The American Revolution - vcehistory

advertisement

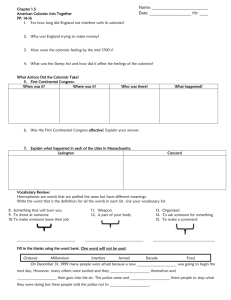

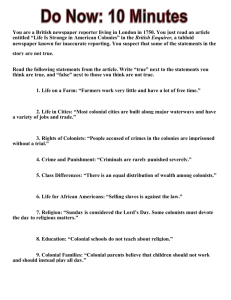

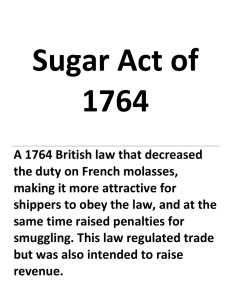

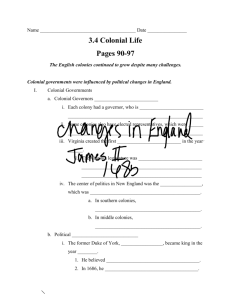

American Revolution Outcome 1 (America – 1763-1776) HTAV Student Lectures – 26 March 2012 Nick Frigo – Santa Maria College 1 Outcome 1 (America – 1763-1776) On completion of this unit the student should be able to evaluate the role of ideas, leaders, movements and events in the development of the revolution. • To achieve this outcome the student will draw on knowledge and related skills outlined in area of study 1. Key knowledge • the chronology of key events and factors which contributed to the revolution; • the causes of tensions and conflicts generated in the old regime that many historians see as contributing to the revolution; for example, colonial self assertion after the French and Indian War in the American colonies; • the ideas and ideologies utilised in revolutionary struggle; • the role of revolutionary individuals and groups in bringing about change; in the American colonies, Benjamin Franklin, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, Samuel Adams, Thomas Paine and the Sons of Liberty; 2 3 Legislation 4 5 Proclamation Act 1763 • • • • Reason for it? British Action Colonial Response? British Reaction? “. . . And we require all persons whatsoever, who have either wilfully or inadvertently seated themselves upon the lands . . . Above described . . . Forthwith to remove themselves from such settlements . . . and to the end that the Indians may be convinced of our justice . . . “ – Proclamation Act 1763. 6 April 1764 - Sugar Act • Factual Evidence Imposed duties on foreign sugar and and enforced customs duties. • Primary Source Evidence “but duties as high as are laid by this Act, cannot by any means . . . Be collected, being vastly greater than the trade itself can possibly bear . . . “ – Stephen Hopkins, Governor of Rhode Island. • Secondary Source Evidence “The Sugar Act (Grenville’s American revenue Act) was parliaments first law for the specific purpose of raising money in the colonies” • Reason – British Action – Colonial Reaction – British Response . . . 7 March 1765 -Stamp Act Factual Evidence Meant a tax on: legal documents, business contracts, licenses, land deeds, newspapers, journal and playing cards. • Primary Source Evidence How can it be reconciled that the “colonies, who are without one representative in the House of Commons, should be taxed by the British Parliament.” – James Otis, “The Rights of the British Colonists asserted and Proved”, July 1764 • Secondary Source Evidence “Through this Act, the British were taxing the colonial population to pay for the French war, in which colonists had suffered to expand the British Empire.” – Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the US., p. 61. ** Reason – British Action – Colonial Reaction – British Response . . . 8 Declaratory Act • Following the repeal of the Stamp Act, the Rockingham Ministry consented to the adoption of the Declaratory Act, “baldly stating that Parliament retained the power to legislate for the colonies ‘in all cases whatsoever’.” - Jack Rakove, Revolutionaries. • British parliament did not want to look like they were giving in to the colonists. • Parliament yielded to colonist protests, but WAS NOT prepared to exempt colonists from the highest power of the British Empire. 9 Townshend Acts • In January 1767, Charles Townshend, the chancellor of the exchequer, proposed levying duties on miscellaneous goods imported into the colonies – glass, lead, paint, paper, pasteboard, all items that Americans could not easily manufacture. 10 The Townshend Duties – Revenue Acts • Factual Evidence Taxed items that had to be imported: paint, tea, glass, paper - Colonists responded by attempted to lessen the use of such items (boycott). • Primary Source Evidence Contemporary Letter: “Another Act of Parliament which appears to me to be unconstitutional and as destructive to liberty of these colonies.” – Letters from a Farmer • Secondary Source Evidence • Reason – British Action – Colonial Reaction – British Response . . . 11 Townshend Acts • Townshend “clearly conceived his scheme as a way of habituating Americans to the payment of new taxes. He also hoped to exploit Franklin’s distinction between internal and external taxes, the former objectionable on constitutional grounds, the latter presumably acceptable under Parliament’s general authority over trade.” – Jack Rakove, Revolutionaries. 12 Intolerable (Coercive) Acts 1774 • This was a ‘punitive’ measure of the British Parliament in response to the Boston Tea Party. • The Boston Port Bill, effective 1 June 1774 prohibited loading or unloading of ships in Boston harbour until damages had been paid for the destroyed tea. – An exception of this was that military food, stores and fuel could be brought in (if cleared at Salem rather than Boston). 13 Intolerable (Coercive) Acts 1774 • The Administration of Justice Act, 20 May 1774 protected royal officials by providing that those accused of a capital crime committed in aiding the government would not be tried by the provincial court where the official was located, but would be tried in another colony or England. 14 Intolerable (Coercive) Acts 1774 • The Massachusetts Government Act, 20 May virtually annulled the colony’s charter, and gave the governor control over the town meeting. • At this time, Thomas Gage, commander in chief of the British Army in America, was made governor of the colony of Massachusetts. • Extensions to The Quartering and the Quebec Acts – not actually part of the ‘coercion’ but were considered so by the colonists. • The Quebec Act saw the British Parliament extend Canada’s boundaries to the Ohio River, cutting into territories claimed by the original 13 Colonies – colonists were NOT happy! 15 Intolerable (Coercive) Acts 1774 • The Intolerable Acts “rallied the other twelve colonies to the side of Massachusetts, produced the first Continental Congress and led to the Declaration of Independence” – Pollard, Factors in American History. 16 17 Colonial Action 18 The Stamp Act Congress • Gordon Wood claimed that while the formation of Stamp Act Congress was an “unprecedented display of colonial unity . . . With its opening acknowledgement of ‘all due subordination to that August Body the Parliament of Great Britain’, could not fully express American hostility.” – Gordon Wood, The American Revolution. • The Stamp Act Congress declarations defined the American position at the outset of the controversy, and despite subsequent confusion and stumbling, the colonists never abandoned this essential point. • The Declarations of the Stamp Act Congress, 1765 19 Stamp Act Congress • What the thirteen colonies did next was not really surprising: they sent representatives from their colonies to attend a meeting at the urging of James Otis. • After years of being oppressed and manned by the British crown, the Colonists felt that the time had come for them to fight back and claim what is rightly theirs: a land free of oppressors. • The twenty-seven representatives came from only nine colonies though; the other four were informed late but couldn’t reach the meeting in time. 20 Stamp Act Congress • The meeting paved the way to the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, which stated that there should be no taxes imposed on Colonists without their consent or receive a tax from a body which they have no representative in. • The Stamp Act is one of the main reasons why the Colonists even started to think of opposing the English crown at the first place. • In 1766, they repealed it and the Stamp Act Congress did a fairly good job. They removed a law that had been nothing but a burden to many Colonists, and did create a sense of unity amongst the thirteen colonies. • It was with the Stamp Act Congress that the thirteen colonies realized that much could be done if they worked together. 21 John Dickinson, Letters from a farmer in Pennsylvania • For Dickinson “a ‘tax was a tax’. Whatever its form, Parliament had no right to levy on the colonies . . . ‘Parliament … possesses a legal authority to regulate the trade of Great Britain, and all her colonies’, but it had no right to tax the colonies in any way”. – Edward Countryman, The American Revolution. 22 Townshend Act – Colonial Response • It took the colonists nearly two years to mount another effective boycott of British goods as an incentive for the repeal of the Townshend duties. • In December 1767, John Dickinson, published the first of twelve Letters from a farmer in Pennsylvania denouncing the new duties and other government money raising measures. • Dickinson wrote under a pseudonym but soon came to be known as the farmer. 23 1772 – The Committees of Correspondence. • Countryman states: “During the eight years that followed the Stamp Act, Britain tried again and again to make the colonies serve its interests. The result, however, was the opposite.” • Committees of Correspondence were created in 1772 to co-ordinate the activities of colonial agitators and to organise public opinion against the British Ministry. • The first committee was established in Boston on the idea of Samuel Adams. Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson led the movement for their establishment in Virginia. 24 1772 – The Committees of Correspondence. • According to Countryman, a gathering of farmers in Massachusetts met in their committees of correspondence and resolved in favour of “‘wise, prudent and spirited measures’” to keep the Intolerable Acts from going into effect. • From New York to the Carolinas, local communities established committees of correspondence to keep abreast of events. “Up and down the coast, people loaded vessels with supplies for the relief of the ‘poor of Boston’.” – Edward Countryman. • By 1774, colonials decided that they needed a Continental Congress to give direction to their movement. 25 Committees of Safety • These were first organised in 1775 – the first one in Massachusetts in February, made up of 11 men with the authority to mobilize militia and seize military stores. 26 The First Continental Congress • 56 delegates from 12 colonies met for the first time at Carpenter’s Hall, Philadelphia on 5 September 1774. • The decision was made that each delegate should have one vote. • In a set of declarations they denounced : – – – – – The Intolerable Acts The Quebec Act The extension of the Admiralty Courts The dissolution of colonial assemblies. The stationing of regular soldiers in colonial towns during peace time. 27 The First Continental Congress • Mercy Otis Warren wrote in her History: “All America . . . Waited in anxious hope and expectation the decisions of a continental congress”. • One of the most significant weaknesses the colonists faced on the outbreak of war was the lack of a centralised government. • While the 13 colonies had a long history of local government, they also had a history of jealousy . . . What problems might this present? • Some historians have been surprised by the ability to unite politically (given the previous problems they had). 28 The First Continental Congress • They declared 13 parliamentary Acts since 1763 as unconstitutional. • The delegates pledged to support economic sanctions until these Acts were repealed. • Ten resolutions set forth the rights of the colonists as they saw them. • They signed the Continental Association on 20 October 1774. • The congressmen agreed to reconvene on 10 May 1775 if their grievances were not heard. • They adjourned on 26 October 1774. 29 Suffolk Resolves • A product of the First Continental Congress they emerged on 17 September 1774. • They were drafted by Joseph Warren and adopted by a convention in Suffolk County, Massachusetts. • On the 9 September they were rushed to Philadelphia by Paul Revere. • The resolutions were presented by the radical delegates and endorsed by the First Continental Congress. • They: – declared the Intolerable (Coercive) Acts as unconstitutional – urged Massachusetts to form a government and withhold taxes from the Crown until the Acts were repealed. – advised the people to arm and recommended economic sanctions against British. 30 Galloway Plan • According to Gordon Wood, Joseph Galloway was the leader of the Pennsylvania Assembly. • He also stood as spokesman for the conservative congressional delegates from the middle colonies. • The Plan of Union that he proposed was presented on 28 September 1774. • An important feature of Galloway’s plan was that the colonial government, while inferior to that of Great Britain, would nevertheless have authority to regulate: – Commercial, civil, criminal, and police affairs when more than a single colony was involved. – The colonial government was to have veto power over all Parliamentary legislation affecting the colonies. 31 The Second Continental Congress • Met on 10 May 1775 at the State House (later Independence Hall) in Philadelphia. • The delegates resolve that the colonies be put in a state of military readiness (15 May). • 29 May – adopt an address to ask the Canadians to join the revolution. • Also included: raised riflemen, draft rules for the administration of the Congress, elect George Washing Commander in Chief . . . 32 The Second Continental Congress • The Battle of Bunker Hill took place on 17 June 1775 and on 5 July Congress adopted the “Olive Branch Petition” (drafted by John Dickinson). • On 10 June 1775, George III wrote to the Earl of Dartmouth that: “America must be a colony of England or treated as an enemy. Distant possessions standing upon an equality with the superior state is more ruinous than being deprived of such conventions.” 33 The Second Continental Congress • On 6 July 1775 the Congress adopts Dickenson’s “Declaration of the Causes and Necessities of Taking up Arms“ which explained and justified the creation of an army to fight a government which they still claimed allegiance to. • The various versions of this document, at least two, both argued that “although oppressive British actions had driven the American colonies into military action, reconciliation was still possible.” – Steven C. Bullock, The American Revolution. 34 Further colonial responses… • Dickinson’s ideas were not fully matched by the colonist’s action . . . • In 1765 the Stamp Act Congress had helped establish a framework for intercontinental unity. • In reality, the push for boycotts came from individual colonial assemblies . . . • “Shops selling British goods were smeared with the mixture of mud and faeces called ‘Hillsborough paint’ to mock the British minister for colonial affairs.” – Jack Rakove, Revolutionaries. 35