Work Cited Page - Purdue University Calumet

advertisement

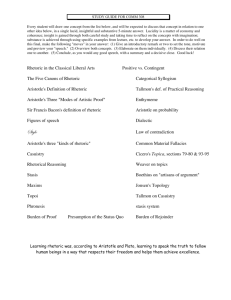

Script Music Digital Rhetoric: Understanding and creating logos, ethos, and pathos through multimodal texts. Digital Rhetoric can be confusing. But so is today’s informational world. To begin, I will discuss this topic by first defining rhetoric in the classical sense, then I will relate the classical definition with the modern and digital definition and hopefully explain how it is used in the multi modal context. Over 2000 years ago, Aristotle in book I of Rhetorica defined rhetoric as “the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion” (Aristotle). In understanding rhetoric and its different ways of persuasion, “we look upon the power of observing the means of persuasion on almost any subject presented to us” (Aristotle). So in a sense, rhetoric concerns both observing and persuading: it is about viewing arguments as well as understanding how arguments are used. In dealing with rhetoric, Aristotle describes three kinds of tools or techniques used in order to be persuasive: Ethos, pathos, and logos. Ethos depends on the “personal character of the speaker,” where it “should be [based] by what the speaker says” (Aristotle). Ethos is important “character [is] the most effective means of persuasion [one can] posse[]” (Aristotle). The character of the speaker—or the one doing the persuading—must first convince an audience that he/she is not only knowledgeable of the subject, but trustworthy and likeable as well. Since there are many different ways to present oneself as knowledgeable, the person doing the persuading must understand what his or her audience considers trustworthy and dependable. In other words, different audiences might disagree on what is trustworthy or not. Moving on. Pathos is defined as “putting the audience into a certain frame of mind.” It can occur when “the speech stirs emotions” (Aristotle). It is used to bring the audience into a particular emotional state. Aristotle mentions: “Our judgments when we are pleased and friendly are not the same as when we are pained and hostile” (Aristotle). This may seem obvious, but appealing to emotions is crucial in attempting to persuade someone of something. The best emotional appeals hypnotize the audience into believing in the most grandiose beliefs. Logos is, on the other hand, a little trickier. Defined literary as “speech itself,” logos is “when...a truth, or an apparent truth, is proven by means of the persuasive arguments suitable to the case in question.” Logos is reason. The key word is “proved” because one must logically prove something in order to persuade an audience. If the conclusion does not fit with the rest of the premises, then the speaker is lacking logos and more than likely not to persuade the audience. Now that we have a definition of classical rhetoric, what is digital rhetoric? Well, it is quite simple in a sense. It is taking the same definitions from thousands of years ago and applying it to today’s technological world. All in all, digital rhetoric has to deal observation and persuasion in various digital formats. These new forms are much different from the speeches and orations in Aristotle’s day. In today’s world it is not so much about speech anymore as it is about many different forms of discourse. On her website titled Digital Rhetoric Professor Elizabeth Losh elaborates: “Digital rhetoric is characterized by many new genres: e-mail, electronic slides, webpages, blogs, wikis, [and] video games” (Losh). These new forms of discourse are used as tools by various people to persuade on a daily basis. Losh further elaborates on the importance of understanding how these digital tools are used rhetorically: “Given the importance of digital rhetoric in the academy, government, and contemporary workplaces, the consequences of incomplete digital literacy can be serious. Those who never adequately acquire electronic competence now pay the price in wealth, professional success, social capital, and civic input” (Losh). In other words, those who are unable to understand digital rhetoric will be at a disadvantage because they will not be able to understand these discourses that seek to persuade them. She further elaborates: “Our very ability to compete economically and co-exist politically in the face of globalization may depend on bridging a "Digital Divide" between what Manuel Castells has called the "interacting" and the "interacted" (Losh). In other words, it is more crucial than ever to understand how digital rhetoric performs in everyday life. Rhetoric—ethos, pathos and logos—is no longer observed through speech or human interaction. It is now through images, hyper-links, power-points, websites, etc” (Losh). Lastly, Losh explains digital rhetoric is defined by Elizabeth Losh using four ways: 1) “The rhetorical conventions of new digital genres in everyday discourse;” (Losh) An example of this would be how emails persuade. Things like junk mail and spam come to mind, but also less obvious example like email subscription, and email etiquette are also persuasive in and of themselves. 2) “Public rhetoric via electronic distributed networks or hypertext; 3) Scholarly methods of interpretation for the critical analysis of new media;” (Losh) In this case, understanding rhetorical theory and rhetorical analysis interprets and analyses different digital discourses. 4) The verbal and visual culture of information (as opposed to knowledge) (Losh). This last case deal particularly with how information is used and disseminated. It is not about seeing how knowledge functions in today’s society, but the ways in which discourses seek to persuade. Work Cited Page Aristotle, “Rhetoric.” Translated by W. Rhys Roberts. eBooks@Adelaide.The University of Adelaide Library. South Australia. 10 Nov 2010. Web. Http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/a/aristotle/a8rh/book1.html Losh, Elizabeth. “Digital Rhetoric” Genres, Disciplines, and Trends. University of California, Irving. Web. Accessed on 10 Nov 2010. http://www.digitalrhetoric.org/