Culture - Schulich School of Music

advertisement

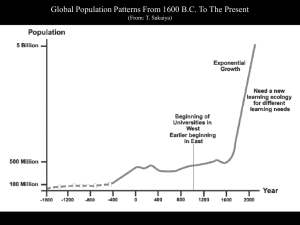

CASE STUDY: CULTURE February 27, 2014 Hugo Harmens, Jason Leung OVERVIEW: CHAPTERS 8–11 Culture in Songbirds and its Contribution to the Evolution of New Species When does Psychology Drive Culture? Olivier Morin Quantifying the Importance of Motifs on Attic Figure-Painted Pottery Darren E. Irwin Peter Schauer Agents, Intelligence, and Social Atoms Alex Bentley, Paul Ormerod 1 WHAT IS CULTURE? “The sum total of ways of living built up by a group of human beings and transmitted from one generation to another.” – Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary, second edition. 1999. Random House: New York. “The total set of beliefs, values, customs, and behavior patterns that characterizes a human population; the noninstinctive manner in which humans interact with or manipulate their environment.” – Academic Press Dictionary of Science and Technology. 1992. Academic Press: San Diego, California. “The customs, civilization, and achievements of a particular time or people.” – The Oxford Dictionary and Thesaurus, American Edition. 1996. Oxford University Press: New York. “The totality of socially transmitted behavior patterns, arts, beliefs, institutions, and all other products of human work and thought.” – www.thefreedictionary.com 2 WHAT IS CULTURE? Phenomenon originally conceived by humans to be unique to humans A desire to keep humans separate from other species? Problematic: Evidence of culture-like behaviour in animals Being species-specific can prevent us from making progress in understanding the origins and evolution of culture 3 WHAT IS CULTURE? What if we take out the words human or people? cd CULTURE: Socially learned behaviour that can grow and change through time ba 4 (Irwin 2013) GENES AND MEMES Question of Nature vs. Nurture Look to the natural world for clues Example: Birdsong Study of greenish warbler species Variation influenced by genes and learning Observations: Songs vary geographically Gradual differences in structure, syntax Female preference for complex songs 5 GENES AND MEMES Result: two non-interbreeding species in Siberia Different song structures, syntax Genetic pre-disposition to sing their species’ song structure Able to learn the other species’ song syntax WESTERN BRANCH: longer song units, but greater repetition EASTERN BRANCH: shorter song units, but greater repertoire 6 (Irwin 2013) GENE-CULTURE CO-EVOLUTION Sexual selection drives genes and memes to evolve Change in memes cause selection on genes Change in genes cause selection on memes 7 (Irwin 2013) GENE-CULTURE CO-EVOLUTION Culture is not simply that which is not genetic One system of GENE-CULTURE CO-EVOLUTION By studying such behaviour in animals, we can gain new insights to understanding of our own cultural phenomena 8 UNIVERSAL PSYCHOLOGICAL CONSTRAINTS Parallels in human cultures? Are there human species-wide cultural traits? Is culture the result of: Individuals? Society? [General psychological constraints] seem to influence culture in a way that is both uniform and weak. When one is in the business of explaining contrasts between individuals or societies, this makes them twice irrelevant. —Morin 2013 9 UNIVERSAL PSYCHOLOGICAL CONSTRAINTS Cultural Epidemiology: Culture… is a distribution of representations within a population. Being a statistical abstraction, this distribution lacks essence and causal powers. — Morin 2013 (emphasis added) Why? Allows for the study of transmission of culture CULTURAL TRANSMISSION CHAINS 10 CULTURAL TRANSMISSION CHAINS Long vs. Short: number of individuals involved Broad vs. Narrow: impact each individual has Through time or space Universal traits: cultural objects that persist in long and narrow chains 11 CULTURAL TRANSMISSION CHAINS Problem of scale Local impacts are also important to culture Cannot be ignored Not all cultural things come from long/narrow chains Culture is not a mere reflection of the human mind “Windows to the Human Mind”: Consistent and reliable indicators Underlying mental mechanisms 12 CULTURE AS A COLLECTIVE WHOLE So many people So many times and places When an idea travels through thousands of heads Millions of psychological filters Idiosyncrasies pull in all directions Central Limit Theorem Large sample size averaging effect Any remaining trend must be universal human trait Suggests statistical approach 13 CULTURE AS A COLLECTIVE WHOLE Immediate level: Numerical analysis can reveal hidden trends i.e., Trends not obvious in traditional approaches to cultural study Greek pottery and Quantification Peter Schauer (2013) 14 GREEK POTTERY AND QUANTIFICATION Through quantification: Assess existing scholarly claims about motif importance Make new observations of existing data Source material: Beazley archive 75,451 pieces between 650–300 BC Identified and catalogued manually by experts Preparing Beazley database for analysis 15 QUANTIFYING ART BOREAS motif clearly gains biggest share in the period 500–450 BC, when motifs already appearing in previous time-steps are omitted Not possible to support conclusion without prior knowledge PAN: increase in frequency supports Webster's correlation, but greatest frequency in PAN depictions occurred later 16 QUANTIFYING ART NIKE's peak 475–425 BC previously unnoted Warrants further investigation 17 (Schauer 2013) BENEFITS AND LIMITATIONS Cultural importance cannot be inferred from frequency alone Quantitative research can, in spite of this, show other tendencies Starting points for further research Perceived importance of works of art and individual artists Frequency revealing hidden cultural trends 18 LARGE-SCALE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR What if we pretend culture is just an emergent structure resulting from large-number statistics? Complex phenomena from simple rules Chess Fractals Differential equations DNA and amino acids Absence of (full) rationality (image from Planet3.org) 19 LARGE-SCALE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR Humans as Zero-Intelligence Particles We are not as smart as we think we are Also not independent/isolated Cannot make optimum or rational decisions We do not have access to all information Resources available Dimensions of human problems so large As if we had approximately zero intelligence 20 LARGE-SCALE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR Humans as Zero-Intelligence Particles Assume as little as possible To identify the most general characteristics of collective human behaviour Particles cannot: Act with purpose or intent Learn Adapt based on previous outcomes 21 (image from http://www.webgl.com/2012/02/webgl-demo-particles-morph/) LARGE-SCALE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR Adding intelligence Non-random interactions Networks Adding copying Trends and fashions Peer pressure Adding innovation 22 (image from http://www.webgl.com/2012/02/webgl-demo-particles-morph/) LARGE-SCALE HUMAN BEHAVIOUR Human decisions are social Despite grandiose claims of re-inventing social science (Barabási 2005), these models in physics often fail to capture essential elements of human behaviour. —Bentley and Ormerod 2013 23 THESIS 1: “BORROWING” By “borrowing” methods from different disciplines, we can build better models Statistical methods are the best models we have for studying large-scale phenomena Sophisticated means of dealing with complexity and heterogeneity No need to resort to simplified assumptions of equilibrium or optimality View of large-scale emergent effects (social physics) through individual-scale behaviour (anthropology) Insights into “tipping points” resulting from nondescript individual interactions 24 THESIS 1: “BORROWING” By “borrowing” methods from different disciplines, we can build better models Models are improved by using more data points Everyday and unexceptional works are more numerous and, hence, more representative Study of culture as a collective WHOLE rather than an isolated individual Influences on/of artists can be clearer 25 THESIS 2: “MIXING” By “mixing” knowledge from different disciplines, all will benefit Disciplines will often encounter topics outside their traditionally-defined limits Collaboration will broaden applicability across multiple diverse disciplines 26 THESIS 2: “MIXING” By “mixing” knowledge from different disciplines, all will benefit Offer new non-biased perspectives Example: Physics and Anthropology Physics: Can characterize a certain category of collective behaviour But flawed assumptions about human behaviour Anthropology: Has a deep record of individual behaviour and its infinite variability But may not see collective effects 27 TOWARDS CONSILIENCE 28 PURITY On the other hand, physicists like to say physics is to math as sex is to masturbation. 29 xkcd by Randall Munroe, http://xkcd.com/435/ THE “SPECIAL” HUMANS Science is breaking down ways in which we had previously thought we were “special” Are we afraid our discipline(s) may also not be “special”? PURITY vs. conceptual blending (consilience) as inherently human PURITY vs. POLLUTION 30 THE “SPECIAL” HUMANS AND PURITY “Core disgust” Humanities towards Sciences? Sciences towards Humanities? Objectivist approach without losing our achievements Do the humanists see the scientists’ striving for “God’s eye view” inherently distorting and wrong? 31 TOWARDS CONSILIENCE Is consilience a question of philosophy? Do philosophical questions matter? “What is Truth?” Objectivism, post-modernism (v2.0) Vast majority of fields operate independent of such questions Anthropology, history, music, social science… Biology, engineering, meteorology, pharmacology… Why is there resistance? 32 TOWARDS CONSILIENCE Fear of deprecation of one’s own discipline? Fear of unknowns outside one’s own discipline? Fear of untried methods? Purity of disciplines False belief statistical models ignore the x% minority Fear of results? Zero-intelligence – we are not so smart after all Nor are we “special” 33 TOWARDS CONSILIENCE 34 TOWARDS CONSILIENCE How? New attitudes toward education Current system designed in/for Industrial Age Practicality Assembly line Committee of Ten, 1892 35 Angus, D., and J. Mirel. 1999. The Failed Promise of the American High School, 1890–1995. New York: Teachers College Press. ISBN 0807738425. TOWARDS CONSILIENCE Current focus on STEM subjects Why ingrain a divide between humanities and sciences? Could the desire to dichotomize knowledge be a kink in our cultural transmission chain? 36 TOWARDS CONSILIENCE The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks Rebecca Skloot, 2010 English Biology (HeLa cells) History (Civil Rights Movement) Ethics (issues of race and class) Complete integration of Knowledge (practical issues aside) New Renaissance of Knowledge But more importantly… 37 RECONCILIATION 38