2.3 why good governance is critical for the - NAP

advertisement

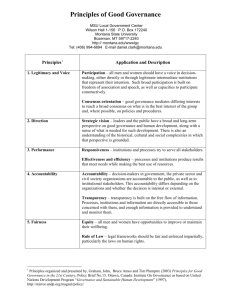

Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” 1.0 INTRODUCTION Through the legal obligations to “respect,” “protect,” and “fulfill” the right to health, governments have implicit duties to ensure that health services are provided effectively to their populations (CESCR, 2000). One of the biggest threats to the right to health is a lack of good governance in the health system, which limits the ability of the health system to fulfill its essential functions, and can create opportunities for corruption. If there is a lack of concern for basic governance principles in health care delivery, health care resources may have no impact on the intended end user. Poor governance and corruption thus undermine health care delivery by reducing the availability of resources and access to health care. This places the heaviest burden on the poor and marginalized (Lewis, 2006). Corruption has been defined as the abuse of public roles and resources or the use of illegitimate forms of political influence by public or private parties (Johnston, 1997). The World Bank identifies corruption as the single greatest obstacle to economic and social development. Corrupt practices in the health system can have a threefold impact: 1) an economic impact - when large amounts of public funds are wasted; 2) a health impact - as the waste of public resources reduces the government's capacity to provide good quality services and products, patients may turn to unsafe medical products available on the market instead of seeking health services, leading to poor health outcomes for the population; and 3) a government image and trust impact - as inefficiency and lack of transparency reduce public institutions' credibility, this decreases donor's trust in the capacity of the government to deliver on promises and lowers investments in such countries. This happened in Zambia when large-scale corruption by government officials resulted in a major withdraw of health-aid for the country by donors (Pereira, 2009). Each year, an estimated US$ 4.1 trillion is spent worldwide on providing health services but a significant amount of this money does not reach its intended beneficiaries (Transparency International, 2006). As one example, in the area of procurement alone, it is estimated that between 10% and 25% of global spending on public procurement in the health system is lost to corruption (Transparency International, 2006). In recent years, the issue of corruption and the development of public policy to mitigate the effects of corruption have gained importance globally. For instance, the United Nations (UN) Convention against Corruption was adopted by the UN General Assembly in October 2003 and came into force in 2005, and raised the importance of fighting corruption worldwide. In 2009, the UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon even highlighted the impact of corruption on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). He publicly stated that corruption can kill development and may very well impede efforts to achieve the MDGs (UN, 2009). While corruption is difficult to eradicate, good governance can certainly reduce its manifestation. Despite its importance, there are few examples of how to incorporate good governance in health system strengthening (Brinkerhoff et al, 2009). Good governance is defined as “the exercise of economic, political, and administrative authority to manage a country’s affairs at all levels, comprising the mechanisms, processes, and institutions through which that authority is directed. Good governance is, among other things, participatory, transparent, accountable, and efficient. It promotes the rule of law and equal justice under the law. It requires the involvement of the private system, civil society and the state and is a prerequisite for sustainable human development” (UNDP, 1997). Good governance in the health care system is instrumental in helping to lessen the likelihood of corruption taking place. Still, there are few studies that explicitly examine what the obstacles are to good governance in the health care system and how to incorporate good governance effectively. We hope our study can help fill the void in this area. The rationale for focusing our research grant on good governance and not on corruption is also practical. We argue that in the absence of good governance, corruption may take place. The topic of corruption often makes policymakers and health professionals uncomfortable. As a result, this can lead to decreased access to information as key informants may not respond to requests for interviews. Furthermore, when they do agree to be interviewed, corruption as a core interview topic is difficult and oftentimes challenging for key informants to communicate Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” freely about, out of fear that they may implicate themself or a colleague and potentially incur negative consequences. This grant thus focuses on good governance as a means to probe for the potential for corruption in the pharmaceutical system and to identify the different forms and locations of corruption in the pharmaceutical system (i.e. kickback schemes from procurement or extortion for access to services). This grant is also in line with the Principal Investigator’s current proposal, supported by the World Health Organization (WHO), to establish a “WHO Collaborating Center on Good Governance and Transparency in the Pharmaceutical System” at the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto. 2.0 JUSTIFICATION FOR THE PROPOSED RESEARCH PROJECT 2.1 RATIONALE FOR SELECTION OF BRAZIL AS THE CASE STUDY We will examine the issue of good governance (Figure 1) in health more narrowly through the pharmaceutical system and in the country context of Brazil. Pharmaceuticals are key inputs into the health sector and as we will explain below, without good governance in place, the pharmaceutical system is potentially vulnerable to corruption. We selected Brazil as the case study for a number of reasons. First, Brazil has the largest pharmaceutical market in Latin America and has been a leader in terms of global pharmaceutical policies promoting access of medicines for its population. Brazil has a large and diverse population of about 191 million people (IBGE, Brazilian Statistics Institute, 2010), and although it is a middle-income country, acute socio-economic disparities exist amongst its population. For instance, the three poorest Brazilian states (Piaui, Paraiba and Alagoas) have a high percentage of families living with less than half of the minimum salary per month, which equates to 44.1%, 42.2% and 47.6% of the state population, respectively (IBGE, 2010).The per capita consumption of medicines in Brazil is approximately US $51 per year; however, almost half the medicines are consumed by 15% of the population, who represent the wealthiest segment of society (Cohen, 2006). This is despite the fact that Brazil has domestic policy priorities to ensure access to essential medicines, and this has led to the construction of various laws, regulations and policies to ensure good governance in the pharmaceutical system. Secondly, Brazil has both a public and private domestic pharmaceutical industry which provides medicines to its public health care system the “Sistema Único de Saúde” (SUS). Brazil’s pharmaceutical system is particularly rich for the study of good governance because all three government levels - federal, state, and municipal have diverse responsibilities regarding the delivery of medicines to the population, and therefore are required to cooperate with each other. For example, municipalities collect revenues for health care but may also rely on the Federal Government for discretionary fiscal transfers. Moreover, our project is consistent with the goals of the Government of Canada, which through CIDA has supported efforts to reform the social and public sectors and achieve greater equity in Brazil. Finally, Transparency International ranked Brazil in 2010 as a country that likely has high institutional corruption (Transparency International, 2010), thus suggesting that we may indeed find areas where good governance is lacking and corruption is thriving in the pharmaceutical system. Brazil is a vast country with rich differences economically, socially and geographically. Given this, we will seek to probe the good governance (or lack thereof) of pharmaceutical systems in two Brazilian states with different socio-economic contexts, the State of Sao Paulo (one of the wealthiest in Brazil) and the State of Paraiba (one of the poorest states in Brazil). For sure, our case study products are clearly restricted explorations of Brazil. However, we aim to prepare our studies so that they ideally yield results that are more generally applicable. 2.2 RATIONALE FOR EXAMINING CORRUPTION RISKS AND GOOD GOVERNANCE IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL SYSTEM While most rich countries spend at least 5% of GDP on health, most developing countries spend less than half of this figure. Insufficient health budgets and the added challenge of the HIV/AIDS epidemic has led to a general shortage of drugs, medical supplies, health care workers, and a reduction in their salaries. This has resulted in a deterioration of general health. Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” While it is true that lack of governance in the health system is a concern everywhere, developing countries with already scarce public resources, and oftentimes weak institutions, are particularly vulnerable to the effects of poor governance. Weak governance in the health care system exacerbates many existing challenges health systems face and can create new ones for governments and patients. It increases costs, decreases the effectiveness and volume of health care services and reduces resources, as some examples. Weak or non-existent rules and regulations, as well as over-regulation, lack of accountability, low salaries and limited offer of services (i.e. more demand than supply) are among the key manifestations of poor governance in the health system. It is a reflection of the structural challenges in the health care system as well as where it takes place within the system. The scale of corruption also varies: it can be a direct result from state capture which is often linked with political corruption; it may be petty, for instance, at the implementation level where the public interacts with public officials, such as surplus payment demands from health professionals; or grand (i.e. fraud and procurement abuse). Weak or no governance in the pharmaceutical system creates opportunities for corruption and results in additional barriers to drug access. Poor drug access continues to be one of the key public health problems of today (Kohler and Baghdadi-Sabeti, 2011). There are approximately 2 billion people, or one-third of the global population, who lack regular access to medicines (Baghdadi et al, 2008). The WHO estimates that by improving access to existing essential medicines (and vaccines) about 10 million lives could be saved per year (WHO, 2004a). Global inequalities in access to pharmaceuticals are caused by a number of variables including poverty, high drug prices, poor health infrastructure, insufficient health expenditure and corruption. But until recently, the latter was often overlooked. Fortunately, there is growing recognition among policy makers that the pharmaceutical system can waste valuable resources allocated to pharmaceutical products and services, and denies those most in need of life-saving or lifeenhancing medicines. Global organizations, including the WHO and the World Bank are thus addressing the issue of lack of governance in the pharmaceutical system globally. This is encouraging news for improving drug access for the global poor who are most vulnerable as they are forced to make sub-optimal choices that include: purchasing less expensive drugs from unqualified or illegal drug sellers distributing counterfeit or sub-standard drugs; not taking needed medicines if they are unavailable in the public health system; or impoverishing themselves by having to purchase expensive drugs in the private health system (Niens et al, 2010). 2.3 WHY GOOD GOVERNANCE IS CRITICAL FOR THE PHARMACEUTICAL SYSTEM The pharmaceutical system is susceptible to corruption if good governance is not in place for a number of reasons. One, the sale of pharmaceutical products is lucrative, the more so because the final customers (patients and their families) are more vulnerable to opportunism than in many other product markets. This is due to information gaps and often very inelastic demand. Pharmaceutical suppliers typically are “profit-maximizers” and will choose to behave in ways that maximize their interests. There is nothing inherently wrong with profit maximization so long as it is not counter to the public interest. However, as scandals such as the Vioxx case illuminate, pharmaceutical suppliers have in the past disregarded public interest for financial gains. The second reason why the pharmaceutical system is susceptible to corruption is that it is subject to a significant degree of government regulation, such that if there are not appropriate checks in place, government officials may have a monopoly on several core decision points in the pharmaceutical supply chain, and also have some discretion in making regulatory decisions. Government intervention is essential in the pharmaceutical system given the imperfect nature of the market and the need to improve the efficiency of resource allocation. Also, regulation is rationalised on the grounds of protecting human life and public health by ensuring that only safe and efficacious medicines are made available in the market. But if there is state capture and Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” poor institutional checks on individual discretion, the public interest may be jeopardized. For instance, governments usually determine what drugs are included on a national essential drugs list or reimbursement list of a public health care payer. The inclusion of a drug on such a list, particularly a reimbursement list, can mean significant financial income for a drug manufacturer as it guarantees the product a relatively predictable market share. If there is a lack of oversight, regulators may be able to make discretionary decisions about what drugs should be selected based on individual gain and not on the public good. The third reason why the pharmaceutical system is a ‘breeding ground” for weak governance is because it often is difficult to distinguish authentic pharmaceutical products from counterfeit ones. In many countries with weak regulation and enforcement of drug distribution standards, the sale of counterfeit, unregistered or expired drugs are very common. The WHO estimates that about 25% of drugs consumed in poor countries are counterfeit or substandard (WHO, 2003). It is very difficult to control such practices particularly where patients and even health professionals are not able to differentiate between legitimate and fake drugs. Counterfeiters are often very skilful at copying the form, colour, trademarks and packaging of legitimate products. While in many markets patients tend to have more confidence in recognized foreign produced drugs, the high prices for the legitimate versions of these relative to purchasing power drives many consumers to seek lower cost alternatives, which in many cases are not legal, safe or reliable. These actions have had significant social costs both in terms of access to drugs, particularly for the poor, but also in terms of the quality and safety of the drug supply. In addition, the likelihood of developing resistance to sub-standard and/or counterfeit antibiotics is elevated, which can result in huge health costs. It is only when there is blatant sloppiness in copying that patients and health care providers are able to identify counterfeit medicines. Government commitment to better governance in the system is vital particularly in low and middleincome countries, where it is estimated that over 70% of all pharmaceutical purchases are paid for out of pocket (WHO, 2004b) and represent the largest household health expenditure (WHO, 1998). 3.0 RESEARCH MOVTIVATION AND CONTRIBUTION TO THE LITERATURE In recent years, a number of studies such as: Kohler (2011) Vian, Savedoff and Mathisen (2010), Lewis and Pettersson (2009); Vian (2008).; Cohen-Kohler et al. (2007); Lewis (2006); and Di Tella and Savedoff (2001) have examined health and corruption and have begun to provide examples of what strategies work best to enforce good governance and lessen the likelihood of corruption. All of the studies have pointed out that corruption has an impact on equity by limiting access of the poor to the health care system. Several quantitative and qualitative studies have illustrated how the burden of corruption impacts the poor more heavily given their limited ability to pay. The poor and marginalized can be denied access to necessary care if payments are required for health care services (Lewis, 2000). For example, in Bulgaria, high income urbanized patients were more likely to make informal payments and thus receive care they needed in contrast to the low-income population (Balabanova, 1999 cited in Lewis, 2000). A study by Amnesty International on maternal health in Burkina Faso found that corruption by health professionals is one of the primary causes of death of thousands of women during pregnancy. Poor women may not get critical health care services simply because they are unable to pay informal fees (Amnesty International, 2010). Further evidence comes from the International Monetary Fund which demonstrated that corruption has a significant, negative effect on health indicators such as infant and child mortality, even after adjusting for income, female education, health spending, and level of urbanization (Gupta et al., 2000). Corruption lowers the immunization rate of children, can prevent patient treatment, particularly for the poor, and discourages the use of public health clinics (Azfar and Gurgur, 2005). The bottom line is that corruption affects the ability of the poor to access essentiall health services. We need to gain more knowledge about the causes and consequences of corruption in the health system and what interventions work best to minimize it. 4.0 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” We aim to achieve four major goals related to good governance in the pharmaceutical system: 1. Examine good governance characteristics (consensus oriented, accountable, transparent, responsive, equitable and inclusive, effective and efficient, follows the rule of law, participatory - as per Figure 1 below) throughout the key “decision points” in the pharmaceutical system. Based on the conceptual framework illustrated in Figure 1 we will examine issues such as do patients have to pay surplus charges for publicly funded pharmaceutical services? Are medicines unavailable in public health systems because they have been diverted to the private system? Are drug formulary decisions participatory? 2. Identify the factors that facilitate or impede the presence of good governance in the pharmaceutical system. We will seek to understand what factors facilitate or impede good governance in core areas such as budget planning, procurement, regulation, and drug egistration. 3. Compare and contrast good governance in the pharmaceutical system between states and among different levels of government. There is a lack of rich comparison in the literature on good governance in the health system between different socioeconomic contexts. This research hopes to uncover what socio-economic factors (if any) may contribute more to the presence of good governance. Given Brazil’s diversity in socio-economic conditions, particularly between states, it is an ideal study site for this objective. We will focus on the State of Sao Paulo and the State of Paraiba. 4. Determine what interventions best support policy change that can strengthen good governance in the pharmaceutical system. For example, the public posting of medical supply prices can help prevent collusion between suppliers, there is evidence that regular external and internal audits can help ensure budgets are being spent appropriately, and citizen scorecards can help decision makers identify where potential problems lie. Ideally our findings from our case studies will be generalizable to other contexts. 5.0 RESEARCH PLAN 5.1 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK We will examine the following characteristics of good governance in key decision points of the pharmaceutical system: Figure 1. Characteristics of Good Governance (UNESCAP, 2012) The above characteristics will be examined throughout the pharmaceutical system. To do this, we will use (1) case studies; (2) key informant interviews with public officials, health professionals, patients international organization and industry representatives, and (3) analysis of legislation, regulations, government reports, policy documents and commentary, and academic literature to corroborate data provided during key informant interviews. 5.2 METHODOLOGY Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” Pursuant to the main research objectives of the project, four methodological approaches will be used to dentify key factors that are integral to both the optimal usage of the legislation, policy and regulations: 1) Historical analysis of political processes and actors that have informed the design and contentof the legislation, policy and regulation relevant to good governance in the pharmaceutical system at the federal level. 2) Present-day descriptive case studies on good governance in the pharmaceutical system through the lens of the role of the federal, state and municipal governments in: a. The State of Sao Paulo; b. The State of Paraiba. 3) Analysis of political, economic and socio-cultural factors that impact the present and future viability of the legislation, policy and regulation required for pharmaceutical system good governance. 4) Comprehensive legislative/policy reviews relevant to good governance in the pharmaceutical system. 1) Historical analysis of political processes and actors An historical approach involving an inquiry into the political process and the key actors surrounding the formation of the legislation, policy and regulations will take place. This, in turn, will aid in the understanding of the political forces and climate that gave rise to the various laws relevant to good governance in the pharmaceutical system. Specifically, we will examine the positions and roles of key political actors, interest groups and generic and patent-protected pharmaceutical industry members that have informed the law. Contextual factors such as the availability of financial and institutional resources will also be examined. 2) Present-day descriptive case studies Case study research and analysis is characterized as an empirical enquiry used for qualitative, in-depth analysis identified in a limited, contemporary context such as a national policy application, and in studies where the researcher has little or no control of the events to be analyzed. Case studies have been the preferred strategy used by economists, political scientists and social researchers as it provides greater flexibility when observing and identifying research variables. Critics of this research method have identified limitations to the investigative process, pointing out that small numbers of cases offer no grounds for establishing reliable, general findings, and that investigators may encounter biases in particular responses which can influence the study’s final results. However, this particular research method can be justified as the most appropriate for this research program because the particular study objectives require the flexibility allowed only through the case study research method, as opposed to the use of other methods, such as historical analysis and general survey research mechanisms. The data collection and analysis that will be derived from the use of this case study sampling technique will help yield findings that are high quality detailed descriptions about each case, rather than empirical generalizations, which would be captured by a randomized sampling approach. In using a case study method there is an acknowledged potential of collecting biased data, thus all results will be triangulated with a variety of data sources and techniques to identify the diverse characteristics and central themes that emerge within this case and to reduce the impact of bias on the research sample. We will seek to probe the good governance (or lack thereof) of pharmaceutical systems in two Brazilian states with different socio-economic contexts, the State of Sao Paulo (one of the wealthiest states in Brazil) and the State of Pariaba (one of the poorest states in Brazil). Here, we will examine indicators of good governance in key areas of the pharmaceutical supply system that will include but not be limited to the following points in the pharmaceutical system: Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” a) Public expenditure management: including budgeting, planning, budget execution, monitoring and tracking. This is a key focus given that much public monies are typically wasted due to corruption and improper information systems. There are already well known tools in place which can be applied to build up transparency and accountability, such as the Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) framework and the Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys (PETS). b) Public procurement: including linkages to budgeting and regulations. Public procur ement is commonly susceptible to corruption if good governance is not in place. The focus on procurement needs to be comprehensive and include an examination of all stages of the process, including quantification of need/demand, budget allocation, supplier payment, acceptance of shipments and distribution to end users. c) Drug distribution and logistics: Poor storage conditions can lead to losses either through the mismanagement of pharmaceuticals (leading to their expiration) or plain corruption (theft of medicines). Shipments can be stolen at many points in the delivery system including by port personnel, crime syndicates that organize large-scale thefts from warehouses, and by drivers along the delivery route. Even if drugs reach their intended destination, government officials and health facility workers may steal drugs for their own use or profit. Incentives for diversion may be more of a risk in the distribution and storage of expensive medicines such as anti-retroviral drugs. Here we will examine how drugs are delivered from the manufacturer to the end user. d) Drug regulatory governance: Often drug regulatory agencies are poorly funded with limited staff and institutional capacity. If the legislative and regulatory environment is weak and there is a lack of transparency and accountability in the processes, suppliers may pay off government officials to register their drugs without the requisite information. In other cases, government officials may deliberately delay the registration process to solicit a bribe or to favour another supplier. Questions for the above subjects and more areas will be based on the WHO Measuring Transparency in the Public Pharmaceutical System Assessment Instrument (Baghdadi et al, 2008) which the Principal Investigator assisted in developing and has had experience applying in Costa Rica and Bulgaria (See Appendix I). 3) Analysis of contextual factors that may impact good governance This analysis will identify the contextual factors that impede or facilitate good governance in Brazil’s pharmaceutical system and inform policy recommendations to better facilitate access to medicines. General contextual factors, such as international human rights treaties and other institutions, regulations, political environment, and economy will be examined. 4) Substantive and procedural legislative/policy review How current laws (domestic and international) and accompanying provisions and regulations are implemented will be evaluated. This will provide an understanding of the strength of the legislation that is designed to support good governance in the pharmaceutical system. Our focus will primarily be at the federal level and will include, but not be limited to, a review of the management contract (contrato de gestão) between the Brazilian Ministry of Health and the National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA), designed to measure the performance of ANVISA (ANVISA, 2006). We will also explore Brazil’s ratification of international and regional human rights treaties and the extent to which these are reflected in domestic legislation. More specifically, our work will entail the following: 1. Substantive Review A focus on the substantive aspects of the good governance law will seek to uncover areas of ambiguous language in the legislation, unnecessary complications and restrictions, and to identify areas that are effective. Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” 2. Procedural Review In addition to the substantive scope of the bill, we will examine the procedural aspects of the laws, such as timelines for amendments, appeal processes, and availability and impact of infrastructural support required to make use of legislation. 3. Impact Analysis A general impact analysis of the relevant legislation, policy and regulations will further illustrate their practical viability. This analysis will investigate: o A survey of the various procedural and practical costs that are required or anticipated on the part of using legislation, policy and regulations relevant to good governance; o The presence of procedural incentives and disincentives to make use of the above; and, o The bureaucratic path required. We will also investigate processes related to public consultations on pharmaceutical issues, public hearings that aim to ensure a transparent and democratic process for the entire population in health policy (ANVISA, 2003) and how well the role of ombudsmen works in areas relevant to good governance in the pharmaceutical system. 5.3 FORMULATION OF CONSTRUCTIVE POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS Recommendations for improvements to the good governance in the pharmaceutical system will build upon the preceding analysis of historical, present and future contextual factors, legislation and policy, as well as an understanding of the practical realities to realizing good governance. The study will highlight not only past and present day barriers, but will attempt to anticipate future threats to the viability of it. Areas such as unclear language and procedural impediments will be identified with a view to addressing flaws in the legislation. Also, the information gathered from our research will illuminate deficiencies in good governance, whether they exist in governmental infrastructure, financial and human resources or sheer lack of effort and interest. We have unique access to key data sources through our partners in Brazil and the Principal Investigator’s contacts at the World Bank and WHO. 5.4 DATA SOURCES The assembled research team has unique access to key data sources including access to global institutions, government policy makers and their relevant documentation. The team is deeply familiar and authored in the relevant pharmaceutical policy, good governance/corruption, and legal literature and intimately networked with the WHO Essential Medicines and Other Drugs Department. The prior policy, management and research experience of team members at the World Bank, WHO and UNDP will bear positively on the complexity of this study. Case studies based in the States of Sao Paulo and Paraiba Policy documentation and commentary Legislation, amendments, regulations Academic literature Key informant interviews Our main data sources will be the case studies that examine good governance in the pharmaceutical system in the context of the States of Sao Paulo and Paraiba and key informant interviews. Relevant academic literature from the disciplines of political science, law, economics, medicine and the social sciences will be used to incorporate fundamental perspectives, principles and approaches in our understanding of key issues surrounding drug Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” access and legislation. We will closely examine relevant policy documentation and commentary, in addition to laws, policies and regulations from Brazil.Interviews with key stakeholders, informants and other experts will provide additional insight into the design and utility of the legislation and policy. Key Informant Interviews In-depth, qualitative key informant interviews of a purposive sample of approximately 40-50 persons at all levels of government (municipal, state and federal), chosen for their first-hand knowledge about of relevant subject matter germane to the good governance of Brazil’s pharmaceutical system, will be conducted. The interviews will be loosely structured. This method is advantageous in that it provides information directly from knowledgeable persons; it provides flexibility to explore new ideas rather than structuring the informants’ responses in terms of the researchers’ hypotheses; and such interviews are inexpensive to conduct (USAID, 1996). Limitations are that they may be biased if key informants are not chosen carefully, their findings may be difficult to validate, and the interviewer’s biases can affect the outcomes. Findings from these interviews will be triangulated with additional data to help corroborate or reject findings. Limitations are that they may be biased if key informants are not chosen carefully, their findings may be vague, difficult to validate, and the interviewer’s biases can affect the outcomes. Some potential key informants in Brazil are: a. Federal/State Public Health Officials: Public health officials will be targeted for key informant interviews in Brazil. The purpose of these interviews will be to obtain information on their perceptions on public policies, legal instruments relevant to pharmaceutical good governance. Possible informants include: Rocha Santos Padilha (Minister of Health); Paulo Gadelha (Director of Fiocruz Foundation); Hayne Felipe da Silva, (Director, Farmanguinhos/Fiocruz), Jorge Bermudez (Fiocruz), Carlos Morel (Fiocruz), José Carvalheiro (Sao Paulo Health Institute and Fiocruz); Dirceu Grecco (Director of Brazilian National Program on STD/HIV); Dirceu Raposo de Mello (National Health Surveillance Agency ANVISA) and; Aloizio Mercadante, (Minister of Science, Technology and Innovation). b. Global Institutions: We will approach health policy advisers from the Pan American Health Organization (James Fitzgerald, Coordinator of the Strategic Fund), the World Bank (Armin Fidler, Director of Health and Nutrition), WHO (Guitelle Baghdadi-Sabeti, Strategic Adviser) as well as the Inter-American Development Bank (Andre Medici, Senior Health Economist in the Social Development Division). The purpose of these interviews is to learn how these international organizations approach health policy and work to guarantee good governance, transparency and accountability and consequently equity in health. c. Health Professionals and Patients: Doctors, nurses and pharmacists working in both rural and urban environments will be targeted for key informant interviews. Interviewing health professionals who are delivering the services and products to the populations is critical to the project in terms of understanding where potential areas of weakness may exist in a given health system. Key informants will be identified through various associations and also through snowball technique. Patients will also be targeted at different points in the health care system (i.e. primary and secondary care) so we can learn about their perceptions of good governance in the pharmaceutical system. d. Pharmaceutical and Medical Supply Industry Representatives: Interviews with both domestic and international pharmaceutical industry (both generic and research-based) representatives will be conducted to understand how the private system interacts with the public health system in Brazil and what challenges good governance in the system. We will also interview key procurement officers and medical stores personnel. Key informants will include: Eloi Domingues Bosio (President – Interfarma, Brazilian Pharma Association) and Adriana Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” Diaféria (Legal Director, Farmabrasilis – Brazilian Association of National Pharmaceutical Industry). e. Civil Society Representatives: We will contact with key informants from civil society to probe their views on pharmaceutical system governance. Potential key informants include: Eric Stobbaerts (Head, Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi)-Latin America), Gabriela Chaves (Doctors Without Borders, MSF-Brazil), Renata Reis (Brazilian Interdisciplinary Agency of AIDS – “Agência Brasileira Interdisciplinar de AIDS” - ABIA), Regina Lancelloti (President, Support Group for People with Hepatitis C) and Lucia Nader (Director, Conectas Human Rights). All key informant interview participants will be initially approached through an invitation letter explaining the purpose of the study. Follow up calls will be made so a critical mass of participants is guaranteed. The interviews will be semi-structured and open-ended and will be based on a list of key issues, such as the key informants perceptions and behaviors surrounding public health policies, legal instruments and practices coming from different actors related with the pharmaceutical public health care system that can guarantee transparency, accountability and good governance, and as well how citizens and other actors are aware of the problems and needs under this system, and their willingness to endorse policy reforms that address these measures. This research presents minimum risks. Key informant interviews will be advantageous for this study as they will provide information directly from knowledgeable persons, flexibility to explore new ideas and they are inexpensive to conduct. The questions comprising the key informant interview guides will be tailored to be appropriate to each interviewee’s context. 5.5 DATA ANALYSIS Key informant interviews will be recorded and transcribed for data analysis. Transcripts will be subject to the application of content analysis (Berg, 1995; Strauss and Corbin, 1994; Holstein and Gubrium, 1994), which will require the following steps. A first reading will be undertaken to develop an understanding of the major issues identified. Second, more readings will be carried out to generate a list of themes and issues that is as complete as possible. Third, a systematic coding frame will be developed, rearranging the data to fit systematically into themes. This will involve synthesizing the data and abstracting from it. The next step will involve one or more readings to apply the coded themes. A final reading will be undertaken to ensure that there are no missing issues that need to be addressed. Finally, the data will be mapped and interpreted using the codes to map the extent and type of phenomena and find associations between themes with a view to provide explanations. The data from Brazil will be translated from Portuguese into English, when necessary, and the qualitative software programme, NVivo, will be used to analyze all data. Document Analysis Reports from global institutions, domestic pharmaceutical legislation and regulations, annual reports from the federal, state, and municipal levels of government as well as health services officials will be collected and compared. This phase in the methodology will provide a cross check of evaluations between the perspectives of different key informants; this is known as the “triangularization” of data, a process often used in the case study research method when multiple sources of evidence are analyzed. 6.0 FEASIBILITY OF ACHIEVING PROJECT GOALS Brazil is a complex, large country so we are necessarily focusing our grant on a limited number of states. We have selected states with vastly different socio-economic conditions as a means to initiate an examination of the issue of good governance in the pharmaceutical system. We know these states are not the “universe” of Brazil but they will provide us with some good preliminary data on pharmaceutical good governance. We also recognize that good governance may be a topic that is difficult to probe given its association with corruption. Still, the feasibility of Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” achieving the goals of the project is strong. One, the Principal Investigator has spent over a decade devoted to both operational and theoretical research in the area of health and corruption so she is familiar with the literature and has operational experience specific to good governance in the pharmaceutical system. As such, she has an understanding of what obstacles may present themselves when probing the issues and by diversifying key informants, knows how to ensure adequate information collection. Second, the Principal Investigator has a working knowledge of the Portuguese language and is knowledgeable about Brazil’s culture, health care system and politics given her prior field work on Brazil’s pharmaceutical system for the World Bank over the course of four years. Three, the Principal Investigator has spent over twenty years conducting key informant interviews with individuals involved in the health area in countries all over the world (for the World Bank, consultant for various international organizations, and research as an academic) so is familiar with how to organize interviews, overcome potential obstacles as well as to use the data effectively. Fourth, the Principal Investigator has a good network of contacts thanks to her prior work at the World Bank, WHO, UNDP and PAHO. Fifth, the project is one of the core research areas of the Principal Investigator who has spent the past ten years working on the topic of corruption and health. Lastly, through the collaboration of partners in Brazil at the University of Sao Paulo and at the NGO, Universities Allied for Essential Medicines, we will have access to key informants and key documents from Brazil. The Principal Investigator will also be assisted by her Co-Investigators, Warren Kaplan, PhD, MPH, Esq and Lisa Forman. LLB, MA, SJD. Both have experience globally working on issues related to pharmaceutical policy and have legal training. Dr. Kaplan is an attorney, specializing in intellectual property, licensing, contracts and business law, has extensive consulting experience in the pharmaceutical sector, and has also worked recently in the private and public sectors on generic medicines policies. Dr. Forman is a legal scholar whose work focuses on the relationship between international human rights law and trade-related intellectual property rights in relation to access to medicines in low and middle income countries. Drs. Kaplan and Forman will assist in the literature review and analysis of treaties, legislation, policy and statutory documents. Finally, through the collaboration of Karen Hussmann, a global expert in health and corruption policy, who has worked extensively with the UNDP in the implementation of good governance in health projects, we will ensure that our project methods and findings are sound and operationalized effectively. She will also help us access relevant data from the UNDP, which is the lead UN institution on the issue of good governance. 7.0 DISSEMINATION OF FINDINGS Research will be presented as it progresses in many forms. We will develop a series of draft working papers and as they are refined they will be presented for critique in academic settings, as opportunities allow. Likely Canadian venues include the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy and Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, and the annual conference of the Canadian Society for International Health. International venues will also be pursued for critique of research as opportunities arise (i.e. IDB, World Bank and WHO seminars). The Principal Investigator will seek formal publication of research findings in peer-reviewed scholarly journals (i.e. Health Policy and Planning, International Journal of Health Services, The Lancet, The CMAJ, and Globalization and Health). She also plans to publish findings in the media, where appropriate. 8.0 SIGNIFICANCE This research provides much needed inquiry into a relatively new area in health policy - what is good governance of the health system, how does it manifest itself and what is its impact on practice – and hopes to explore examples which can illuminate the opportunities/barriers to good governance specifically in the pharmaceutical system. Based on the findings from the research, we hope to craft policy recommendations about what interventions will work best and longest to maximize good governance and reduce the risk of corruption. There is a need for rigorous academic research to examine its actual or potential impact on public health particularly for the poorest. This research is in keeping with CIHR’s strategic focus on health Jillian Clare Kohler, Research Proposal “Evaluating Governance, Accountability and Transparency in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical System” and equity as an absence of good governance, coupled with poor corruption controls can lead to corruption in the health system, denying the most vulnerable to core health care services. Lessons learned from this project will be of interest to policymakers, health professionals and the private sector globally, particularly as there is a growing interest in the global development community on how to improve governance in the health system and ensure development assistance is spent effectively and responsibly. 9.0 TIMELINE Activity Projected Timelines Literature review, data and document collection (legislation, policy, regulations); concurrent document analysis. September 2012 – September 2013 Develop data collection tools (interview questions), consent forms, apply for ethics, schedule and coordinate key informant interviews. September 2012 – December 2013 Key Informant Interviews and Policy Framework Development; concurrent interview transcription and analysis, document collection and analysis. Jan 2013 – May 2015 Final analysis, development of policy recommendations, manuscript preparation. June 2015 – June 2016 Dissemination Ongoing from September 2013 to 1 year 14 months 16 months 1 year – September 2016