Agenda - Rebel Rule

advertisement

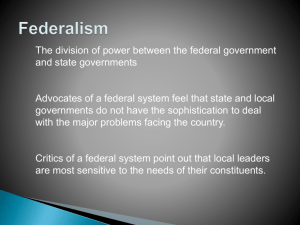

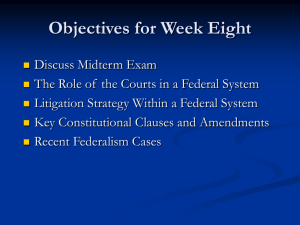

AP Government 2015-2016 Unit 3: Federalism Lesson 3 I. Introduction A. Objective: Establishing Supremacy B. Do Now: What is the Supremacy Clause? Where is the Supremacy Clause? Why is it important? II. Supreme A. According to the Constitution B. Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1816) Facts of the Case: Lord Fairfax held land in Virginia. He was a Loyalist and fled to England during the Revolution. He died in 1781 and left the land to his nephew, Denny Martin, who was a British subject. The following year, the Virginia legislature voided the original land grant and transferred the land back to Virginia. Virginia granted a portion of this land to David Hunter. The Jay Treaty seemed to make clear that Lord Fairfax was entitled to the property. The Supreme Court declared that Fairfax was so entitled, but the Virginia courts, where the suit arose, refused to allow the Supreme Court’s decision. Question: Does the appellate power of the Supreme Court extend to the Virginia courts? Decision: Bottom Line: III. Implied Powers A. Definition Federalist No.33 (Hamilton): “It is EXPRESSLY to execute these powers (Article I Section 8) that the sweeping clause, as it has been affectedly called, authorizes the national legislature to pass all NECESSARY and PROPER laws. IF there is anything exceptionable, it must be sought for in the specific powers upon which this general declaration is predicated… The propriety of a law, in a constitutional light, must always be determined by the nature of the powers upon which it is founded.” (1) What does Hamilton refer to as the “sweeping clause”? (2) How does Hamilton say the necessity and propriety of a law should be judged? Anti-Federalist No.1 (“Brutus”): “The powers given by this article are very general and comprehensive, and it may receive a construction to justify the passing almost any law. A power to make all laws, which shall be necessary and proper, for carrying into execution, all powers vested by the constitution in the government of the United States, or any department or officer thereof, is a power very comprehensive…” (1) What warning does Brutus make about the Necessary and Proper Clause? B. McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) Facts of the Case: After a first attempt in 1791, Congress established the Second Bank of the United States in 1816. Many states opposed branches of the National Bank within their borders. They did not want the National Bank competing with their own banks and objected to the establishment of a National Bank as an unconstitutional exercise of Congress’ power. In 1818, the state of Maryland passed legislation to impose taxes on the bank of $15,000 a year. James McCulloch, the cashier of the Baltimore branch of the bank, refused to pay the tax. The case went to the Supreme Court. Maryland argued that as a sovereign state, it had the power AP Government 2015-2016 to tax any business within its border. McCulloch’s attorneys argued that a national bank was “necessary and proper” for Congress to establish in order to carry out its enumerated powers. Questions: a. Did Congress have the authority to establish the bank? b. Did Maryland law unconstitutionally interfere with congressional power? Decision: Bottom Line: IV. Commerce Power A. Definition B. Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) Facts of the Case: The state of New York gave Aaron Ogden an exclusive license to operate steamboat ferries between New Jersey and New York City on the Hudson River. Thomas Gibson, another steamboat operator, ran two ferries along the same route with a license from the national government. Ogden sought an injunction against Gibbons in New York state court, claiming that the state had given him exclusive rights to operate the route. In response, Gibbons claimed he had the right to operate on the route pursuant to a 1793 act of Congress regulating coastal commerce. The New York court found for Ogden and ordered Gibbons to cease operating his steamships. On appeal, the New York court affirmed the order. Gibbons appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reviewed the case in 1824. Question: Did the state of New York exercise authority in a realm reserved exclusively to Congress, namely, the regulation of interstate commerce? Decision: Bottom Line: C. Lochner v. New York (1905) Facts of the Case: In 1895, the New York legislature unanimously enacted the Bakeshop Act, which regulated sanitary conditions in bakeries and also prohibited individuals from working in bakeries for more than ten hours per day or sixty hours per week. It was, in essence, a “labor law.” There is historical evidence that long-established baking companies in new York had formed an explicitly racist union and were attempting to shut off competition from new immigrant bakers who were willing to work long hours. Joseph Lochner, who owned Lochner’s Home Bakery in Utica, was fined $50 for allowing an employee to work more than 60 hours a week. Lochner was sentenced to incarceration in a county jail until he paid the fine, or, if he didn’t pay, for 50 days. Lochner appealed his conviction up to the New York Court of Appeals (New York State’s highest court), which affirmed his sentence. Lochner’s appeal was based on the 14th Amendment which provides “…nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Lochner argued that the right to freely contract was one of the rights encompassed by due process – based on Lockean Provisos, which typically said, “All men are by nature free and independent, and have certain inalienable rights, among which are those of enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring and possessing and protecting property; and pursuing and obtaining safety and happiness.” We have right over our own actions. The state argued that such laws are for the purpose of preserving public health, safety, or morals, which is the state’s power. Question: Does the New York law violate the liberty protected by due process of the 14th Amendment? AP Government 2015-2016 Decision: Bottom Line: D. Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918) Facts of the Case: Around the turn of the 20th century in the U.S., it was not uncommon for children to work long hours in factories, mills, and other industrial settings. Many families depended on the income earned by their children. Public concern about the effect this kind of work had on children began to rise. Advocates for child labor laws pointed out that children who worked such long hours (sometimes as much as 60 or 70 hours a week) were deprived of education, fresh air, and time to play. They also worried about the physical risks: children in factories had high accident rates. Some states passed laws restricting child labor, but these placed states with restrictions at an economic disadvantage. In response to these concerns, Congress passed the Keating-Owen Act of 1916. This law forbade the shipment across state lines of goods made in factories which employed children under the age of 14, or children between 14 and 16 who worked more than 8 hours a day, overnight, or more than 6 days a week. Congress claimed constitutional authority for this law because Article I Section 8 give it the power to regulate interstate commerce. Roland Dagenhart of North Carolina worked at a textile mill with his two teenage sons. HE believed the law was unconstitutional and sued, eventually taking his case to the Supreme Court. He made three constitutional arguments: a. He argued that the law was not a regulation of commerce. b. He believed the Tenth Amendment left the power to make rules for child labor to the states. c. His liberty and property protected by the 5th Amendment included the right to allow his children to work. Question: Does the congressional act violate the Commerce Clause, the Tenth Amendment, or the Fifth Amendment? Decision: Bottom Line: E. Carter v. Carter Coal Company (1936) Facts of the Case: The Bituminous Coal Conservation Act was passed in 1935 which established a commission made up of coal miners, coal producers, and the public, to establish fair competition standards, production standards, wages, hours, and labor relations. All mines were required to pay a 15% tax on coal produced. The act was not mandatory, but mines that complied would be refunded 90% of the 15% tax. James W. Carter was a shareholder of the Carter Coal Company and did not feel that the company should join the government program. The board of directors for the company thought that the company could not afford to pay the tax and not receive anything back. Carter sued, claiming that coal mining was not interstate commerce and therefore could not be regulated by Congress. Question: Does the United States Congress have the power, according to the Commerce Clause, to regulate the coal mining industry? Decision: Bottom Line: AP Government F. 2015-2016 West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937) Facts of the Case: In 1932, Washington State passed a law entitled “Minimum Wages for Women.” It called for minimum wages for women and children as a means to combat “pernicious effects on their health and morals” and provided for a special commission, with input from industry and the public, to determine appropriate minimum wage levels. Elsie Parrish, a chambermaid at the West Coast Hotel, later sued the hotel in a state court claiming that it had not paid her the law’s minimum wages. Parrish sought the balance of her income between what she was actually paid and the minimum wage (set at $14.50 per week of 48 hours). West Coast defended by arguing that the law was unconstitutional. The state court agreed and ruled for the hotel. Parrish appealed to the Washington Supreme Court, which reversed the lower court’s ruling and directed the damages be paid to Parrish. West Coast Hotel appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reviewed the case in 1936 and issued its opinion in 1937. Question: Did the minimum wage law violate the liberty of contract as construed under the Fifth Amendment as applied by the 14 th Amendment? Decision: Bottom Line: G. Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona (1945) Facts of the Case: The Arizona Train Limit Law of 1912 prohibited operating railroad trains of more than prescribed length. Reducing the length of the trains was said to increase safety because of less “slack action” which caused trains to behave uncontrollably. However, the length limit required the train operators to run about 30% more trains, and cost Southern Pacific about a million dollars a year in extra costs. About 95% of all rail traffic in Arizona was interstate, and so it affected train operations from Texas to California. In 1940, Arizona sued Southern Pacific for the statutory penalties for violating the law. The trial court found the law to be an unconstitutional burden on interstate commerce, and further found that it was not justified by local safety concerns because the increase in safety by reducing the slack action was offset by the decrease in safety of more trains. The State Supreme Court reversed, concluding that a state police law, based on safety, could not be overturned even though it had a substantial effect on interstate commerce. Question: Was the Arizona law an unconstitutional burden on interstate commerce? Decision: Bottom Line: H. Heart of Atlanta Motel v. U.S. (1964) Facts of the Case: Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbade racial discrimination by places of public accommodation if their operations affected commerce. The Heart of Atlanta Motel in Atlanta, Georgia, refused to accept Black Americans and was charged with violating Title II. Question: Did Congress, in passing Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, exceed its Commerce Clause powers by depriving motels, such as the Heart of Atlanta, of the right to choose their own customers? Decision: AP Government 2015-2016 Bottom Line: I. United States v. Lopez (1994) Facts of the Case: Alfonzo Lopez, a 12th grade high school student, carried a concealed weapon into his San Antonio, Texas high school. He was charged under Texas law with firearm possession on school premises. The next day, the state charges were dismissed after federal agents charged Lopez with violating a federal criminal statute, the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990. The act forbids “any individual knowingly to possess a firearm at a place that he knows…is a school zone.” Lopez was found guilty following a bench trial and sentenced to six months imprisonment and two years’ supervised release. Question: Is the 1990s Gun-Free School Zones Act, forbidding individuals from knowingly carrying a gun in a school zone, unconstitutional because it exceeds the power of Congress to legislate under the Commerce Clause? Decision: Bottom Line: J. United States v. Morrison (2000) Facts of the Case: In 1994, while enrolled at Virginia Polytechnic Institute (VT), Christy Brzonkala alleged that Antonio Morrison and James Crawford, both students and varsity football players at VT, raped her. In 1995, Brzonkala filed a complaint against Morrison and Crawford under VT’s Sexual Assault Policy. After a hearing, Morrison was found guilty of sexual assault and sentenced to immediate suspension for two semesters. Crawford was not punished. A second hearing found Morrison guilty. After an appeal through the university’s administrative system, Morrison’s punishment was set aside, as it was found to be “excessive.” Ultimately, Brzonkala dropped out of the university. Brzonkala then sued Morrison, Crawford, and Virginia Tech in Federal District Court, alleging that Morrison’s and Crawford’s attack violated part of the Violence Against Women Act of 1994, which provides a federal civil remedy for the victims of gender-motivated violence. Morrison and Crawford moved to dismiss Brzonkala’s suit on the ground that the civil remedy was unconstitutional. In dismissing the complaint, the District Court found that Congress lacked authority to enact it either under the Commerce Clause or the 14th Amendment, which Congress had explicitly identified as the sources of federal authority for it. Ultimately, the Court of Appeals affirmed. Question: Does Congress have the authority to enact the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 under either the Commerce Clause or the 14th Amendment? Decision: Bottom Line: K. Printz (Mack) v. United States (1997) Facts of the Case: The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act (Brady Bill) required “law chief law enforcement officers” to perform background-checks on prospective handgun purchasers, until such time as the Attorney General establishes a federal system for this purpose. County Sheriffs Jay Printz and Richard Mack, separately challenged the constitutionality of this interim provision of the Brady Bill on behalf of chief law enforcement officers in Montana and Arizona respectively. In both cases, District Courts found the background-checks unconstitutional, but ruled that since this requirement was severable from the rest of the Brady Bill a voluntary background-check system could remain. On appeal from the Ninth Circuit’s ruling that the interim background-check provisions were AP Government 2015-2016 constitutional, the Supreme Court granted certiorari and consolidated the two cases deciding this one along with Mack v. United States. Question: Using the Necessary and Proper Clause of Article I as justification, can Congress temporarily require state chief law enforcement officers to regulate handgun purchases by performing those duties called for by the Brady Bill’s handgun applicant background-checks? Decision: Bottom Line: V. Conclusion A. The Supremacy Clause, as stated in Article VI Clause 2, states the supremacy of the national government. B. However, the acceptance of the national government’s supremacy was established through various Supreme Court cases. C. While not always successful, the national government established its supremacy through the Implied Powers Clause and the Commerce Clause. Key Terms, Concepts, Events, People, and Places: Supremacy Clause Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee Implied Powers Elastic Clause McCulloch v. Maryland Commerce Clause Gibbons v. Ogden Lochner v. New York Right of Contract Hammer v. Dagenhart Carter v. Carter Coal Company West Coast Hotel v. Parrish Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona U.S. v. Lopez Heart of Atlanta Motel v. U.S. U.S. v. Morrison Printz (Mack) v. U.S. Questions to Consider: 1. Can federal courts impose the Supremacy Clause onto states? Support your answer with evidence. 2. What role did Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee play in supporting the Supremacy Clause? 3. How did the Federalists justify the need for Implied Powers? 4. How did McCulloch v. Maryland use the Necessary and Proper Clause? 5. What role McCulloch v. Maryland play in establishing the supremacy of the national government? 6. What role did Gibbons v. Ogden play in establishing the supremacy of the national government? 7. Explain the different ways in which the national government has used the Commerce Clause to increase their own power. Include both successes and failures. 8. Combine all the “Bottom Lines” from above.