Credit Rating Agencies

advertisement

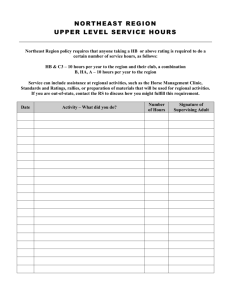

Credit Rating Agencies Paola Lucantoni The G20 summit in Washington (2008) aimed to ensure that no institution, product or market was left unregulated at EU and international levels. The EU Regulation on Credit Rating Agencies (Regulation 1060/2009), in force since December 2010, was part of Europe's response to these commitments. The Regulation was amended in May 2011 to adapt it to the creation of the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) which has been attributed all supervisory powers over credit rating agencies since July 2011. The new regulatory package, which reinforces the existing rules on credit rating agencies, consists of a Regulation and a Directive: Regulation 462/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2013 amending Regulation (EC) No 1060/2009 on credit rating agencies Directive 2013/14/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2013 amending Directive 2003/41/EC on the activities and supervision of institutions for occupational retirement provision, Directive 2009/65/EC on the coordination of laws, regulations and administrative provisions relating to undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities (UCITS) and Directive 2011/61/EU on Alternative Investment Funds Managers in respect of over-reliance on credit ratings What is a credit rating? A credit rating is an opinion issued by a specialised firm on the creditworthiness of an entity (e.g. an issuer of bonds) or a debt instrument (e.g. bonds or assetbacked securities). This opinion is based on research activity and presented according to a ranking system. Why is it necessary to regulate credit rating agencies? CRAs have a major impact on today's financial markets, with rating actions being closely followed and impacting on investors, borrowers, issuers and governments: e.g. sovereign ratings play a crucial role for the rated country, since a downgrading can have the immediate effect of making a country's borrowing more expensive. A downgrading also has a direct impact for example on the capital levels of a financial institution. The financial crisis and developments in the context of the euro debt crisis have revealed serious weaknesses in the existing EU rules on credit ratings. In the run up to the financial crisis, CRAs failed to appreciate properly the risks inherent in more complicated financial instruments (especially structured financial products backed by risky subprime mortgages), issuing incorrect ratings that were far too high. What did previously applicable EU rules on credit rating agencies say? The EU Regulation on Credit Rating Agencies (CRA I Regulation)1, in force since December 2010, was part of Europe's response to these commitments. The Regulation was amended in May 2011 to adapt it to the creation of the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) by the so called CRA II Regulation These CRA Regulations focused on: registration: in order to be registered, a CRA must fulfill a number of obligations on the conduct of their business (see below), intended to ensure the independence and integrity of the rating process and to enhance the quality of the ratings issued. ESMA is entrusted since July 2011 with responsibility for registering and directly supervising CRAs in the EU; conduct of business: the previous Regulation (CRA I) required CRAs to avoid conflicts of interest (for example, a rating analyst employed by a CRA should not rate an entity in which he/she has an ownership interest), to ensure the quality of ratings (for example, requiring the ongoing monitoring of credit ratings) and rating methodologies (which must be, inter alia, rigorous and systematic) and a high level of transparency (for example, every year the CRA should publish a Transparency Report); supervision: ESMA has comprehensive investigatory powers including the possibility to demand any document or data, to summon and hear persons, to conduct on-site inspections and to impose administrative sanctions, fines and periodic penalty payments. This centralises and simplifies the supervision of CRAs at European level. Centralised supervision ensures a single point of contact for registered CRAs, significant efficiency gains due to a shorter and less complicated registration and supervisory process and a more consistent application of the rules for CRAs. The CRA II Regulation, however, did not regulate the use of credit ratings and their impact on the market. The use of external ratings by financial institutions was previously regulated in sectoral financial legislation (e.g. in the Capital Requirements Directive). What has already been proposed to reduce the risk of overreliance in the banking sector? The new rules on capital requirements (Capital Requirements Directive IV) include measures to reduce overreliance on ratings (MEMO/13/272). Possible overreliance by credit institutions on external credit ratings is to be reduced to the extent possible by: requiring that all banks' investment decisions are based not only on ratings but also on their own internal credit opinion, that banks with a material number of exposures in a given portfolio develop internal ratings for that portfolio instead of relying on external ratings for the calculation of their capital requirements. CRD IV rules will apply as from the January 2014. What is the situation at international level? Are the new rules in line with the regulatory approaches of other jurisdictions and international standard setting bodies? The new rules are broadly in line with the policy developed by our international partners within the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and the Basel Committee. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) endorsed in October 2010 principles to reduce the overreliance of authorities and financial institutions on CRA ratings. The G20 approved the FSB's principles on reducing reliance on external credit ratings (Seoul Summit, 11-12 November 2010). At the end of 2012, the FSB adopted a roadmap to accelerate the implementation of the principles. The aims of these principles are twofold: the removal or replacement of references to CRA ratings in laws and regulations, wherever possible, with suitable alternative standards of creditworthiness assessment; that banks, market participants and institutional investors make their own credit assessments, and not rely solely or mechanically on CRA ratings. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has also proposed to reduce overreliance on credit rating agencies' ratings in the regulatory capital framework. In the USA, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act3 has strengthened rules on CRAs. Among other things section 939A of the Dodd-Frank Act requires federal agencies to review how existing regulations rely on ratings and remove such references from their rules as appropriate. As a consequence, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is exploring ways to reduce regulatory reliance on external credit ratings and replace them with alternative criteria. Some references have already been replaced in US legislation. Why was a reform of the CRA Regulation needed? non-transparent sovereign ratings: Downgrading sovereign ratings has immediate consequences on the stability of financial markets but CRAs are insufficiently transparent about their reasons for attributing a particular rating to sovereign debt. Given the importance of ratings on sovereign debts, it is essential that ratings of this asset class are both timely and transparent. While the EU regulatory framework for credit ratings already contains measures on disclosure and transparency that apply to sovereign debt ratings, further measures are needed such as access to more comprehensive information on the data and reasons underlying a rating, in order to improve the process of sovereign debt ratings in EU; investors' over-reliance on ratings: European and national laws give a quasi-institutional role to ratings. For example, the amount of capital that banks must hold is determined in some cases by the external ratings given to it. Furthermore, some investors rely excessively on the opinions of CRAs, and don’t have access to enough information on the debt instruments rated or the reasons behind the credit rating which would enable them to conduct their own credit risk assessments. Measures were needed to reduce references to external ratings in legislation and to ensure investors carry out their own additional due diligence on a well-informed basis; conflicts of interest threaten independence of CRAs and high market concentration: CRAs are not independent enough from the rated entity that contracts (and pays) them: e.g. as a rating agency has a financial interest in generating business from the issuer that seeks the rating, this could lead to assigning a higher rating than warranted in order to encourage the issuer to contract them again in the future. Furthermore, a small number of large CRAs dominate the market. The rating of large corporates and complex structured finance products is conducted by a few agencies that also happen to have shareholders that sometimes overlap; (absence of) liability of CRAs: CRAs issuing credit ratings in violation of the CRA Regulation are not always liable towards investors that suffered losses. National differences in civil liability regimes could result in credit rating agencies or issuers shopping around, choosing jurisdictions under which civil liability is less likely. The main elements of the new rules are: 1. Reduce overreliance on credit ratings In line with G20 commitments, the new rules aim to reduce overreliance on external ratings, requiring financial institutions to strengthen their own credit risk assessment and not to rely solely and mechanistically on external credit ratings. The package consists of a Regulation setting out the principles to reduce overreliance on external credit ratings. Furthermore, the Regulation is complemented with amendments in sectoral legislation. Specifically, the package contains a Directive which amends current directives on the activities and supervision of institutions for occupational retirement provision (IORP6) undertakings of collective investment in transferable securities (UCITS)7 and on alternative investment funds managers (AIFM)8 in order to reduce these funds' reliance on external credit ratings when assessing the creditworthiness of their assets. Also the European Supervisory Authorities9 should avoid references to external credit ratings and will be required to review their rules and guidelines and where appropriate, remove credit ratings where they have the potential to create mechanistic effects. 2. Improve quality of ratings of sovereign debt of EU Member States To avoid market disruption, rating agencies will set up a calendar indicating when they will rate Member States. Such ratings will be limited to three per year for unsolicited sovereign ratings. Derogations remain possible in exceptional circumstances and subject to appropriate explanations. The ratings will only be published on Fridays after close of business and at least one hour before the opening of trading venues in the EU. Furthermore, investors and Member States will be informed of the underlying facts and assumptions on each rating which will facilitate a better understanding of credit ratings of Member States. Moreover, sovereign ratings would have to be reviewed at least every six months (rather than every 12 months as currently applicable under general rules). 3. Make credit rating agencies more accountable for their actions The new rules will make rating agencies more accountable for their actions as ratings are not just simple opinions. Therefore, the new rules ensure that a rating agency can be held liable in case it infringes intentionally or with gross negligence, the CRA Regulation, thereby causing damage to an investor. 4. Reduce conflicts of interests due to the issuer pays remuneration model and encourage the entrance of more players on to the credit rating market The Regulation will also improve independence of credit rating agencies to eliminate conflicts of interests by introducing new rules for complex structured finance instruments and shareholders of rating agencies. Issuers of structured finance instruments will be required to be more transparent on the underlying assets of these instruments. Furthermore, all available ratings will be published on a European Rating Platform which will improve comparability and visibility of all ratings for any financial instrument rated by rating agencies registered and authorised in the EU. This should also help investors to make their own credit risk assessment and contribute to more diversity in the rating industry. The Regulation will improve the independence of credit rating agencies and help eliminate conflicts of interest by introducing mandatory rotation for certain complex structured financial instruments (re-securitisations). There are also limitations as regards the shareholding of rating agencies. The principal ways by which the new Regulation will improve the independence of credit rating agencies are: a) To mitigate the risk of conflicts of interest, the new rules will require CRAs to disclose publicly if a shareholder with 5% or more of the capital or voting rights of the concerned CRA holds 5% or more of a rated entity, and would prohibit a CRA from rating when a shareholder of a CRA with 10% or more of the capital or voting rights also holds 10% or more of a rated entity. b) Furthermore, to ensure the diversity and independence of credit ratings and opinions, the proposal prohibits ownership of 5% or more of the capital or the voting rights in more than one CRA, unless the agencies concerned belong to the same group (crossshareholding). c) Due to the complexity of structured finance instruments and their role in contributing to the financial crisis, the Regulation also requires the issuers, who pay credit rating agencies for their ratings, to engage at least two different CRAs for the rating of structured finance instruments. d) The Regulation introduces a mandatory rotation rule forcing issuers of structured finance products with underlying re-securitised assets, who pay CRAs for their ratings ("issuer pays model"), to switch to a different agency every four years. An outgoing CRA would not be allowed to rate re-securitised products of the same issuer for a period equal to the duration of the expired contract, though not exceeding four years. But mandatory rotation will not apply to small CRAs, or to issuers employing at least four CRAs each rating more than 10% of the total number of outstanding rated structured finance instruments A review clause provides the possibility for mandatory rotation to be extended to other instruments in the future. Mandatory rotation would not be a requirement for the endorsement and equivalence assessment of third country CRAs. e) Measures are taken to encourage the use of smaller credit rating agencies. The issuer should consider the possibility to mandate at least one credit rating agency which does not have more than 10 % of the total market share and which could be evaluated by the issuer as capable for rating the relevant issuance or entity (Comply or Explain). WHAT WILL CHANGE? Who will be affected by the changes and how? Corporate, structured finance instruments’ and sovereign issuers: They will benefit from more choice of rating providers which may lead to lower rating fees in the medium term. Sovereign issuers (e.g. states and municipalities) will benefit from the improved transparency and process of issuing sovereign ratings. From now on, an issuer of structured finance products with underlying re-securitised assets who pays credit rating agencies for their ratings ("issuer pays model") will be required to switch to a different agency every four years. An outgoing credit rating agency would not be allowed to rate re-securitised products of the same issuer for a period equal to the duration of the expired contract, though not exceeding four years. But mandatory rotation would not apply to small credit rating agencies or to issuers employing at least four credit rating agencies each rating more than 10% of the total number of outstanding rated structured finance instruments. An issuer of structured finance instruments, who pays credit rating agencies for their ratings, will need to engage at least two different credit rating agencies. Moreover, an issuer, an originator and a sponsor of a structured finance instrument established in the Union will jointly need to disclose to the public information on the credit quality and performance of the underlying assets of the structured finance instrument, the structure of the securitisation transaction, the cash flows and any collateral supporting a securitisation exposure as well as any information that is necessary to conduct comprehensive and well informed stress tests on the cash flows and collateral values supporting the underlying exposures. All issuers, including sovereigns, will enjoy additional time to react to ratings before they are made public. The current rules already provide for ratings to be announced to the rated entity 12 hours before their publication. In order to avoid that this notification takes place outside working hours and to leave the rated entity sufficient time to verify the correctness of data underlying the rating, the new rules will require that the rated entity should be notified during working hours of the rated entity and at least a full working day before publication of the credit rating or the rating outlook. A list of the persons able to receive this notification a full working day before publication of a rating or of a rating outlook should be limited and clearly identified by the rated entity. This information shall include the principal grounds on which the rating or outlook is based in order to give the entity an opportunity to draw attention of the credit rating agency to any factual errors. The publication of sovereign ratings will be done in a manner that is least distortive on markets: at the end of December, credit rating agencies should publish a calendar for the next 12 months setting the dates for the publication of sovereign ratings and corresponding to these, the dates for the publication of related outlooks where applicable. Such dates should be set on a Friday. Only for unsolicited sovereign credit ratings should the number of publications in the calendar be limited between two and three. Where this is necessary to comply with their legal obligations, credit rating agencies should be allowed to deviate from their announced calendar explaining in detail the reasons for such deviation. However, this deviation may not happen routinely. Investors: They will be in a better position to evaluate the credit risk of financial instruments themselves, including complex structured instruments. They will have free access to a European Rating Platform where all ratings issued by rating agencies, registered and authorised in the EU, regarding a specific company or financial instruments can be found and compared. In addition, investors will benefit from an increase in the quality of ratings as conflicts of interest due to the "issuer-pays" model and the shareholder structure will be reduced. The investor will benefit from enhanced transparency on structured finance instrument established in the European Union as the issuer, the originator and the sponsor of a structured finance instrument established in the EU will jointly disclose to the public information on the credit quality and performance of the underlying assets of the structured finance instrument, the structure of the securitisation transaction, the cash flows and any collateral supporting a securitisation exposure as well as any information that is necessary to conduct comprehensive and well informed stress tests on the cash flows and collateral values supporting the underlying exposures. ESMA will set up a webpage for the publication of the information on structured finance instruments. Furthermore, the investors' right of redress against credit rating agencies having infringed the CRA Regulation are enhanced. The new rules ensure that a rating agency can be held liable in case it infringes intentionally or with gross negligence, the CRA Regulation, thereby causing damage to an investor or an issuer. Credit rating agencies that will need to: be more transparent notably regarding their pricing policy and the fees they receive. be more transparent about how they conduct their process of rating and reach their conclusions. be more independent from their shareholder base and from other CRAs. be liable towards investors when breaching intentionally or with gross negligence the CRA Regulation. The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) Its role will be reinforced regarding supervision of sovereign ratings. In addition, ESMA will be entrusted with new tasks e.g. it will have to draft a number of new technical standards for adoption by the Commission as well as to provide the Commission with technical advice. For instance, ESMA should establish a European Rating Platform so as to allow investors to easily compare all ratings for EU-registered and authorised rating agencies that exist with regard to a specific rated entity. ESMA will need to develop draft regulatory technical standards to specify the content to be used by CRAs when providing such information. Regarding the new rating methodologies: A CRA that intends to change materially existing or use any new rating methodologies, models or key rating assumptions that could have an impact on a credit rating will need to publish the proposed changes or proposed new methodologies on its website inviting stakeholders to submit comments during a period of one month together with a detailed explanation of the reasons for and the implications of the proposed material changes or proposed new methodologies. A CRA will need to inform ESMA of errors detected in methodologies and/or their application. Regarding existing ratings: European Rating Platform EU registered and authorised CRAs will have to communicate to ESMA all credit ratings they issue. ESMA will make them available to the public on a central website. Why did the Commission propose specific rules for sovereign ratings? Sovereign ratings include ratings of countries, regions and municipalities. Sovereign ratings are very important for the rated public entity. For instance, the conditions of access to external funding very much depend on the rating received. In addition, rating actions with regard to specific countries can have impacts on companies located in that country, on other countries and even on the stability of financial markets. Due to this specific role, it is particularly important that sovereign ratings are accurate and transparent so that investors can fully understand rating actions regarding sovereigns and their wider implications. Should there be a prohibition of sovereign debt ratings? Sovereign debt ratings are important and the implications of such ratings can in some circumstances be far-reaching. Not only do they affect the borrowing costs of Member States but they can also have further implications for other Member States and the financial stability of the Union as a whole. However, a prohibition of sovereign debt ratings could give the impression that Member States had something to hide and therefore it is not part of the new rules. A prohibition could have important effects for the access to capital of some Member States and could increase the borrowing cost for sovereign debt. The Commission considers that this Regulation improves considerably the transparency of sovereign ratings and will avoid negative effects of sovereign ratings which have been observed in recent years and stop risks of market disruption. To avoid market disruption, rating agencies will set up a calendar indicating when they will rate Member States. Such ratings will be limited to three per year for unsolicited sovereign ratings. Derogations remain possible in exceptional circumstances and subject to appropriate explanations. The ratings will only be published on Fridays after close of business and at least one hour before the opening of trading venues in the EU. Furthermore, investors and Member States will be informed of the underlying facts and assumptions on each rating which will facilitate a better understanding of credit ratings of Member States. Will the Commission set up a European Credit Rating Agency/Foundation? The Commission did not propose to set up a European credit rating agency. This analysis showed that setting up a credit rating agency with public money would be costly (approximately €300500 million over a period of 5 years), could raise concerns regarding the CRA’s credibility especially if a publicly funded CRA would rate the Member States which finance the CRA, and put private CRAs at a comparative disadvantage. However, as part of this new framework, the Commission will analyse the situation in the rating market and report to the European Parliament with regard to the feasibility of creditworthiness assessments of sovereign debt of EU Member States, a European credit rating agency dedicated to assessing the creditworthiness of Member States' sovereign debt and/or a European Credit Rating Foundation for all other ratings. Will there be rules allowing civil claims against credit rating agencies? Ratings are not mere opinions but have important consequences. Therefore, CRAs should operate responsibly. The regime does not aim to address "wrong ratings". Investors will only be able to sue a credit rating agency which, intentionally or with gross negligence, infringes the obligations set out in the CRA Regulation, thereby causing damage to investors. This new regime will ensure that rating agencies will act more responsibly as they can be held liable by investors and issuers. Will there be a reversal of burden of proof for civil claims? No, the new rules do not include such a reversal. However the Regulation ensures that the judge/competent court will need to take into consideration that the investor or issuer may not have access to information, which is purely within the sphere of the CRA. This new regime will ensure that rating agencies will act more responsibly as they can be held liable by investors and issuers. rotation rule - limited to resecuritisations A long relationship between a CRA and an issuer could undermine the independence of a CRA and in view of the issuer pays model lead to an important conflict of interest that could affect the quality of these ratings. To this end the rotation rule limits the duration between a CRA an issuer. While the Commission proposed a broader scope, the Regulation limits the rotation rule to re-securitisations. This can be seen as an important way to test the effectiveness of the rotation rule. By end 2016, the Commission will report back to the European Parliament on the effectiveness of the rotation rule with a view to extending the scope if appropriate. new European Rating Platform All ratings for EU registered and authorised rating agencies will be published on the central European Rating Platform, at the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), which will improve the visibility and comparability of credit ratings from debt instruments. The Platform will also contribute to the visibility of small and medium-sized credit rating agencies operating in the EU. Is deleting all references to ratings from EU legislation the best solution, i.e. the Dodd-Frank Act in the US? The Commission supports the view that sole and mechanistic reliance on the external credit ratings should be reduced. However, it is important that reducing overreliance on credit ratings does not lead to legal uncertainty. It would not be appropriate to remove all references to external ratings without considering alternative credit risk measures. The experience in the US has shown that it is difficult to remove references to ratings without having viable alternatives in place. The credit ratings should be considered as opinions amongst others. Furthermore, it is important that all financial entities conduct their own internal credit risk assessment, subject to supervision by the competent authorities. To this end, the Commission favours a twostep approach. First, the Commission will propose to remove all references which trigger mechanistic reliance on ratings, and in a second step, the Commission will report to the European Parliament on alternatives to external credit ratings with a view to removing all remaining references by 2020.