel; I will drink Life to the lees. All times I have enjoy'd Greatly, have suffer'd greatly, both with those Hyades = sisters, That loved me, and alone; on shore, and when The daughters of Atlas, Thro' scudding drifts the rainy Hyades who were turned into Vext the dim sea. I am become a name; a constellation of stars by Zeus. They vexed, For always roaming with a hungry heart or tormented, the sea Much have I seen and known,-- cities of men with blowing sheets of And manners, climates, councils, governments, rain ("scudding drifts"), Myself not least, but honor'd of them all,-just as the constellation can And drunk delight of battle with my peers, influence the sea and Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy. weather. Ulysses I am a part of all that I have met; Yet all experience is an arch wherethro' Gleams that untravell'd world whose margin fades For ever and for ever when I move. How dull it is to pause, to make an end, To rust unburnish'd, not to shine in use! As tho' to breathe were life! Life piled on life Were all too little, and of one to me Little remains; but every hour is saved From that eternal silence, something more, A bringer of new things; and vile it were For some three suns to store and hoard myself, And this gray spirit yearning in desire To follow knowledge like a sinking star, Beyond the utmost bound of human thought. unpolished Ulysses –Stanza 2 This is my son, mine own Telemachus, to whom I leave the sceptre and the isle,-Well-loved of me, discerning to fulfill This labor, by slow prudence to make mild A rugged people, and thro' soft degrees Subdue them to the useful and the good. Most blameless is he, centred in the sphere Of common duties, decent not to fail In offices of tenderness, and pay Meet adoration to my household gods, very proper When I am gone. He works his work, I mine. Ulysses –Stanza 3 There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail; There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners, Souls that have toil'd, and wrought, and thought with me,-That ever with a frolic welcome took The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed Free hearts, free foreheads,-- you and I are old; Old age hath yet his honor and his toil. Death closes all; but something ere the end, Some work of noble note, may yet be done, Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods. The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks; The long day wanes; the slow moon climbs; the deep Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends. 'T is not too late to seek a newer world. Ulysses –Stanza 3 Push off, and sitting well in order smite The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths Of all the western stars, until I die. It may be that the gulfs will wash us down; It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles, And see the great Achilles, whom we knew. Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho' We are not now that strength which in old days Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are,One equal temper of heroic hearts, Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. Ulysses: young and old 1. Ulysses at an old age—first speaking in his palace to no one (the wife does not seem to listen) and then ("There lies the port" ), to the mariners by the port. 2. Ulysses: a. present – a boring life in “barren crags” with an aged wife and tedious duties (mete and dole; not known); past: -- seen the world, well known, a lot of experience; change – action, to strive with god, to find something new. destiny – dark broad sea death (Happy isle=Elysium) Ulysses: ambition vs. duty Ulysses//mariners vs. his wife, people and Telemachus Is he irresponsible? (“hoard, and sleep, and feed”; “offices of tenderness”) 4. More question: Jerome H. Buckley asserts that the poem does not in fact convey • a will to go forward . . . but a determined retreat, a yearning, behind allegedly tired rhythms, to join the great Achilles (or possibly Arthur Hallam) in an Elysian retreat from life's vexations. [64] Do you agree? Ulysses with Three Desires—and three possible readings 1. 2. 3. Desire: for meaningful “living” but not mere breathing; an eventful life, but not dull routine; to “follow knowledge like a sinking star / Beyond the utmost bond of human thought”; for being a hero as he was before; --one "braving the struggle of life." Desire: to be a wanderer and break away from the status quo (now known, or "I am become a name“), in which he sees his wife ”aged,” his people “savage” (sleeping, eating and hoarding), and his son, Telemachus, who is “soft” (or "discerning," "prudent," "soft," "good," "blameless," "centered," and "tender“) --one dissatisfied with mundane life and thus irresponsible Desire: for “"There gloom the dark, broad seas" and the Happy Isle.” – one yearning for rest and death. Ulysses: Historical Contexts • In this poem Tennyson is elaborating upon a conviction he formed at his closest friend, Arthur Hallam's death "that life without faith leads to personal and social dislocation" (Chiasson 165). (source) • In Memoriam (1850) Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) As a “twilight poet” • Worried about poverty and contracting epilepsy (a family disease) a twilight poet • Deeply saddened by the death of his friend Hallam. (1833) • Shorted sighted and with keen interest in sound effects, he created his poems in his head, memorizing lines and then creating their contexts. • Many narrative poems about suspension and languidness; e.g. "The Lotos-Eaters" “Mariana” (a waiting woman); about dullness of immortality: dramatic monologue: "Tithonus.“ As a a poet Laureate (1850) • a philosopher-poet, dealing with contemporary concerns with science vs. God: ’Nature, Red in tooth and claw’ • a narrative poet catering to popular taste My Last Duchess (image) “My Last Duchess”: Starting Question 1. The "who, where, when, and why" of the poem? 2. The role the listener plays in this poem? 2. What is the last duchess like? (See ll. 2134) Why is she called the “last” duchess? Is she a flirt or one with genuine kindness to all creatures? 3. What is the duke's attitude to his duchess? What happened to her? 4. What kind of person is the duke? What does the ending reveal about him? “My Last Duchess” (1) Ferrara That's my last Duchess painted on the wall, Looking as if she were alive. I call That piece a wonder, now: Frà Pandolf's hands Worked busily a day, and there she stands. Will't please you sit and look at her? I said "Frà Pandolf" by design, for never read Strangers like you that pictured countenance, The depth and passion of its earnest glance, But to myself they turned (since none puts by The curtain I have drawn for you, but I) “My Last Duchess” (2) And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst, How such a glance came there; so, not the first Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, 'twas not Her husband's presence only, called that spot Of joy into the Duchess' cheek: perhaps Frà Pandolf chanced to say "Her mantle laps Over my Lady's wrist too much," or "Paint Must never hope to reproduce the faint Half-flush that dies along her throat": such stuff Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough “My Last Duchess” (3) For calling up that spot of joy. She had A heart -- how shall I say? -- too soon made glad, Too easily impressed; she liked whate'er She looked on, and her looks went everywhere. Sir, 'twas all one! My favour at her breast, The dropping of the daylight in the West, The bough of cherries some officious fool 過分殷勤 Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule She rode with round the terrace -- all and each Would draw from her alike the approving speech, “My Last Duchess” (4) Or blush, at least. She thanked men, -- good! but thanked Somehow -- I know not how -- as if she ranked My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name With anybody's gift. Who'd stoop to blame This sort of trifling? Even had you skill In speech -- (which I have not) -- to make your will Quite clear to such an one, and say, "Just this Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss, Or there exceed the mark" -- and if she let Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set “My Last Duchess” (5) indeed Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse, --E'en then would be some stooping, and I choose Never to stoop. Oh sir, she smiled, no doubt, Whene'er I passed her; but who passed without Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands; Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands As if alive. Will't please you rise? We'll meet The company below, then. I repeat, The Count your master's known munificence Is ample warrant that no just pretence Of mine for dowry will be disallowed; “My Last Duchess” (6) Though his fair daughter's self, as I avowed At starting, is my object. Nay, we'll go Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though, Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity, Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me! “My Last Duchess” 1. Time: the Italian Renaissance, when the duke is negotiating with an envoy over the dowry of his next marriage. 2. Place: the grand staircase in the ducal palace at Ferrara, in northern Italy 3. His purpose: to boast and/or to threaten. 4. silence of the listener = awe, alertness? “My Last Duchess” • • • • The duchess – jovial and loving equally to everyone and every being. last – 1) not late; she may be killed, but she may also be put in a convent. 2) will be another one. The duke: 1) possessive and arrogant, he treats the duchess and the next one as “objects” to possess; 2) proud—choose not to stoop His language: 1) implicit demand; 2) uses grand rhetoric to assert his power, disguising his lack of power. “My Last Duchess”— Dramatic Irony • Contradiction between what he says and what he means: – – – • • • double negative says he has no skills in speech says he refuses to stoop (Isn’t the command a compromise of his humanity?) Between assertion of power and powerlessness Power -- none but me draws the curtain Powerlessness– repetitions of “all” “not alone,” “it was all one.” Robert Browning (1812-1889) • Eloped with and married the poet Elizabeth Barrett (1806-1861, writer of Sonnets from the Portuguese), and settled with her in Florence. He produced comparatively little poetry during the next 15 years. • After Elizabeth Browning died in 1861, he returned to England. • DRAMATIS PERSONAE (1864) • THE RING AND THE BOOK (1869), based on the proceedings in a murder trial in Rome in 1698. (source) Reference • “Porphyria’s Lover”-visual presentation http://www.scottmccloud.com/c omics/porphyria/porphyria.html Teach & Learn • Explain one part of the poem • Give a question for discussion • Give one quiz question to test understanding • Within 10 mins • Test the other group in 10 mins • The last group in front of the whole class 10 mins • Group 1—Kate; group 2,3 David; group 4, 5 -- Daphne • By next Sunday – ppt and quiz