Cell Tech Communications Pty Ltd v. Nokia Mobile

advertisement

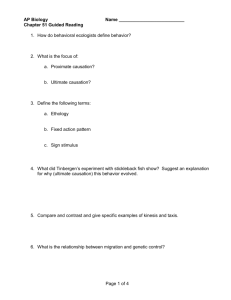

Queensland Bar Association Sections 11 and 12 of the Civil Liability Act 2003 - Causation Kevin Holyoak Sir Harry Gibbs Chambers Commencement and Application • • • Sections 11 and 12 commenced on 2 December 2002: subsection 2(1) of the CLA The sections apply to “any civil claim for damages for harm”: subsection 4(1). Schedule 2 to the CLA defines “harm” to mean “harm of any kind” and it is not limited to personal injury. It includes damage to property and economic loss The sections apply in relation to a “breach of duty”. Schedule 2 of the CLA defines “duty” as one “in tort”, or “under a contract that is co-extensive with a duty of care in tort” or “another duty under statute or otherwise that is concurrent with” such a tortious or contractual duty. 2 • The term “duty of care” is defined in schedule 2 of the CLA as “a duty to take reasonable care and exercise reasonable skill (or both duties)”. Consequently, the sections will not apply to strict or absolute promises. Further, this is subject to the provisions of any contract between the parties: subsection 7(3) of the CLA The CLA regulation of causation therefore has a tortious focus. In any event, there is authority in Queensland that “in reality causation in a commercial contractual context seems no different from causation in negligence” (Coley v. Nominal Defendant [2004] 1 Qd R 239 at paragraph [16] per McMurdo P, with whom Jerrard JA agreed) 3 Section 11 of the CLA • • Subsection 11(1) divides the causal inquiry into two elements:(a) factual causation; (b) scope of liability Subsections 11(2) and 11(3) further regulate “factual causation”. Subsection 11(4) further regulates “scope of liability” 4 • • Section 11 adopts recommendation 29 of the “Ipp” report, Review of the law of negligence report, 2 October 2002 – paragraph [7.25]-[7.51]. The report accepted the existing law (for example as listed in Wallaby Grip (BAE) v. Macleay Area Health Service (1998) 17 NSWCCR 355; BC9806780) but opined there ought be established in a statutory template a suitable framework to resolve individual cases and to preclude a Plaintiff from giving evidence as to what, hypothetically, would have been done had the duty of care been discharged. This was to counteract “hindsight bias” (Ipp report [7.40]) Section 11 regulates existing and developing law and is not a code: subsection 7(5) of the CLA. 5 Common law principles • Subsection 11(1) provides a bifarcal test. The High Court authorities held that the conception of “causation” is not susceptible of reduction to a satisfactory formula (per Dixon CJ, Fullagher and Kitto JJ in Fitzgerald v. Penn (1954) 91 CLR 268 at 277, adopted by Mason CJ, (with whom Gaudron J agreed) in March v. E & M H Stramere Pty Ltd (1991) 171 CLR 506 at 515) and that there is only one compound enquiry with the scope of liability or normative enquiry also playing a role in the assessment of fact (Travel Compensation Fund v. Tambree (2005) 224 CLR 627 at [81] per Callinan J) 6 • • Section 11 is an endeavour to reduce causation to a formula, adopting the twin divisional enquiry favoured in some intermediate appellate Court authorities (see for example Mahoney JA in Barnes v. Hay (1988) 12 NSWLR 337, 353; Petrou v. Hatigeorgiou (1991) Aust Torts Reports 81-071, at 68,566; Ruddock v. Taylor (2003) 58 NSWLR 269 at [85]-[89] – overturned in the High Court but on different grounds; cf Lisle v. Brice [2002] 2 Qd R 168 at paragraphs [24]-[29]) Attempts have been made to list the common law principles (Wallaby Grip (BAE) v. Macleay Area Health Service (infra); Tabet v. Mansour [2007] NSWSC 36) 7 Factual causation • • The Plaintiff must establish, on the balance of probabilities, that the Defendant’s breach caused, or materially contributed to, the harm (Bonnington Castings Ltd v. Wardlaw [1956] AC 610) Causation as a question of fact must be determined by applying common sense to the facts of each particular case (March v. E & M H Stramere at 515). Foreseeability is not a test of causation (Chapman v. Hearse (1961) 106 CLR 112) 8 • There is a positive aspect and a negative aspect to causation (for example, see the treatment of the question of causation by Jerrard JA, with whom the other members of the Court agreed, in Calvert v. Mayne Nickless Ltd (No. 1) [2006] 1 Qd R 106 at [90]-[99]) • The positive aspect requires there to be evidence from which it may be fairly inferred, as a probability, that the accident resulted from some want of care on the part of the Defendant (Davis v. Bunn (1936) 56 CLR 246, 255) 9 • • The negative aspect requires consideration of whether the step which ought to have been taken would have made a difference and the extent to which it would have made a difference (for example Greg v. Scott [2005] 2 AC 176 at 203 at [106]) “it is axiomatic that the wrongdoer is not liable for any loss, injury or damage that would have happened anyway”). This is the most appropriate use of the “but for” test (March v. E & M H Stramere Pty Ltd (infra)) A contribution will be material if it is shown on the evidence not to be negligible (Western Australia v. Watson [1990] WAR 248) 10 • Establishing a mere possibility that a matter has contributed, is not a material contribution to the harm (Seltsam Pty Ltd v. McGuinness (2000) 49 NSWLR 262 at 280 [118], [119] and [153]; see also Forbes v. Selleys Pty Ltd [2004] NSWCA 149 where the Court was not persuaded that the possibility contended for had been established; Kay v. Aryshire & Aaron Health Board [1987] 2 All ER 417; the presence of a satchel in a school corridor having resulted from lack of supervision was only a mere possibility and not established as a probability in Gaitani v. Trustees of the Christian Brothers (1988) Aust Torts Reports, 80-156 ) 11 • An increased risk of injury is not to be equated with a material contribution to satisfy causation (Bendix Mintex Pty Ltd v. Barnes (1997) 42 NSWLR 307 at 312, 316 and 337; State of New South Wales v. Burton [2006] NSWCA 12 at [14] and [91]). Further, it is not enough merely to establish that a particular matter cannot be excluded as a cause; Bendix Mintex Pty Ltd v. Barnes ((1997) 42 NSWLR 307 at 339). Nor does material reduction of risk equate with causation (Bendix; Gold Ribbon (Accountants) Pty Ltd (In Liq) v. Sheers [2006] QCA 335 at [286] per Keane JA) 12 • The evidence must establish a legal inference, and not mere conjecture, that the act or omission complained of contributed to the result. Conjecture, however plausible, is of no legal value, it in essence being only a guess (Law v. Visser [1961] Qd R 46 at 69) 13 • In determining whether the legal inference may be drawn, the Court can take into account common experience (Adelaide Stevedoring Co Ltd v. Forst (1940) 64 CLR 538 at 564) and expert evidence (X v. Pal (1991) 23 NSWLR 26). Some areas may not be within the realm of knowledge for common experience and common sense and fall to be determined upon an analysis of expert evidence (X v. Pal (infra) at 48; see also Da Costa v. Australian Iron & Steel (1978) 28 ALR 257 at 266 per Mason J, with whom Barwick CJ agreed in relation to establishing breach of duty and causation which could only be understood with the assistance of expert evidence in the facts of that case) but that is a question of fact in each case and not a question of law (Gold Coast City Council v. Stocks [2002] QDC 304 at [18]) or necessarily decisive (X v. Pal (infra) at 31) 14 • The legal inference can be drawn, for example, by proof that the incident was of a type that could cause the harm concerned, coupled with a temporal connection (for example in a personal injuries case rendering a previously asymptomatic condition into a symptomatic state; Watts v. Rake (1960) 108 CLR 158; Purkess v. Crittenden (1965) 114 CLR 164; Shorey v. P T Ltd (2003) 77 ALJR 1104). But a mere temporal connection is insufficient (Tubemakers of Australia Ltd v. Fernandez (1976) 50 ALJR 720, 724) 15 • Once that connection has been established (Falacca v. Morrissy [1999] FCA 277), an evidential onus passes to the Defendant to show an alternative cause which would have produced the same result (by external or internal causes) by a certain time (Watts v. Rake (infra); Purkess v. Crittenden (infra); Shorey v. P T Limited (infra)). Otherwise, if the Defendant cannot discharge the evidential onus, such possibilities will only fall for assessment as a contingency in the assessment of damages. If the evidence does not establish this is any greater contingency outside that normally expected, no further reduction of damages will be made (Hopkins v. WorkCover Queensland [2004] QCA 155; see also Seltsam Pty Ltd v. Ghaleb [2005] NSWCA 208) 16 • • Liability for harm may attach to a wrongdoer whose conduct is one of a number of causes of damage (for example the subsequent negligence of a barrister in failing to detect and correct the earlier negligence of a solicitor was not a break in the chain of causation. Both contributed to the Plaintiff’s loss; Bennett v. Minister for Community Welfare (1992) 176 CLR 408; Elbourne v. Gibbs [2006] NSWCA 127 at [74]) Subject to the proportionate liability provisions in the CLA, where applicable, if there are several concurrent tortfeasors to an indivisible loss, liability is unitary, each being severely liable fully to the Plaintiff (see for example Spiers v. Caledonian Collieries (1956) 57 SR(NSW) 483, affirmed (1957) 97 CLR 202). 17 It is for this reason that statutory tortfeasor contribution was introduced, the current incarnation now found in section 6 of the Law Reform Act 1995. In the case of a divisible loss, each wrongdoer is only liable for the divisible component of that loss (Seltsam Pty Ltd v. Ghaleb [2005] NSWCA 208). Several contributions to a loss (divisible or indivisible) are to be distinguished from the causal effect of successive losses or injuries on earlier losses or injuries (as to which see State Government Assurance Commission v. Oakley (1990) Aust Torts Reports, 81-003 at 67,577; Lee v. Quality Bakers Australia Limited [2000] QCA 285; Nilon v. Bizzina [1998] 2 Qd R 420; Faulkner v. Keffalinos (1970) 45 ALJR 1885) 18 Scope of liability • This aspect of the enquiry looks beyond material contribution of cause and subsequent effect. It seeks to normalise, by the application of “common sense”, what might fairly and sensibly be seen, in the eyes of the law, as the cause. “Considerations of policy are relevant and value judgments are required in order to determine matters of causation for the purposes of attributing liability in negligence” (AMP General Insurance Ltd v. RTA (NSW) [2001] NSWCA 186 at [27]). Many adjectives have been used, such as “operative cause” or “substantial” “material” or “real” cause 19 A simple example of the normative enquiry resulting in a failure to establish causation is where an experienced mine deputy had apparently lit a naked flame while undertaking a pre-shift inspection of a coal mine. The mine was not adequately ventilated but the resulting fatal explosion was held to be caused by his actions rather than the lack of ventilation (Sherman v. Nymboida Collieries Pty Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 580) 20 • • Likewise where a deceased injured in an accident, committed suicide following rigorous cross-examination in an application to extend the limitation period, consequent upon which he de-compensated afresh, the suicide was seen as the cause of the loss and not the original accident (AMP General Insurance Limited v. RTA [2001] NSWCA 186; cf Lisle v. Brice (infra)) In Postnet Pty Ltd v. Wood ([2002] ACTCA 5), the Plaintiff entrant in a nightclub was injured after exiting through a window to an awning and then to a nearby building from which he fell. The cause was his deliberate conduct rather than the failure to prevent access to the awning by the occupier 21 • Normative evaluation or value judgments can also extend liability. In Keeys v. State of Queensland ([1998] 2 Qd R 36 at 40-41), McPherson J averted to policy expressly as a reason to extend liability - “[liability] ought not be left to rest on too exact or precise an analysis of what the Plaintiff might or might not have done, had he been given an opportunity, which everyone accepts he ought to have had, to take precautions for his own safety” 22 • Other examples of a normative evaluation supporting liability are where the conduct of the Plaintiff was reasonable, leading to the loss or further loss, such as the voluntary decision to retire from an appointment with secured tenure because of injury (Medlin v. State Government Insurance Commission (1995) 182 CLR 1), the decision to seek out reasonable medical advice which negligently increases the harm (Mahony v. J Kruschich (Demolitions) Pty Ltd (1985) 156 CLR 522) and the decision of a police officer to continue in a high speed chase (Hirst v. Nominal Defendant [2005] 2 Qd R 133). The Plaintiff’s family and cultural background are relevant when considering this normative enquiry (Kavanagh v. 23 Akhtar (1998) 45 NSWLR 558 at 601) • The normative enquiry is particularly important where causation has been considered in a statutory context, such as the Trade Practices Act 1974 or its equivalents. In that respect, what causal connection, if any, is needed and the scope of the intended liability are divined from the true construction of the legislation and its objects (Henville v. Walker (2001) 206 CLR 459; Travel Compensation Fund v. Tambree (2005) 224 CLR 627) 24 The role of subsection 11(1) • The function of subsection 11(1) appears to be to compel a factual appraisal and a direct requirement to address the “normative” question in each case rather than the normative enquiry remaining buried within a reference to a compound “common sense” appraisal. For example, see the approach of the New South Wales Court of Appeal to section 5D of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW), the analogue of section 11, in Graham v. Hall ([2006] NSWCA 208 per Ipp JA) 25 Subsection 11(2) “Exceptional Cases” • This section appears to have been particularly influenced by the writings of Professor Jane Stapleton:- for example “Lords a’leaping evidentiary gaps” (2002) 10 TLJ 276; expressly acknowledged by Ipp JA referring to “Cause-inFact and the Scope of Liability for Consequences” (2003) 119 LQR 388 in Ruddock v. Taylor (infra) at paragraphs [85]-[89] • Professor Stapleton reviewed the role of “material contribution” as espoused in McGhee v. National Coal Board [1973] 1 WLR 1 and Fairchild v. Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd [2003] 1 AC 32. 26 • McGhee/Fairchild, Professor Stapleton argues, directly addressed an evidentiary gap and established a rule of law that, in exceptional cases, a Court is allowed to substitute orthodox proof of cause-in-fact. Professor Stapleton opines that this is a preferable formulation because it is more transparent than suggesting it is part of a process of robust inferences (see Stapleton “Lords a’leaping evidentiary gaps” at 291) • In McGhee, the state of medical knowledge did not permit a finding that the brick dust had caused the Plaintiff’s development of dermatitis. In Fairchild, the mesothelioma may have been caused by exposure to asbestos by a number of employers and the Plaintiff could not isolate which. In both cases the injury was indivisible. Despite this imprecision, the Plaintiff succeeded in both cases 27 against the employer • Professor Stapleton argues that this is jumping the evidentiary gap in the exceptional case of the limits of the best evidence available being reached - in both of those cases, medical evidence – when the contribution of the possibility was established • Whilst McGhee has been approved in Australia by the High Court (see for example Naxakis v. Western General Hospital (1999) 197 CLR 269 at [31], [76] and [127]), Australian Courts have preferred to approach the issue by “inferential reasoning”, elevating a possibility to a probability. 28 For example, in McGhee, the employer’s omission was the only possible cause of the dermatitis, there being no other possibility of equal value. The employer’s breach of duty in that context was highly significant. By comparison, in Wilshire v. Essex Area Health Authority [1988] AC 1074, the Hospital’s omission was only one of a number of possible causes and the Plaintiff had not shown what part, if any, that omission had played 29 • Where direct proof is not available, it is enough if the circumstances give rise to a reasonable and definite inference between competing possibilities. They must do more than give rise to conflicting inferences of equal degrees of probability so that the choice between them is mere conjecture (TNT Management Pty Ltd v. Brooks (1979) 23 ALR 345 at 349-50). As noted above, conjecture is a guess and of no legal value. • A possibility may be elevated to a probability if it can be shown to be of greater value because of some feature, special to the circumstances, or a fact which makes that particular possibility more likely than not, using common experience and expert evidence (Dahl v. Grice [1981] VR 513, 522). Such a state of evidence establishes a basis for a legal inference and is not merely conjecture as the possibilities are not of equal value 30 • If there was only one possibility, established as a fact as a contributory possibility (and not merely a possible contribution as discussed above), a temporal sequence of events and surrounding circumstances suggesting causation, in the absence of an alternative cause being established or even suggested, provides special reason to elevate that possibility to a probability (for example, the simple case and explanation in Barker v. SGIO (Qld) ((1988) 7 MVR 270 at 276 per Williams J, applying West v. GIO (NSW) (1981) 148 CLR 62) • This process of inferential reasoning is well established in Australian law (Girlock Sales (Pty Ltd) v. Hurrell (1982) 149 CLR 155; see also Miller v. Livingstone Shire Council [2002] QSC 180 at [18]; [2003] QCA 29 at [4]). 31 The role of subsection 11(2) • The reference to “whether or not and why responsibility should be imposed” is a reference to the “exceptional case”, such as Fairchild, where the limits of the best evidence explaining causation have been reached. The Plaintiff could not establish which employer was responsible – so they all were • There was no doubt about the breach of each employer but the causal link between a breach by each employer and the condition suffered could not be shown as the Plaintiff could not distinguish between each of the employers. Each breach was a possible material contributor, not just possibly a material contributor 32 • Most cases in Australia will continue to be able to be resolved by orthodox inferential reasoning but subsection 11(2) expressly authorises the jumping of an evidentiary gap where the possibilities are of equal value, as occurred in Fairchild • This section has great potential where a Plaintiff can point to a just result if the best possible evidence has been put before the Court, be that medical, financial, engineering or otherwise. Its precise limits are yet to be discerned 33 The role of subsection 11(3) • Subsection 11(3)(a) adopts the Australian legal position (see for example Chappel v. Hart (1998) 195 CLR 232 at 247, 272-3; Hallmark-Mitex Pty Ltd v. Rybarczk, unreported, QLDCA, 4 September 1998; Hill-Douglas v. Beverley [1998] QCA 435). It is the subjective response of that particular Plaintiff, objectively ascertained, which is relevant 34 • It is the objective ascertainment of that subjective response which is the area of contest. The Courts had long accepted that, the test being subjective, the Plaintiff’s ex post facto statement of what he or she would have done was receivable for objective appraisal but, in many circumstances, would be given little or no weight (Rosenberg v. Percival (2001) 205 CLR 434 at [163], [87][89], [221]; see also Vairy v. Wyong Shire Council (2005) 223 CLR 422 at [226]; Chappel v. Hart (infra)) 35 • The object of subsection 11(3)(b) is, self-evidently, to make the ex post facto hypothecation of the Plaintiff inadmissible, and not just a matter of weight. The subjective response of the Plaintiff may still be proved by propensity evidence, (inadmissible on breach but admissible on causation; Hirbar v. Wells (1995) 64 SASR 129 at 140), commercial intent (Hanflex Pty Ltd v. N S Hope & Associates [1990] 2 Qd R 218), contemporaneous evidence of likely response (see for example Commissioner of Main Road v. Jones (2005) ALJR 1104 at [10]; Enwright v. Coolum Resort Pty Ltd [2002] QSC 394) and even personality traits such as being cautious or, alternatively, being reckless and anti-social (Scarf v. Queensland [1998] QSC 233). 36 • Subsection 11(3)(b) may be seen to be a radical change but, in view of the Court’s reluctance to act on such evidence, its impact may not be as a great as first thought. Note that an admission by the Plaintiff that the act or omission would not have made a difference to the course of conduct adopted, if against interest, is admissible 37 The role of subsection 11(4) • The primary object of subsection 11(4) appears to give express statutory imprimatur to the normative considerations outlined above to either restrict liability or, as Keeys shows, to impose it. This supports the object in subsection 11(1)(b) to expressly require the normative considerations to be addressed 38 Section 12 • Section 12 emphasises two main points:• The Plaintiff always bears the onus of any fact relevant to the issue of causation; • That onus is always on the balance of probabilities 39 The Betts principle • In Betts v. Whittingslowe (1945) 71 CLR 637 at 648-649, Dixon J observed:“The breach of duty, coupled with an accident of the kind that might thereby be caused, is enough to justify an inference, in the absence of any sufficient reason to the contrary, that, in fact, the incident did not occur owing to the act or omission … In the circumstances of this case, that proposition is enough. For, in my opinion, the facts warrant no other inference inconsistent with liability on the part of the Defendant” (underlining added) 40 • Concern has been expressed that this statement has been converted to a statement reversing the onus of proof. The Ipp report viewed some comments in the High Court as tending in this direction (specifically the reasoning of Gaudron J in Bennett v. Minister for Community Welfare (1992) 176 CLR 408 at 420-22; see also McHugh J in Chappel v. Hart (1998) 195 CLR 232 at [34]; Gaudron J in Naxakis v. Western General Hospital (1999) 197 CLR 269 at [31]). For example, in Naxakis, Gaudron J stated:41 “In that situation the trier of fact – in this case, a jury – is entitled to conclude that the act or omission caused the injury in question unless the Defendant establishes that the conduct had no effect at all or that the risk would eventuate and result in the damage in question in any event”. The Ipp report recommended a statutory enshrinement that Plaintiffs always bear the onus of proof of causation on the balance of probabilities:- at [7.36] 42 • This view of the statements in the High Court considering the Betts principle has been rejected in Queensland (Batiste v. Queensland [2002] 2 Qd R 119) in New South Wales (Seltsam Pty Ltd v. McGuinness (2000) 49 NSWLR 262; T C v. State of New South Wales [2001] NSWCA 380; see the review of the authorities by Ipp JA in Flounders v. Millar [2007] NSWCA 238 at [22]-[39]) and in Victoria (Shire of Wakool v. Walters [2005] VSCA 216 at [48]) but accepted in Western Australia (Amaca Pty Ltd v. Hannell [2007] WASCA 158 at [395] 43 • It is for this reason that the legislature has intervened. It does not change the law in Queensland • The Queensland (and, with respect, the better,) view is that the Betts principle refers to a shifting evidential onus. If a breach is established consisting of an omission to take a proper precaution, in determining whether the Plaintiff would have acted in such a way as to avoid the risk (the negative aspect of causation), it is open to the Court to infer that the Plaintiff would have so acted in the absence of any sufficient reason to the contrary 44 • All members of the Court of Appeal in Batiste approached the question in this way. The majority viewed Betts as authorising the drawing of an inference in the context of determining, as a question of fact, whether there are any other competing inferences of equal or greater probability. Their Honours were of the view that the real question was whether the trial Judge had averted to competing causes and formed the view that the conclusion reached by the trial Judge was open. Muir J, who dissented, on the other hand, was of the view that “the trial Judge had erred by treating the Betts principle as one which ignored the need to look for the existence of any reason which would negate the inference which [the trial Judge] was entitled, but not obliged, to draw” (at paragraph [39]) 45 • This emphasises the need in such a case for evidence negating the inference, or competing hypotheses, to be placed before the Court. That evidence may take many forms in the circumstances of the case, similar to that involved in evaluating competing established possibilities – for example, commercial intent, disposition, previous conduct, and contemporaneous action. The problem is particularly difficult where causation turns on what a Third Party would, or would not have, done. In such circumstances, a Court may be slow to draw such an inference but it may properly be drawn where the behaviour of the Third Party is objectively likely, for example, where the Third Party’s self interest points at a particular direction (per Keane JA in Gold Ribbon (Accountants) Pty Ltd (In Liq) v. Sheers [2006] QCA 335 at [281] and [284]) 46 Loss of a chance • Concern also exists that there has been a weakening of the civil onus in cases of loss of a chance of a benefit or avoiding a detriment • The distinction must be maintained between identifying a species of “damage”, being the loss of the chance, which is recoverable if caused by a breach, on the probabilities, and the assessment of that lost chance as “damages” 47 • It is submitted the authorities establish the following:•In negligence, the tort is not complete until “damage” has been suffered (Rankin v. Garton Sons and Co Ltd [1979] 2 All ER 1185 at 1189). “Damage” only accrues when it is beyond what can be regarded as negligible (Martindale v. Burrows [1997] 1 Qd R 243 at 246 per Derrington J; Orica Ltd v. CGU Insurance Ltd (2003) 59 NSWLR 14 at page 22 “sufficiently material”). In contract, a breach if actionable without loss (See the authorities collected by Lindgren J in Cell Tech Communications Pty Ltd v. Nokia Mobile Phones (UK) Ltd (1996) 136 ALR 733 at 750) but recovery of substantive, and not nominal damages, requires proof of a loss of substance 48 •That a chance of avoiding a detriment or gaining an advantage has been lost must be established by the Plaintiff on the probabilities (Green v. Chenoweth [1998] 2 Qd R 572; see also Hill-Douglas v. Beverley (unreported, QLDCA, 18 December 1998); see also Gold Ribbon (infra) at [284]). This includes the chance of a better outcome (Rufo v. Hosking (2004) 61 NSWLR 678, especially at paragraph [40]; Gavalis v. Singh [2001] 3 VR 404) •The Plaintiff must establish, on the probabilities, the chance was lost as a result of the alleged breach (Rufo at paragraphs [40] and [41]; Green v. Chenoweth (infra); Hill-Douglas v. Beverley (infra)) 49 If such a chance is established, on the probabilities, then it is damage sufficient for a claim in contract, tort or (depending on the statute) on a statutory basis, such as the TPA (Sellars v. Adelaide Petroleum NL (1994) 179 CLR 332, applying Malec v. JC Hutton Pty Ltd (1990) 169 CLR 638 to the assessment of damages under the TPA), if the lost chance is a chance “of substance”, or, of “some value not being negligible”, rather than “speculative” (Bradley v. Stanek (unreported, QLDCA, 18 December 1998) at [10][11] per McPherson JA, with whom McKenzie J agreed; see also Rufo (infra) at [3] and [4]; CES v. Super Clinics (1995) 38 NSWLR 47 at page 57 per Kirby P “a loss of that opportunity itself being of value to the Appellants because of the possibility of her availing herself of the opportunity … the Appellants would have to establish that loss or damage had been sustained by deprivation of the opportunity. However that would be done by simply demonstrating that the opportunity which was lost by the Respondent’s negligence was of some value, but not negligible value, to the Appellants” (underlining added) 50 •The evaluation or assessment of the lost chance for damages (not damage) is “ascertained by reference to the degree of probabilities or possibilities” (Sellars (infra) at 355; Bradley v. Stanek at [11]) • The loss of chance approach might erroneously conflate establishing the existence of the chance, on the probabilities, as “damage” with the assessment of the chance as “damages”, especially where the chance claimed is more than 50% (cf Naxakis (infra) at [312]-[313] per Callinan J; New South Wales v. Burton [2006] NSWCA 12 at [25] and [27], [80]; Halverson v. Dobler [2006] NSWSC 1307 at [248]). For example, in Halverson, it was said: “… insofar as ‘loss of a chance’ presently has a place in personal injury cases on the current state of the law in New South Wales, it is in cases where the Plaintiff cannot prove causation on the balance of probabilities, and, accordingly, the lost chance is less than 50%” (underlining added) 51 • This does not authorise the assessment of damages if the Plaintiff cannot prove causation on the balance of probabilities. Rather, the distinction is drawn between causation of the whole loss on the one hand and a case framed by establishing, on the probabilities, a lost chance of less than 50%, on the other. According to the civil onus, if it established that the chance is more than 50%, causation is proved in relation to the whole • The role of section 12 in this respect is to mandate that the civil onus, the balance of probabilities, has not been diluted. 52