(2015). Performance and Challenges of Vegetable Market

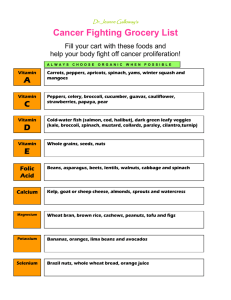

advertisement