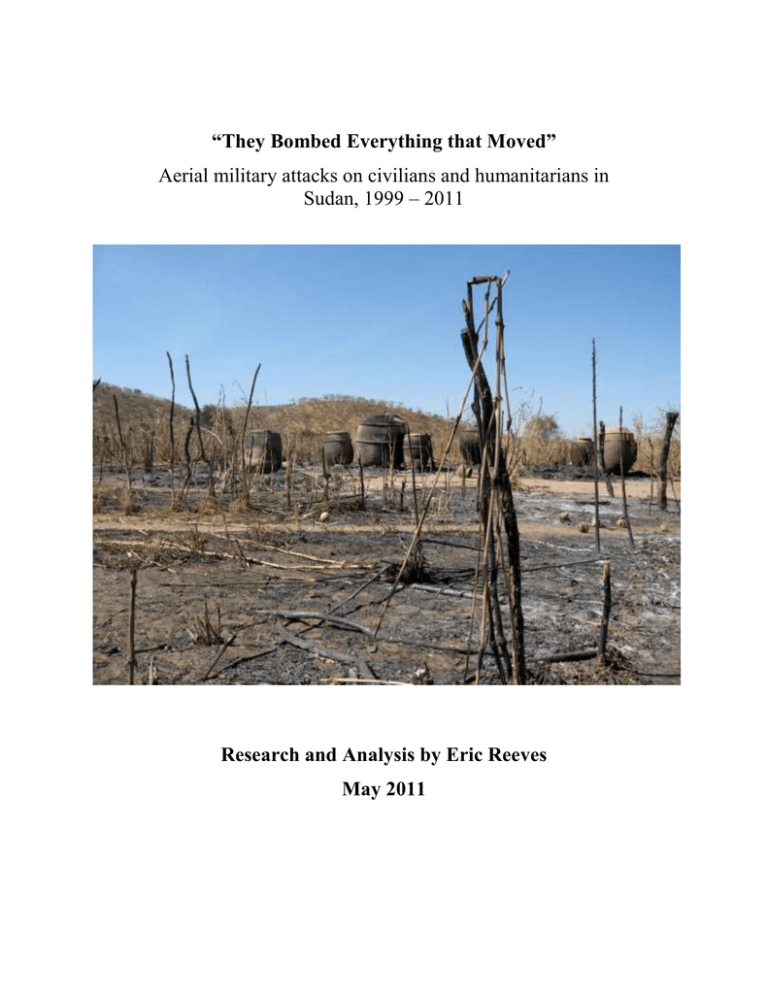

4 days of airstrikes causes at least 1

advertisement