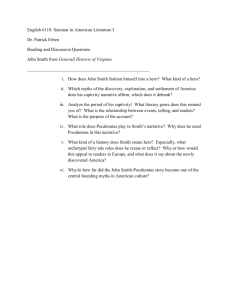

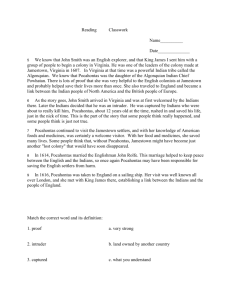

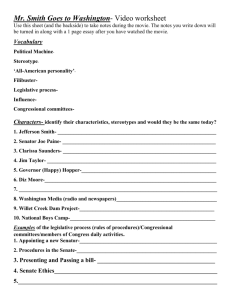

“History of the US in 20 Movies” – First Section

advertisement