PROMPT: Many high schools, colleges, and universities have honor

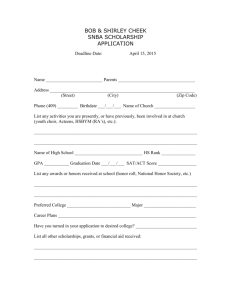

advertisement

PROMPT: Many high schools, colleges, and universities have honor codes or honor systems: sets of rules or principles that are intended to cultivate integrity. These rules or principles often take the form of written positions on practices like cheating, stealing, and plagiarizing as well as on the consequences of violating the established codes. Carefully read the following sources, including the introductory information for each source. Then, using at least three of the sources and incorporate it into a coherent, well-developed argument for your own position on whether your school should establish, maintain, revise, or eliminate an honor code or honor system 1. Vangelli, Alyssa. “The Honor Code Vote: One Student Senator’s View.” ParentsAssociation.com. ParentsAssociation.com, n.d. Web. 1 April 2013 The following, an excerpt from a student’s account of the introduction of an honor code at her high school, Lawrence Academy—a private boarding school in Massachusetts—was originally published in the school newsletter in May 1999. When the honor code proposal first came under consideration in the spring of 1998, many students, including members of the Senate, were quick to criticize it. Students did not fully understand the role of an honor code; many saw it as another rule to obey. The earlier drafts of the honor code included specific penalties for violations of the honor code, which many students opposed. Students were expected to report or confront a fellow student if they knew that he/she had cheated, lied, or stolen. Failure to confront or report a student would result in a period of probation. Students opposed this obligation to take action against another student because they did not see it as their responsibility. They feared that a mandate to confront peers would create friction and that a subsequent report could not easily be kept confidential. . . . After much discussion and debate in class and Senate meetings, the proposal was revised to eliminate any formal disciplinary actions, although the expectation to take action if one witnessed or knew about any dishonest behavior still existed. I saw the revision to eliminate all formal penalties in the honor code as a huge step in gaining student approval, both inside and outside of the Senate. Another part of the code which received student criticism was a requirement for students to write a pledge of honor on every piece of work submitted, stating that it was the result of their own thinking and effort. Many students thought that a pledge of honor for each piece of paper submitted was excessive, but a less frequent pledge of honor could be a helpful reminder of their responsibilities. This section was revised to require a pledge of honor at the beginning of each term, affirming that each student will behave honestly and responsibly at all times. In signing this pledge of honor, students have reminders of these moral values and a responsibility to perform honestly in the school environment. The revised pledge of honor also helped gain student approval for the honor code. Another turning point occurred when students began to examine the role of an honor code as something other than a new set of rules and regulations to obey. In order to understand the purpose of an honor code, the real question was what type of environment we wanted to live in. As Senate members, we brought this question to class meetings for discussion. Most responded that we needed an environment where students and faculty could live in complete trust of one another. Although some did not see a need for an honor code, we, as Senate members, concluded that this type of environment could only be achieved through first adopting an honor code. Implicit in an honor code is a belief in the integrity of human beings; it also provides students a clear explanation of the importance of behaving with the integrity and the expectation that our resulting actions will increase trust and respect in the LA [Lawrence Academy] community. As the time to vote for the honor code approached, I and many other student members of the Senate felt pulled in two directions; we wanted to vote based on our consciences, but we wanted to represent the remaining skeptical and uncertain views of our fellow students. At the time of voting, most of us took the first option and voted according to our consciences, which we believed would eventually benefit every member of the school. I voted in favor because I wanted to go to a school where I could feel comfortable taking an exam without worrying about someone looking at my paper and where I could be trusted visiting a dorm as a day student. I imagined that other students and future students of Lawrence would feel the same way. Although the full acceptance of an honor code will take time, an important process has begun, one which I believe will ensure moral action and thinking here at Lawrence Academy. 2. Dirmeyer, Jennifer, and Alexander Cartwright. “Honor Codes Work Where Honesty Has Already Taken Root.” Chronicle of Higher Education. Chronicle of Higher Education, 24 Sept. 2012. Web. 20 March 2013. The following is excerpted from a commentary published in an online newspaper focused on higher education. The possibility that 125 Harvard students “improperly collaborated” on an exam in the spring has galvanized a continuing discussion about the use of honor codes. While Harvard administrators hope that an honor code can improve the academic integrity of the college, critics—especially Harvard students—are skeptical that signing a piece of paper will suddenly cause a cheater to change his ways. They’re right. Not all colleges have what it takes to make an honor code effective—not because the students aren’t honest, but because they don’t expect anyone else to be. And with honor codes, expectations determine reality. According to research by Donald L. McCabe, a professor of management at Rutgers University who specializes in student integrity, students at colleges with honor codes—typically student-enforced—cheat less than their counterparts elsewhere do. Our experience at Hampden-Sydney College would seem to support this conclusion: We find little evidence of cheating, even when professors work in their offices during exams. Indeed, you have not seen an honor code at work until you have seen a show of hands for those who did not do the reading for today’s class turn out to be completely accurate. Our honor code is strictly enforced, and the enforcement is handled by an all-student court. Students convicted of lying or cheating can expect to receive punishments ranging from suspension to expulsion. However, honor codes don’t always work. Mr. McCabe says that their success depends on a “culture of academic integrity” that leads students to take enforcement of the rules seriously. But economic theory suggests that it’s more a matter of expectations. When it works, the culture makes for a successful honor code as much as the honor code makes for a successful culture. Student expectations about the integrity of their classmates can determine whether the college culture reinforces honesty. Say that each student arrives as a “cheater” type, an “honest” type, or somewhere on the continuum between them. Whatever the individual’s innate level of integrity, we believe that each student will decide whether or not to cheat by weighing the costs and benefits. With a peer-enforced honor code, the likelihood of being caught depends on other students’ tolerance for cheating. Students who enter a college of mostly “honest” types will more often choose not to cheat even if they are innately “cheater” types, because the higher risk of getting caught makes the costs greater. That leads to a feedback loop, as more of the population behaves like “honest” types than normally would, increasing the impression that everyone is honest and raising still higher the expectation of being caught. This feedback loop generates the culture of trust and integrity that students—like those at, say, Davidson College, which has a well-publicized honor code—reportedly value so highly. Unfortunately, the feedback loop can go the other way. If a student enters a college with mostly “cheater” types, not only are the costs of cheating very low, encouraging fellow “cheater” types to cheat, but the benefits of cheating (or the costs of not cheating) are very high, encouraging even “honest” types to cheat. That leads more students to cheat than would normally do so, creating a culture of dishonesty. The success of the honor code, then, depends on the expectations that students have of their peers’ behavior, which is why colleges with successful honor codes must invest considerable resources in programs that influence how the honor code is perceived. 3. Kahn, Chris. “Pssst—How Do Ya Spell Plagiarism ? Cheating Scandal Tests Honor Code at U. Va.” Daily Press. Daily Press Media Group, 14 April 2002. Web. 10 Sept. 2013. The following is excerpted from an article in a regional newspaper headquartered in Newport News, Virginia. At the University of Virginia, there’s a saying that students soon commit to memory: “On my honor as a student, I have neither given nor received aid on this assignment/exam.” Students write this on every test in every class during their college career, pledging as their predecessors have since 1842 never to lie, cheat or steal. It’s a tradition that’s made Thomas Jefferson’s school a richer academic environment, students say, as well as an easier place to find lost wallets. But even here, where honor is so well defined and policed by an elite student committee, plagiarism has become a problem. Since last spring, 157 students have been investigated by their peers in the largest cheating scandal in memory. Thirty-nine of those accused of violating the school’s honor code have either dropped out or been expelled—the only penalty available for such a crime. Some students who had already graduated lost their diplomas. “It’s not like we’re saying we hate you, it’s just that we have standards here,” said 22-year-old Cara Coolbaugh, one of the students on U.Va.’s Honor Committee who has spent countless hours this year determining the fate of her peers. The scandal began in a popular introductory physics class designed for non-majors. The course, which explores pragmatic topics such as why the sky is blue and how light bulbs work, usually attracts 300 to 500 students per semester—too many to watch closely. Instructor Lou Bloomfield said he started to worry about plagiarism after a student confided that some of her friends had copied papers from a file at their sorority. To find out for sure, Bloomfield spent an afternoon programming a computer to spot repeated phrases. He fed in computer files of 1,500 term papers from four semesters of classes, and matches started popping up. “I was disappointed,” Bloomfield said. “But I wasn’t so surprised—I have a large class.” A few of his students had simply copied from earlier work. Others had lifted at least a third of their papers from someone else. The Honor Committee, whose 21 members were elected just before the plagiarism scandal hit, was overwhelmed. Most professors usually have a few people they’d like to investigate. Bloomfield handed over a list of more than 100. Philip Altbach, a higher education scholar at Boston College, said he isn’t surprised. “Plagiarism is more common now,” he said. “It’s just easier to do.” The Internet provides an inexhaustible source of information, and it’s tempting to simply insert phrases directly into reports, Altbach said. 4. McCabe, Donald, and Gary Pavela. “New Honor Codes for a New Generation.” Inside Higher Ed. Inside Higher Ed, 11 March 2005. Web. 20 March 2013. The following is excerpted from an opinion piece published in an online publication focused on higher education. Research confirms recent media reports concerning the high levels of cheating that exist in many American high schools, with roughly two-thirds of students acknowledging one or more incidents of explicit cheating in the last year. Unfortunately, it appears many students view high school as simply an annoying obstacle on the way to college, a place where they learn little of value, where teachers are unreasonable or unfair, and where, since “everyone else” is cheating, they have no choice but to do the same to remain competitive. And there is growing evidence many students take these habits with them to college. At the college level, more than half of all students surveyed acknowledge at least one incident of serious cheating in the past academic year and more than twothirds admit to one or more “questionable” behaviors—e.g., collaborating on assignments when specifically asked for individual work. We believe it is significant that the highest levels of cheating are usually found at colleges that have not engaged their students in active dialogue on the issue of academic dishonesty—colleges where the academic integrity policy is basically dictated to students and where students play little or no role in promoting academic integrity or adjudicating suspected incidents of cheating. The Impact of Honor Codes A number of colleges have found effective ways to reduce cheating and plagiarism. The key to their success seems to be encouraging student involvement in developing community standards on academic dishonesty and ensuring their subsequent acceptance by the larger student community. Many of these colleges employ academic honor codes to accomplish these objectives. Unlike the majority of colleges where proctoring of tests and exams is the responsibility of the faculty and/or administration, many schools with academic honor codes allow students to take their exams without proctors present, relying on peer monitoring to control cheating. Yet research indicates that the significantly lower levels of cheating reported at honor code schools do not reflect a greater fear of being reported or caught. Rather, a more important factor seems to be the peer culture that develops on honor code campuses—a culture that makes most forms of serious cheating socially unacceptable among the majority of students. Many students would simply be embarrassed to have other students find out they were cheating. In essence, the efforts expended at these schools to help students understand the value of academic integrity, and the responsibilities they have assumed as members of the campus community, convince many students, most of whom have cheated in high school, to change their behavior. Except for cheating behaviors that most students consider trivial (e.g., unpermitted collaboration on graded assignments), we see significantly less self-reported cheating on campuses with honor codes compared to those without such codes. The critical difference seems to be an ongoing dialogue that takes place among students on campuses with strong honor code traditions, and occasionally between students and relevant faculty and administrators, which seeks to define where, from a student perspective, “trivial” cheating becomes serious. While similar conversations occasionally take place on campuses that do not have honor codes, they occur much less frequently and often do not involve students in any systematic or meaningful way. Look at the sources below.. The sources are: • “Declaration of Independence,” signed on July 4, 1776 • A passage from Patrick Henry’s March 23, 1776, “Speech to the Second Virginia Convention” • The transcript of the video “From Subjects to Citizens” An important idea presented in the sources involves the colonists’ notions of the purpose of government. Write an essay in which you explore the perspectives offered in the source documents regarding government’s purpose and its relationship to the people it governs. Use evidence from all three source documents to support your ideas. The Declaration of Independence: A Transcription IN CONGRESS, July 4, 1776. The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, -That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.-Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world. He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people. He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within. He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries. He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance. He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power. He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies: For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people. Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends. We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor. St. John's Church, Richmond, Virginia March 23, 1775. MR. PRESIDENT: No man thinks more highly than I do of the patriotism, as well as abilities, of the very worthy gentlemen who have just addressed the House. But different men often see the same subject in different lights; and, therefore, I hope it will not be thought disrespectful to those gentlemen if, entertaining as I do, opinions of a character very opposite to theirs, I shall speak forth my sentiments freely, and without reserve. This is no time for ceremony. The question before the House is one of awful moment to this country. For my own part, I consider it as nothing less than a question of freedom or slavery; and in proportion to the magnitude of the subject ought to be the freedom of the debate. It is only in this way that we can hope to arrive at truth, and fulfil the great responsibility which we hold to God and our country. Should I keep back my opinions at such a time, through fear of giving offence, I should consider myself as guilty of treason towards my country, and of an act of disloyalty toward the majesty of heaven, which I revere above all earthly kings. Mr. President, it is natural to man to indulge in the illusions of hope. We are apt to shut our eyes against a painful truth, and listen to the song of that siren till she transforms us into beasts. Is this the part of wise men, engaged in a great and arduous struggle for liberty? Are we disposed to be of the number of those who, having eyes, see not, and, having ears, hear not, the things which so nearly concern their temporal salvation? For my part, whatever anguish of spirit it may cost, I am willing to know the whole truth; to know the worst, and to provide for it. I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided; and that is the lamp of experience. I know of no way of judging of the future but by the past. And judging by the past, I wish to know what there has been in the conduct of the British ministry for the last ten years, to justify those hopes with which gentlemen have been pleased to solace themselves, and the House? Is it that insidious smile with which our petition has been lately received? Trust it not, sir; it will prove a snare to your feet. Suffer not yourselves to be betrayed with a kiss. Ask yourselves how this gracious reception of our petition comports with these war-like preparations which cover our waters and darken our land. Are fleets and armies necessary to a work of love and reconciliation? Have we shown ourselves so unwilling to be reconciled, that force must be called in to win back our love? Let us not deceive ourselves, sir. These are the implements of war and subjugation; the last arguments to which kings resort. I ask, gentlemen, sir, what means this martial array, if its purpose be not to force us to submission? Can gentlemen assign any other possible motive for it? Has Great Britain any enemy, in this quarter of the world, to call for all this accumulation of navies and armies? No, sir, she has none. They are meant for us; they can be meant for no other. They are sent over to bind and rivet upon us those chains which the British ministry have been so long forging. And what have we to oppose to them? Shall we try argument? Sir, we have been trying that for the last ten years. Have we anything new to offer upon the subject? Nothing. We have held the subject up in every light of which it is capable; but it has been all in vain. Shall we resort to entreaty and humble supplication? What terms shall we find which have not been already exhausted? Let us not, I beseech you, sir, deceive ourselves. Sir, we have done everything that could be done, to avert the storm which is now coming on. We have petitioned; we have remonstrated; we have supplicated; we have prostrated ourselves before the throne, and have implored its interposition to arrest the tyrannical hands of the ministry and Parliament. Our petitions have been slighted; our remonstrances have produced additional violence and insult; our supplications have been disregarded; and we have been spurned, with contempt, from the foot of the throne. In vain, after these things, may we indulge the fond hope of peace and reconciliation. There is no longer any room for hope. If we wish to be free² if we mean to preserve inviolate those inestimable privileges for which we have been so long contending²if we mean not basely to abandon the noble struggle in which we have been so long engaged, and which we have pledged ourselves never to abandon until the glorious object of our contest shall be obtained, we must fight! I repeat it, sir, we must fight! An appeal to arms and to the God of Hosts is all that is left us! They tell us, sir, that we are weak; unable to cope with so formidable an adversary. But when shall we be stronger? Will it be the next week, or the next year? Will it be when we are totally disarmed, and when a British guard shall be stationed in every house? Shall we gather strength by irresolution and inaction? Shall we acquire the means of effectual resistance, by lying supinely on our backs, and hugging the delusive phantom of hope, until our enemies shall have bound us hand and foot? Sir, we are not weak if we make a proper use of those means which the God of nature hath placed in our power. Three millions of people, armed in the holy cause of liberty, and in such a country as that which we possess, are invincible by any force which our enemy can send against us. Besides, sir, we shall not fight our battles alone. There is a just God who presides over the destinies of nations; and who will raise up friends to fight our battles for us. The battle, sir, is not to the strong alone; it is to the vigilant, the active, the brave. Besides, sir, we have no election. If we were base enough to desire it, it is now too late to retire from the contest. There is no retreat but in submission and slavery! Our chains are forged! Their clanking may be heard on the plains of Boston! The war is inevitable²and let it come! I repeat it, sir, let it come. It is in vain, sir, to extenuate the matter. Gentlemen may cry, Peace, Peace²but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death! Read the transcript of a video by the Kettering Foundation about a recent finding about the “Declaration of Independence.” Then answer question 13. Transcript of “From Subjects to Citizens” by the Kettering Foundation New advances in science have uncovered a fascinating twist in the writing of the Declaration of Independence, one that’s still of interest to the Kettering Foundation today. Spectral imaging technology shows that in writing the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson had first referred to the American colonists as “subjects.” But, in the course of revising the document, he then carefully expunged the word, smearing the ink and overwriting it with the word “citizens,” so as to completely obliterate the original word. The sentence in which Jefferson made the change didn’t make it into the final document, but the word “citizens” is also used elsewhere in the final Declaration, while “subjects” is not. This finding reveals an important shift in the Founders’ thinking: that the people’s allegiance was to one another, not to a distant king. That change in thinking, from “subject” to “citizen,” is the starting point for Kettering Foundation’s view of democracy.