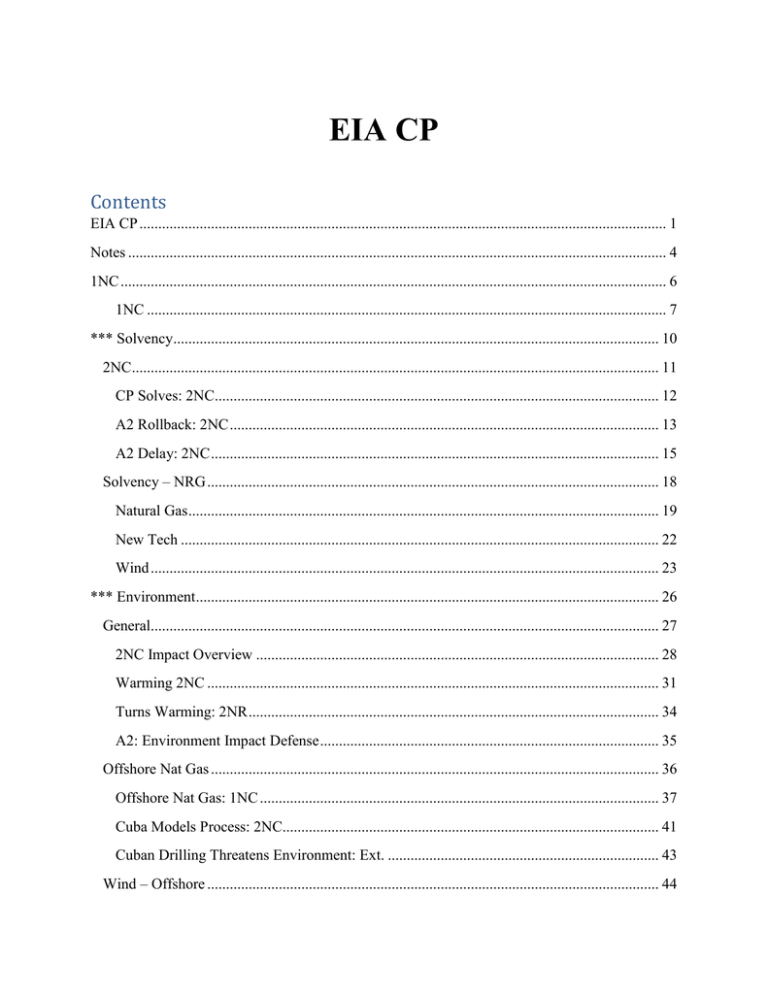

EIA CP - ENDI 14

advertisement