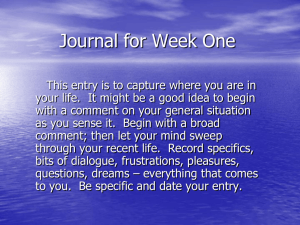

A_70_266_ENG - FreeAssembly.net

advertisement