Why do we have to annotate, take notes, and think?

advertisement

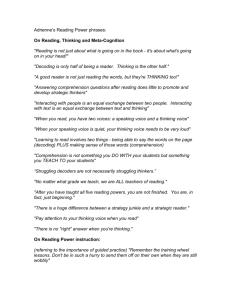

Why do we have to annotate, take notes, and keep a journal? Do you write in books? Why or why not? According to NY Times Writer Sam Anderson…. One day in college I was trawling the library for a good book to read when I found a book called “How to Read a Book.” I tried to read it, but must have been doing something wrong, because it struck me as oldfashioned and dull, and I could get through only a tiny chunk of it. That chunk, however, contained a statement that changed my reading life forever. The author argued that you didn’t truly own a book (spiritually, intellectually) until you had marked it up. Marginalia Why Annotate? Annotate any text that you must know well, in detail, and from which you might need to produce evidence that supports your knowledge or reading, such as a book on which you will be tested. What the reader gets from annotating is a deeper initial reading and an understanding of the text that lasts. You can deliberately engage the author in conversation and questions, maybe stopping to argue, pay a compliment, or clarify an important issue—much like having a teacher or storyteller with you in the room. If and when you come back to the book, that initial interchange is recorded for you, making an excellent and entirely personal study tool. Why take notes? Your quickwrites/ journal Quickwrites & Journals are places To think To generate To open up To break down, work through A place to wonder, experiment, try ideas out To reflect and respond Your quickwrites/journal activities Will be assigned points that are part of your participation grade (25% category; 2X a quarter) will introduce major units/works or reflect on what we’re currently reading in an effort to make the literature more personal and relevant major paper every semester May develop into major writing grades (50% category) need to be dated and labelled/titled Must be kept in the writing section of your notebooks, and therefore will be part of your notebook grade as well Must be thoughtful, reflective, legible Who do you think owned this book of notes? Whose journal is this? Whose Private Idea book is this? Leonardo DaVinci Mark Twain Charlotte Bronte, 1836 Now, let’s revisit that “quiz” 1. I have to read every word and look up the ones I don’t know. False! If you stop and look up every word, it’ll take forever, so use your context clues BUT there are still times to add to your literary vocabulary Focus on important phrases and try to identify main ideas and plot the FIRST time you read, implying that you’ll read more than once. 2. Reading once is enough False! We just answered that on the previous slide! Hint: you don’t have to read and annotate all at the same time. Read once for comprehension and then write a brief summary. Then go back and look for patterns, the significance of literary elements, characterization and stuff like that. You’ll get a handout later (today?) with strategies. 3. You are not allowed to skip or skim passages in reading False! Tho’ you should skim rather than skip. It really depends on what you’re reading. If it’s Robinson Crusoe and he’s listing in great detail how exactly he built some contraption to help him survive, and it goes on for 3 pages, you are totally allowed to skim. If you’re reading an informational text or article, not so much. If you’re reading Tolkien’s Fellowship of the Rings, and Tom Bombadil’s songs are driving you crazy, then perhaps skip for now… 4. If you read too rapidly, your comprehension will drop. False! Research shows that there is little relation between rate and comprehension; some students read rapidly and comprehend well, others read slowly and comprehend poorly. Whether you have good comprehension depends on whether you can extract and retain the important ideas from your reading, not on how fast you read. SO you can train yourself to do this efficiently, especially in classes that have lots of reading. If you concentrate on your purpose for reading (locating main ideas and details, and forcing yourself to stick to the task of finding them quickly), both your speed and comprehension could increase. Concern yourself with not how fast you can get through a chapter, but with how quickly you can locate the facts and ideas that you need. 5. I don’t need to write notes in the margins as long as I underline, circle, and/or highlight. False on SO many levels. This is why we are teaching you strategies about what and how to do this. 6. If I become an effective annotator and active reader, I will be better able to predict the endings of movies and books. TRUE! At least, it works for me, much to the annoyance of anyone’s who has ever watched a movie with me. What this question is really addressing is the ability to look for patterns, make connections, and become an active reader because you’re examining and thinking about what you’re reading. And once you can do that, certain details will form into recognizable patterns, and you’ll be like, “Hey, why did that character do that? Wait a minute…he wouldn’t do that unless there was a reason for it.” Think Chekov’s gun. Or “save the cat.” . Now let’s grab a couple of handouts.