juridical liability in healthcare

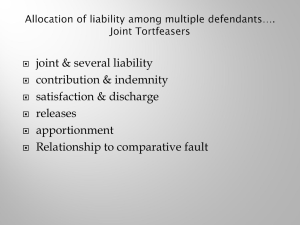

advertisement

Sources Delict in Roman law fell under the law of obligations.[5] Roman-Dutch law, based on Roman law, is the strongest influence on South Africa's common law, where delict also falls under the law of obligations. As has been pointed out, however, In contrast to the casuistic approach of the Roman law of delict, the South African law of delict is based [...] on three pillars: the actio legis Aquiliae, the actio iniuriarum and the action for pain and suffering. Unlike the lastmentioned action which developed in RomanDutch law, the first two remedies had already played an important role in Roman law. Damages Damages in delict are broadly divided into patrimonial damages, including medical costs, loss of income and the cost of repairs, which in turn fall under the heading of special damages; non-patrimonial damages, including pain and suffering, disfigurement, loss of amenities and injury to personality, which fall under the heading of general damages; and pure economic harm, which is not connected to any physical injury or damage to property. Liability Although delict may be described as at bottom a system of loss allocation, it is important to note that not every damage or loss will incur liability at law. "Sound policy," wrote Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr, "lets losses lie where they fall, except where a special reason can be shown for interference." As Christian von Bar puts it, "The law of delict can only operate as an effective, sensible and fair system of compensation if excessive liability is avoided. It is important to prevent it becoming a disruptive factor in an economic sense. No law based on rational principles can impose liability on each and every act of carelessness."[7] There are, for this reason, in-built mechanisms in the South African law of delict to keep liability within reasonable limits. The element of fault, introduced below, is one such. If its conditions are not met, liability will not arise Elements Van der Walt and Midgley list the elements of a delict as follows: "harm sustained by the plaintiff;" "conduct on the part of the defendant which is "wrongful;" "a causal connection between the conduct and the plaintiff's harm;" and "fault or blameworthiness on the part of the defendant Harm The harm element is "the cornerstone of the law of delict, and our fundamental point of departure."[10] Once the nature of the harm is identified, it is possible to identify the nature of the enquiry and the elements that need to be proven. There is an interplay between the elements of harm and wrongfulness, and a similar interaction between the way in which we determine harm and assess damages. "For conceptual clarity," suggest the academic authorities, "it is always important to remember where we are going along the problem-solving route towards the intended destination. Conduct It is vitally important that the conduct be voluntary. There must be no compulsion, in other words, and it must not be a reflex action. (The person engaging in the conduct must also be compos mentis or in sound mind and of sober senses, not unconscious or intoxicated, for example. He must be accountable for his actions, having the ability to distinguish between right and wrong, and to act accordingly. Unless this standard of accountability is secured, he will not be accountable for his actions or omissions. There will be no fault.) Conduct relates to overt behaviour, so that thoughts, for example, are not delictual. If it is a positive act or commission, it may be either physical or a statement or comment; if an omission—that is, a failure to do or say something—liability arises only in special circumstances. There is no general legal duty to prevent harm. Causation Conduct in the law of delict is usually divided into factual and legal causation. Factual causation is proven by a "demonstration that the wrongful act was a causa sine qua non of the loss." This is also known as the "but-for" test. A successful demonstration, however, "does not necessarily result in legal liability." Once factual causation is proved, a second enquiry arises: Is the wrongful act linked sufficiently closely or directly to the loss for legal liability to ensue? Is there legal liability, or is the loss "too remote"? This is basically a juridical problem. Considerations of policy may play a part in its solution.[12] The courts take a flexible approach based on considerations of reasonableness and fairness and justice, although there are misgivings. As the court put it in Fourway Haulage SA v SA National Roads Agency Considerations of fairness and equity must inevitably depend on the view of the individual judge. In considering the appropriate approach to wrongfulness, I said that any yardstick which renders the outcome of a dispute dependent on the idiosyncratic view of individual judges is unacceptable. The same principle must, in my view, apply with reference to remoteness. That is why I believe we should resist the temptation of a response that remoteness depends on what the judge regards as fair, reasonable and just in all the circumstances of that particular case. Though it presents itself as a criterion of general validity, it is, in reality, no criterion at all In summary, delictual liability requires a factual causal link between wrongful and culpable conduct, on the one hand, and loss suffered on the other. There must also be legal causation; the loss must not be too remote. To establish legal causation, the courts apply a flexible test based on reasonableness, fairness and justice, or policy and normative considerations. The flexible test, or "elastic test for legal causation," incorporates subsidiary tests; it does not replace them Rigidity, the court held in Smit v Abrahams,[16] is inconsistent with the flexible approach or criterion in South African law, whereby the court considers on the basis of policy considerations whether there is a sufficiently close connection between act and consequence. That question has to be answered on the basis of policy considerations and the limits of reasonableness, fairness and justice. Reasonable foreseeability cannot be regarded as the single decisive criterion for determining liability, but it can indeed be used as a subsidiary test in the application of the flexible criterion. The flexibility criterion is predominant; any attempt to detract from it should be resisted. Comparisons between the facts of the case which has to be resolved and the facts of other cases in which a solution has already been found can obviously be useful and of value sometimes decisive, but one should be careful not to attempt to distill fixed or generally applicable rules or principles from the process of comparison. There is only one principle, the court found: To determine whether the plaintiff's damages are too remote from the defendant's act to hold the defendant liable therefor, considerations of policy (reasonableness, fairness and justice) should be applied to the particular facts of the case A novus actus interveniens is an independent and extraneous factor or event which is not foreseeable and which actively contributes to the occurrence of harm after the original harm has occurred. This is the case, for example, in International Shipping v Bentley, where there was an auditing error, and in Mafesa v Parity, with a "crutch mishap." The talem qualem rule (or "thin-skull" or "eggskull" rule) provides that, in the words of Smit v Abrahams, "the wrongdoer takes his victim as he finds him."[18] An important case here is Smith v Leach Brain. Fault Fault refers to blameworthiness or culpability, while culpa is fault in a broad sense, in that it includes dolus and culpa in the strict sense. Accountability is a prerequisite for fault: The person at fault, to be at fault, must be culpae capax, having the ability to know the difference between right and wrong and to act accordingly. Unless one is in this sense accountable, one is not accountable for one's actions or omissions; one is, in other words, culpa incapax. It is important to remember that there is a distinction between the question of absence of voluntariness of conduct and that of accountability. Voluntary conduct entails no compulsion; the conduct must not have been reflex; the person must have been compos mentis, or of sound mind and sober senses, not unconscious, intoxicated etcetera. Accountability relates to overt behaviour (Thoughts cannot be delictual.) There must be some positive act or commission, either physical or in the form of a statement or comment, or else an omission: a failure to do or say something. Liability only arises in special circumstances: There is no general legal duty to prevent harm. Factors excluding liability include youth or emotional and intellectual immaturity;[20][21] mental disease or illness, or emotional distress;[22] intoxication;[23] and provocation. There are two main components of intention: direction of the will (the manner in which the will is directed): dolus directus; dolus indirectus; and dolus eventualis; consciousness of wrongfulness Animus iniuriani arises when both requirements—direction of will and knowledge of wrongfulness—are satisfied. The test is subjective. There are exceptions to the requirement of knowledge of wrongfulness, as in the case of deprivation of liberty or wrongful arrest, which results in attentuated animus iniuriandi.[26] There are several defences which exclude intent: mistake;[27] jest; intoxication; provocation; and emotional distress. The test for negligence is one of the objective or reasonable person (bonus paterfamilias). The test requires "an adequate and consistent level of care on the part of all legal subjects." It "does not represent a standard of exceptional skill, giftedness or care but does also not represent a standard of undeveloped skills, recklessness or thoughtlessness." It is the standard of the ordinary individual who takes reasonable chances and reasonable precautions. The test has two pillars: foreseeability, the likelihood or degree or extent of risk created by the conduct; and the gravity of possible consequences; and preventability, which refers to under which heading may fall utility of conduct; and burden. Harm or loss One obvious prerequisite for liability in terms of the law of delict is that the plaintiff must have suffered harm; in terms of the lex Aquilia, that harm must be patrimonial, which traditionally meant monetary loss sustained due to physical damage to a person or property. Now, however, patrimonial loss also includes monetary loss resulting from injury to the nervous system and pure economic loss. A plaintiff may claim compensation both for loss actually incurred and for prospective loss, including, for instance, the loss of earning capacity, future profits, income and future expenses.