Donne and Rochester - utk-ma-comp

advertisement

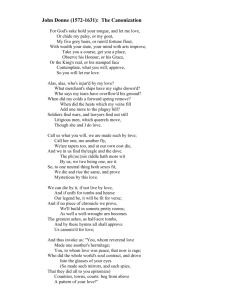

Literary Shenanigans: John Donne and John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester John Donne (1572-1631) “The first thing to remember about Donne is that he was a Catholic; the second, that he betrayed his faith” (Carey 15) “Some of [Donne’s] most persistent imaginative habits may be traced to this impatience with a fragmented state of being. It made him hungry for absolutes and totalities…The more fluid and multifarious your mind, the harder it is to feel sure you exist as a definable self. Donne seemed to be disturbed, or at least intrigued, but this sense of absence quite early in life, and to have contemplated the steps he might take to counteract it” (Carey 169) Brief Biography 1572, born into a Catholic family; mother’s side related to Thomas More, father dies when John is four-years-old 1583-1584, Uncle Jasper Heywood, head of a Jesuit mission, captured, imprisoned, and executed 1592-1593, begins studying law at Thavies Inn then transfers to Lincoln’s Inn; Satires and Songs and Sonnets believed to be written sometime during this stay in London 1593, brother Henry dies of plague while imprisoned for harboring a Catholic priest 1597, begins work as secretary for Sir Thomas Egerton 1601-1602, Donne secretly marries Egerton’s niece, Ann More; is briefly imprisoned after being released from Egerton’s service 1607, Divine Poems thought to be published 1608, amidst poverty and the loss of four of his twelve children, Donne writes Biathanatos, a justification of suicide 1609-1610, when Holy Sonnets were written 1611, publishes The First Anniversary to commemorate Elizabeth Drury, daughter of his patron 1615, ordained deacon and priest 1621, elected Dean of St. Paul’s 1624, Devotions upon Emergent Occasions published 1631, Donne dies after obsessing over a sketch of himself tightly wrapped, facing the East; it is his “hourly object till his death” (Walton 113) Donne as a Metaphysical Poet Donne is often thought to be the face of the metaphysical poets of the 17th century, though he is the most unique, in method and form, of the group. According to Helen Gardner, metaphysical poets are characterized by 1) concentration, or the demand for attention, as seen through the poems’ brevity and simple, but variable verse form as to compress the poem; and 2) “fondness for conceits…a comparison whose ingenuity is more striking than its justness” (19) This style of poetry, particularly pertaining to Donne’s, was not well received until the 20 th century. Furthering Dryden’s quote, “He affects the metaphysics...perplexes the minds of the fair sex with nice speculations of philosophy, when he should engage their hearts and entertain them with the softness of love,”(Gardner 15) Samuel Johnson coined the term “metaphysical poet” in his Life of Cowley, saying himself, “Heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together.” Ben Jonson, a metaphysical poet himself, claimed Donne’s best poetry was written at age 25, however, his lack of form would make him be forgotten. Donne was revived with the 20th-century modernists, particularly through T.S. Eliot and the critic F.R. Leavis. Eliot said that Donne was the last great writer of the English tradition with a dissatisfaction of English civility; his poems possessed an immediacy of thought. Leavis claimed, “At last we read as we read the living.” Other metaphysical poets include: George Herbert, Thomas Carew, and Andrew Marvell amongst others. Songs and Sonnets Ironically only contains one formal sonnet. The collection was not consolidated and published until the 1630s and was assumed to have been written before his ordainment and marriage, during a time of more rakish behavior and religious uncertainty. Donne fully embraced his place as a post-Petrarchan, experimenting with form and style. Christopher Warley claims, “Donne stands for an association of sensibility in his own time against the ‘mass production’ of the Elizabethans—the merely fashionable, merely transitory, ‘vogue’ for sonneteering” (37). Thematically, Donne still explores the Petrarchan notion of love, but he does so with a power, or as Carey believes, a “dictatorial attitude… [that violently combines] objects of the sensed world in his imagery” (117). Suggested poems: “The Canonization,” “The Sun Rising,” “The Flea,” “A Valediction: forbidding Mourning,” and “The Ecstasty. The Holy Sonnets Probably written between 1609 and 1610, Donne’s life at this point was plagued by death and religious (and existential) uncertainty. The Holy Sonnets are concerned with Hell and Donne’s fear that he is not worth of redemption. Though still metaphysical with his conceits, the adoption of the strict sonnet form demonstrates somewhat of an inversion from Songs and Sonnets. Gary Kuchar claims, “The fundamental drama of the Holy Sonnets is characterized by the speaker’s terrifying recognition that repentance requires him to experience his lack of autonomy—to undergo a physically violent process in which he comes to realize…that in himself he is nothing” (537). Whereas Donne wanted ownership of his mistresses in Songs and Sonnets, he almost masochistically demands God to control and ravage him in the Holy Sonnets. Suggested poems (because the numbering is different from volume to volume, I will go by the first words of the poem): “Batter my heart,” “Oh my black soul!,” The First Anniversary and Devotions upon Emergent Occasions The First Anniversary was written upon the death of Elizabeth Drury, the daughter of his patron Sir Robert Drury, in 1611. Because Sir Robert Drury was his patron, and Donne never actually met Elizabeth, many have cast this poem aside as insincere and self-serving. The First Anniversary is “divided an introduction, a conclusion, and five distinct sections which form the body of the work. Each of these sections is subdivided into three sections: first, a meditation on some aspect of ‘the frailty and the decay of this whole world;’ second, a eulogy of Elizabeth Drury as the ‘Idea’ of human perfection and the source of hope, now lost, for the world; third, a refrain introducing a moral” (Martz 2). Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, published in 1624, studies Donne’s illness (probably typhus) in its developing stages through 23 devotions, each broken up into three parts: a meditation, an expostulation, and a prayer. He investigates the relationship between his body and soul, paralleling his physical sickness to the inherent sin within him. John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester (1647-1680) “None of all our libertines understood better than he the secret mysteries of sin, [he] had studied everything that could support a man in it” (Bishop Burnet 84) “Knowledge and power became most dangerous…[they] seemed to affect something singular and paradoxical in his impieties, as well as in his writings, above the reach of thought of other men” (Reverend Parsons 12). Brief Biography 1647, born to Henry, a Royalist under Charles I whom John never got to know, and Anne, of a prominent Puritan family, shrewd and sober 1659-1660, educated at Oxford under Robert Whitehall who was said to plant the seed of the libertine in young John 1661, granted monetary allowance by Charles II (because of his father Henry’s loyalty) and sent on Grand Tour 1665, attempts to abduct Elizabeth Malet, whose family disapproved of their marriage because of John’s financial situation. He was subsequently, and briefly, imprisoned, yet he eventually married Elizabeth in 1667. Despite his libertine life, the two were said to be happily married. 1674-1675, the period in which he writes his best poetry, during which he writes “A Satyr against Reason and Mankind” and, according to Bishop Burnet, was continually drunk 1675-1677, reportedly trains and has an illegitimate child with the subsequently famous actress Elizabeth Barry 1676, the beginning of his downfall after he nearly beats a constable to death after being denied a whore he thought to be in his house; forced into hiding 1676-1680, falls into illness and depression (probably syphilis, among other things). In 1679 until his death, Bishop Burnet holds dialogue with him at his deathbed at which, according to Burnet, Rochester converted to Christianity. It was this account, not his poetry, that made Rochester famous with the contemporary audience. “A Satyr against Reason and Mankind” The most famous of his poems, written in two parts, this offers a microcosm of his poetry and life, demonstrating his “Skepticism” philosophy, his libertine lifestyle, his sharp wit, and a longing (though not a belief in) for absolutes and good in the world. The first of the two portions represents the more common perception of Rochester. Here he postulates the superiority of the tangible and real “That reason which distinguishes by sense” (line 100), over the ideal of a reason based upon fear and arbitrary order. The tone with which Rochester writes this first portion reflects the skeptic, libertine side of him in its freedom, sharpness, and irony. Senses should dictate understanding, but not on the abstract level: “Thus, sir, you see what human nature craves,/Most men are cowards, all men should be knaves” (lines 168169). The second portion (or addition) beginning at line 174, was more than likely a response to a Stillingfleet sermon in which he criticizes the libertines and their arrogant and false sense of confidence. The tone of the “Addition” differs from that of the original portion of “Satyr”. Where Rochester writes with a more assured, comedic, and ironic style in the first part, he now finishes with a vulnerability and desperate request (that he knows cannot be satisfied) for a good man, humble, just, and chaste. The two portions of the poem disparage one another. The man of the first portion is of “that sensual tribe, whose talents lie/ In avarice, pride, sloth, and gluttony” (lines 202-203) that the man of the second portion despises. Yet the man of the second portion, a man whose “wisdom did happiness destroy” (line 33), is one that the rake of the first portion would hate. Griffin claims that, “The ‘Satyr’ as a whole, then, is a demonstrably ambiguous poem, stylistically and thematically. Although we may extract from one part of the poem a sensationalist ethic, in other parts we find that such an ethic does not produce good or happy men…[he is] a man for whom an unbridgeable gap existed between the ideal and the realizable, both in his own experience and in his poems.” (243-244) Suggested poems: “The Fall,” “The Disabled Debauchee,” “Upon Nothing,” “To the Postboy,” “A Satyr on Charles II,” and “Signor Dildo.” Donne Sources Carey, John. John Donne: Life, Mind and Art. New York: Oxford UP, 1981. Print. Donne, John. John Donne: Selected Poetry. Ed. John Carey. New York: Oxford UP, 1996. Print. Gross, Kenneth. "John Donne's Lyric Skepticism: In a Strange Way." Modern Philology: A Journal Devoted to Research in Medieval and Modern Literature 101.3 (2004): 371-99. Print. Guss, Donald L. John Donne, Petrarchist. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 1966. Print. Kuchar, Gary. "Petrarchism and Repentance in John Donne's Holy Sonnets." Modern Philology: Critical and Historical Studies in Literature, Medieval Through Contemporary 105.3 (2008): 535-69. Print. Martz, Louis L. John Donne in Meditation: The Anniversaries. New York: Haskell House Publishers, 1970. Print. Oliver, P. M. Donne's Religious Writing: A Discourse of Feigned Devotion. New York: Longman, 1997. Print. Spiller, Michael. Early Modern Sonneteers: From Wyatt to Milton. Horndon: Northcote House, 2001. Print. Walton, Izaak. "The life of John Donne, Dr. in divinity, and late dean of Saint Pauls Church." EEBO. ProQuest LLC. Web. 24 Nov. 2009. Warley, Christopher. Sonnet Sequences and Social Distinction in Renaissance England. New York: Cambridge UP, 2005. Print. Rochester Sources Burnet, Gilbert. "Some passages in the life and death of John Earl of Rochester, written by Gilbert Burnet, ... With a sermon, preached at the funeral of the said ..." Ed. Samuel Johnson. ECCO. Gale Cenage Learning, 01 Nov. 2004. Web. 11 Oct. 2009. Fisher, Nicholas. "The Contemporary Reception of Rochester's "A Satyr Against Mankind"" The Review of English Studies 57.229 (2006): 185-220. Print. Griffin, Dustin H. Satires Against Man: The Poems of Rochester. Berkley: University of California, 1973. Print. Johnson, James William. A Profane Wit: The Life of John WIlmot, Earl of Rochester. Rochester: The University of Rochester, 2004. Print. Parsons, Robert. "Sermon Preach'd at the Funeral of the Right Honourable John Earl of Rochester." ECCO. Gale Cenage Learning, 01 Nov. 2004. Web. 07 Nov. 2009. Stillingfleet, Edward. "Fifty sermons preached upon several occasions. By the Right Reverend Father in God, Edward Stillingfleet, ..." ECCO. Gale Cenage Learning, 01 Nov. 2004. Web. 27 Nov. 2009. The Libertine. Dir. Stephen Jeffries. Perf. Johnny Depp and John Malkovich. The Weinstein Company, 2005. DVD. Thormahalen, Marianne. "Rochester and the Fall: The Roots of Discontent." A Journal of English Language and Literature 32.1 (1988): 369-409. Print. Vieth, David M., ed. The Complete Poems of John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester. New Haven: Yale UP, 1968. Print. Wilcoxon, Reba. "Rochester's Philosophical Premises: A Case for Consistency." Eighteenth-Century Studies 8.2 (1974-1975): 183-201. Print.