Northwestern-Hopkins-Srinivasan-Aff-Texas

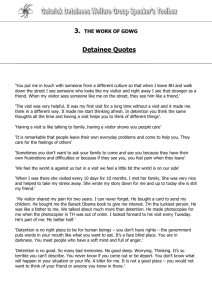

advertisement