C4D Literature Review, UNICEF, 2014

advertisement

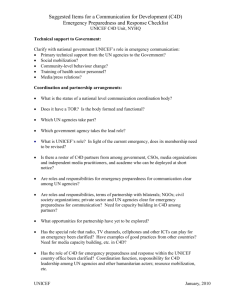

Communication for Development and Emergencies: A Literature Review of Existing Approaches and Tools A summary report reviewing existing evidence, approaches and practical tools focused on the role and use of communication during emergencies Andrew Skuse, PhD Independent Consultant DRAFT January 18, 2014 A Report Commissioned by UNICEF/NYHQ Programme Division/Communication for Development Section Acronyms AAP BCC C4D C4HA CDAC CDC CFSC DFID DRR HA ICRC ICT4D IEC IFRC IPC KAP QA SFCG UNICEF UNDP UNESCO UNFPA UNHCR UNOCHA USAID Accountability for Affected Communities Behaviour Change Communication Communication for Development Communication for Humanitarian Assistance Communicating with Disaster Affected Communities Network Centres for Disease Control Communication for Social Change Consortium UK Department for International Development Disaster Risk Reduction Humanitarian Assistance International Committee of the Red Cross Information and Communication Technologies for Development Information, Education and International Federation of the Red Cross Interpersonal Communication Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice Quality Assurance Search for Common Ground United Nations Children’s Education Fund United Nations Development Programme United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization United Nations Population Fund United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance United States Aid 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 1. Introduction 8 2. Methodology 8 3. Summary of Evidence 10 4. Conclusion 20 Annex 1 Summary of Included Literature 22 3 Executive Summary Background This literature review has focused on the range of practical resources and tools available for use in emergency/disaster settings. The rationale for undertaking the review is to assess how previous resources have addressed the topic and what we might learn from them in attempting to develop a user-friendly toolkit that is simple, but still adheres to known communication principles, latest evidence and approaches that help to assure quality and effectiveness. Such approaches and tools are most commonly associated with C4D/BCC-type communication approaches, as well as with social change and participatory communication frameworks. These approaches seek to engage with communities, identify information needs, communication uses and preference, understand behaviour and constraints to behaviour change, while also defining clear objectives, engaging in pretesting to ensure relevant and undertaking evaluation for the purpose of learning. The methodological approach taken was pragmatic and focused mainly on resources developed by organisations that fall into the ‘practitioner’ category. Academic literature was generally not assessed, though a relevant systematic review summarising a significant amount of relevant literature has been included to add a counterbalance to the practitioner literature. A process of manual searching against the selected search terms was used to find a representative sample of material from a wide number of organisations involved in the delivery of humanitarian assistance and development. Both resources that focused on emergencies and non-emergency contexts were included for review to enable learning from both forms of literature. These resources were added to through snowballing, and through knowledge of previous source derived from the author’s similar work for a number of organisations. Findings The review found the following findings: - The literature reviewed falls that examines formal emergency communication treats communication as a core asset with emergency responses and is generally not designed and evaluated with the same rigour as C4D-focused communication interventions; The literature that addresses the C4D-focused approaches in emergencies engages a fairly conventional approach to communication design and implementation, drawing heavily on formative research, the use of quality assurance practices and upon ongoing and summative evaluation; - Much of the formal emergency communication literature derives from developed world contexts and is generally not supported by a clear theoretical or methodological focus. The absence of field methods in many resources suggests that their primary concern is with information giving, warning messages and evacuative action, rather than any sense of behaviour and social change. There is a clear opportunity to enhance emergency communication through the application of some basic methodological tools; - Most of the emergency and non-emergency literature promotes some form of process/cycle to follow during a crisis and most promote a range of principles and/or steps that can be adhered to in a crisis situation. The non-emergency or BCC-focused material is stronger on steps, principles and quality assurance tools that can help ensure effectiveness; - Many resources promote generic message sets and there is value in ensuring that communication practitioners have generic sets of messages that can be communicated in an initial crisis period. A balance needs to be struck between promoting a prescriptive response through generic messaging and the development of context specific research informed messaging. Further, there is a critical need to build dialogue before, during and 4 after emergencies and while message giving can positively affect the public information environment it is not effective in creating dialogue; - Much of the literature, both emergency and C4D-focused recognises the need to create dialogue. This places a critical emphasis on both the communication channels engaged, i.e. face-to-face communication and community mobilisation is effective at creating dialogue, while certain genres of communication, such as drama have been shown to stir public debate very effectively. Building positive dialogue is one of the key goal of emergency communication; - New Technology is playing an increasingly significant role in humanitarian emergencies, though much has been made from a small number of mainly crowdsourcing and crisis mapping examples. Further, there is still much to learn about how the humanitarian community and largely volunteer crisis mapping communities can work together. Numerous developing world emergencies feature communication contexts characterised by unequal access to new ICTs and dominance of traditional media access and interpersonal communication. The UNICEF toolkit needs to balance promoting and integrating using new ICTs into emergency responses without them taking precedence; - Defining the focus of the emergency timeframe that the toolkit will focus on is critical to containing its scope. Numerous existing resources address the preparatory and recovery phases of disasters in detail. There is a lack of C4D-type resources that focus on the acute period of a disaster and it is here that the most value can be added through the development of a toolkit; - Many of the better, more practical resources, contain a specific focus on quality assurance, and especially pretesting to ensure relevance and suitability of communication outputs. They promote simple tools and checklists that can help practitioners to test their assumptions; - The accountability to affected populations (AAP) and resilience agendas are weakly reflected in the bulk of the literature reviewed. The AAP agenda challenges the humanitarian sector to communicate more effectively with communities, especially around the broad role of humanitarian assistance, and service provision in order to create demand and foster accountability, rather than around specific thematic issues, such as conflict reduction or Cholera. This represents a challenge that must be addressed in the toolkit development process; - With one or two exceptions the resources reviewed are too long, too technical and most likely difficult to implement in emergency situations. Their length and complexity is driven by the need for methodological rigour and a key challenge associated with the development of the toolkit is how the essence of this rigour can be maintained, while much of the detail and method associated with these approaches is removed. Recommendations The following recommendations are drawn from the literature review and have implications for the development of the UNICEF toolkit. Several recommendations are of broader relevance to UNICEF’s C4D practice. Toolkit recommendations: - There is clear value in UNICEF maintaining a focus on C4D/BCC principles, albeit in extremely light form. It can add value, but should not place implementation staff at risk. For example, the collection of formative data during conflict may be highly dangerous, but such data is deemed critical to designing effective C4D initiatives. A short section on recognising and negotiating risk will help practitioners make sensible choices, while pointing them to 5 alternative data sources or methods of field data collection/testing (some driven by emerging ICTs). Existing resources cover aspects of risk quite poorly; - There is no value in UNICEF adopting a strictly emergency communication approach because comprehensive emergency resources already exist and UNICEF’s comparative advantage lies in approaches that target behaviour change and social action (as promoted through C4D). Use of the ‘emergency’ tag in previous UNICEF publications has cause confusion for users from other organisations. Given this, there is logic in losing the emergency tag altogether in favour of the broader term humanitarian assistance. Focusing on what can be termed Communication for Humanitarian Assistance or C4HA would enable the resource to speak directly to emergencies while also addressing the accountability agenda by helping communicate the role/function of HA. Finally, the UNICEF approach has been to promote substantial and rigorous C4D/BCC guidance in for use in emergencies, rather than promoting a radically slimmed version of the C4D/BCC approach that is simple and accessible. Simplicity (with rigour) and conciseness will result in the biggest uptake for the resource. - The toolkit should cover in modest detail the transition to longer-term support and recovery initiatives and the shift from preparation phases to emergency communication. This will help to limit the scope of the resource, but also help users to identify when things have changed and point them to resources that can help. There is clear merit in focusing on a discrete timeframe (see section below) and promoting a more rigorous C4D/C4HA approach. There are enough high quality resources that address recovery, but few that offer a rapid C4D/C4HA-focused approach for acute emergencies; - Prioritise rapid formative data collection for strategy design and development over impact data. Ensuring the relevance of communication design, appropriateness of messages, various channels/mechanisms employed and quality of outputs is critical to effectiveness. Investment in formative processes is critical, understanding impacts can be more problematic. Formal emergency communication places value in getting information out and dialogue going, but places little emphasis on understanding impacts (often because many emergencies are short-lived, especially in the developed world from where the bulk of the literature emanates). In complex media environments it is also increasingly difficult to identify causality (i.e. directly link behaviour change to a specific communication initiative). In the developing world the same is largely true. While it is important to understand impacts, if context allows, more emphasis should be placed on formative evaluation. If that is rigorous, effectiveness and impact is likely to follow. Consequently, objective setting, indicator identification and summative evaluation processes should be modest and ‘doable’; - At minimum the toolkit should include focus groups or key informant interviews to compliment quantitative KAP surveying to ensure QA feedback and subtle behavioural data is secured. Such data can be secured with minimum numbers of focus groups; as such data is inherently subjective, but nonetheless valuable in testing assumptions; - Engagement with more extensive qualitative methods should be avoided for practical reasons of risk, lack of synthesis and analysis capacity in many organisations and its timeconsuming nature; - Resources that have clearly definable steps that are geared towards generating a simple C4HA communication strategy will have more applicability in context; - Initial work on toolkit development should prioritize collating existing approaches, initiatives, mechanisms, tools and steps (identified in this review) to form a long list that can be simplified and reduced; - Building a limited bank of generic messages is essential to the rapid deployment and use ability of the toolkit; - Messages should cut across HA delivery, BCC/C4D and advocacy; 6 - Building in a process for considering message localization will help stop the toolkit becoming a prescriptive resource that is used uncritically; - Integrate role of new ICTs throughout the toolkit, especially in the areas of data collection, KAP and emergency SMS messaging (and other ICT channels). Do not build a separate section relating to new ICTs; - Chose a realistic emergency timeframe to ensure that fewer rather than more steps are included in the toolkit. The CDC 4-step cycle of 1-3 days after a disaster, 3-7 days after, 14 weeks after and the one-month plus period is more practical and is therefore preferable. It is clear that such a timeframe does not cover all types of emergencies and some are much longer, so succinct material on the transition from the one-month plus point to longer term initiatives is important; - The toolkit should only cover acute/rapid onset emergencies and not try to cover more mainstream development processes. This will help focus the resource, help to partners, such as Red Cross and wide UN bodies and help keep the resource light; - Include simple QA tools throughout to aid message development and pretesting in particular. These can link to and support communication effectiveness principles to ensure that as users work through the toolkit they absorb some of the essence of what a C4D/BCC approach is concerned with; - Include resilience as a brief framing theory that helps tie the wider humanitarian communication objectives together. Here resilience could be linked to the notion of communication as a protective asset and to the participation of AAP for dialogue; - Develop a paper and web/app version of the toolkit, both of which are geared towards the production of a defined emergency communication strategy/plan that can be adapted as needs change. This will ensure widest coverage of potential audiences; - Each section or step should have a consistent format, with: (i) communication approaches and principles; (ii) question sets that with help users generate answers that can be used to flesh out their strategies; (iii) simple methodological tools that enable these questions to be asked; (iv) simple quality assurance tools that help user ensure relevance. In addition, simple objective setting and M&E can be promoted, but with a preference for formative and pretesting work, rather than impact evaluation; - Limit the scale (i.e. no more than 30 pages for the ‘super-light’ tool and no more than 50 pages for the longer version) of the resource to ensure that it is light and focuses only on the essential methods, tools, principles and quality assurance mechanisms; - The toolkit development process must ensure that the various factors identified in the review of academic literature are supported in the outputs and that identifying supporting frameworks and clear outcomes resulting from communication is important. UNICEF recommendations: - UNICEF may want to further explore the concept of resilience in the context of C4D/BCC approaches to ensure that a rigorous data-driven link is established between communication and increased resilience, as it is a multifaceted asset that is potentially riddled with socio-cultural constraints; - UNICEF might want to consider undertaking a separate assessment of how its wider body of C4D resources is used and adapted at the local level as a way of understanding how to communicate technical advice going forward. 7 1. Introduction 1.1 This literature examines the role of emergency communication in the context of humanitarian and complex emergencies. In particular, it focuses on the range of practical guidance and, tools that have been developed to help humanitarian and development organisations build effective communication initiatives in contexts characterised by risk. Unlike conventional C4D, emergency C4D requires a rapid response and approaches that are highly efficient, yet robust enough to offer relevant and rigorously designed outputs. This review focuses on literature for both emergency and non-emergency settings that offer insights into emergency communication practice, as well as those that identify practical tools, strategies and design frameworks for use by field practitioners. 1.2 The literature selected for review is that deemed to be most relevant, while adhering to wellestablished principles of C4D best practice. These include engaging in formative media uses and behavioural and social research, disaggregating audiences, developed group-specific messages, engaging in quality assurance through pretesting, promoting consistent messages and issues over multiple communication channels and engaging in rigorous monitoring and evaluation for lesson learning and program adaption. In addition, a preliminary workshop meeting held on 16-17th December at UNICEF Headquarters has provided additional focus for this review. It was concluded that the toolkit could: - Give guidance for risk informed sectoral interventions, including the transition from communication for humanitarian assistance to communication for development; Be light; Provide minimum standards; Provide information for each phase of the humanitarian assistance and/or development programme cycle; It must be clear who is the end user; Provide options for different case scenarios; Include quick assessment for communication needs; Strengthen the monitoring and evaluation component. 1.3 This initial list of issues will be considered in this review, along with additional issues emerging from the literature examined. In addition, the humanitarian community is committed to improving accountability for affected communities (AAP), which entails an increased focus on communicating the program activities associated with humanitarian assistance. This communication function is in addition to the sectoral and thematic focus of the resources reviewed here, but is critically important to building dialogue with communities and trust. Finally, a key forward-looking objective of UNICEF is to adopt a resilience approach to their work in which, in conjunction with bilateral, multilateral, government and NGO partners, they seek to enhance the capacity of communities to prepare for and respond to emergencies. From a C4D perspective this involves using targeted communications activities to help reduce risk and vulnerability and through building capacity to enhance disaster preparedness. 2. Methodology 2.1 The methodology employed to identify relevant sources that explicitly focus on emergency communication approaches, design and practical tools resulted in standard academic databases such as Scopus, Academic Search Premier, Ingenta Connect, Google Scholar, not being favoured within the search strategy. Given the specialist nature of C4D and emergency communication the search strategy was tailored to databases relevant to the particular thematic area. The methodology employed in this literature review follows a three-step process that includes: (i) the identification of relevant search terms/keywords; (ii) the identification of relevant sources from practice-focused databases; and (iii) the snowballing of sources through examination of reference lists of found literature. 2.2 An initial list of search terms was developed and expanded, and then used to source literature, though the poor search functionality of non-academic databases significantly limited 8 search efficiency. Search terms included: - Accountability BCC Behaviour Building C4D Campaign Change Children Civic Civil Communication Conflict Democratisation Development Disaster DRR Education Emergency Ethnic - Fragile Gender Governance Health Human Humanitarian ICT4D IEC Information Interpersonal KAP Legislation Media Mitigation Network New Participation Peace Policy - Print Radio Reduction Refugee Recovery Reporting Resilience Rights Risk Social Stabilisation State Strengthening Telecom* Television Video Violence Vulnerability War 2.3 These terms were used to manually search (via trialling combinations of search terms) the websites of the organisations listed below. These organisations are known to have a role in either C4D or in providing support to communities experiencing humanitarian or complex emergencies. A wide number of organisations were chosen to search to ensure a broad crosssection of evidence was returned. Where multiple sources were found only the most relevant material was included for assessment in this review, i.e. that which focuses on emergency communication approaches, design and practical tools. Some material returned does not focus on emergency communication but on broader C4D issues, though these have been included due to their relevance to the development of concise tools. - BBC Media Action CDAC (Communicating with Disaster Affected Communities) Network Centres for Disease Control (CDC) Communication for Social Change Consortium (CFSC) FHI 360° International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC) Search for Common Ground (SFCG) The Communication Initiative UK Department for International Development (DFID) United Nations Children’s Education Fund (UNICEF) United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance (UNOCHA) USAID World Bank WHO 2.4 Some background documents where provided by UNICEF. In addition, this literature review draws on some previous work undertaken by the author, which also included the systematic collection of literature relating to communication for development in fragile states, during complex emergencies and in support of humanitarian processes. These include: - Skuse, A. et al. 2013. Communication for Development Interventions in Fragile States: 9 A Systematic Review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports JBL000566, 11(3): 1-190. - Skuse, A. et al. 2013. Social Networking, Social Media and Complex Emergencies: an annotated bibliography. Australian Civil-Military Centre, Canberra, pp.1-70. 2.5 Where appropriate, sources identified in these documents have also been included to support this paper. Finally, the initial material identified was subject to the process of snowballing, whereby the reference lists of sourced literature is examined for additional work of relevance to the review. Material not selected for inclusion in this literature is not reported in this review (for the sake of efficiency). Some material was of conceptual relevance, but offered little by way of practical tools and these are included, but not subject to full review. The search strategy and subsequent snowballing process sought material only from the period January 2004 - December 2013. This helped to ensure that literature was current and reflected the most recent developments in the delivery of humanitarian and emergency communication. Some resources had no publication date and were included for the relevance of their content. Only studies published in English were considered for inclusion in this literature review, though it is critical to note the important contributions of authors writing in languages other than English. 3. Summary of Evidence Emergency Communication and BCC: a clash of perspectives? 3.1 The evidence reviewed points to a divergence in approaches and understanding of what constitutes emergency communication. The bulk of emergency communication literature derives from developed world contexts and it constitutes a well-developed approach with clear processes, practices and parameters. The term emergency communication refers to the rapid conveying of emergency information through organisations and channels that have the capacity to immediately shift their focus. Publications from CDC, Australian Government and a wide range of USA Department of Homeland Security (not reviewed) are principally focused on rapid mobilisation of an information response to an emerging crisis, i.e. a terrorist event, flood or bush fire. The provision of accurate and verified information is critical, but within the bulk of evidence that falls formally within the ‘emergency communication’ field there is less concern with formative research, behaviour and social change and impact evaluation over the function of the timely provision of information. 3.2 In developed world settings, where robust services exist to address health and humanitarian needs, the principle focus of emergency communication is on risk avoidance, responding to danger and evacuation. The primary goal of most emergency communication frameworks is to invest in extensive preparation, i.e. ‘know your emergency plan’, and during the crisis event, the goal is to get at risk populations to ‘act now’. This is captured by the CDC (5) in their comprehensive emergency communication manual, where the state: - Be first; Be right; Be credible; Express empathy; Promote action; Show respect. Finally, with their ability to mobilise social media channels quickly developed world emergency communicators are quick to establish a dialogue to at risk populations, which aids both accountability and the provision of information in real time. This can be the case in the developing world, as the example of the Haiti earthquake response has shown, however in contexts with limited Internet and mobile telecommunications access such responses remain some way off. 10 3.4 Within the developing world, where less robust services exist and emergency responses may be less robust communication tends to play a far broader role, from early warning of impending disasters to promoting community responses to the resulting health, social and infrastructural problems that they bring. The bulk of literature that focuses on emergencies in the developing world tend to prioritise well-known C4D/BCC principles and processes such as formative research, audience segmentation, multiple context-specific messages, multi-channel dissemination, ongoing evaluation, pretesting, content revision and so on. The literature is geared towards a few core functions: - - Rapid communication context mapping; Emergency communication in immediate response to a disaster, focus on mobilising media, emergency management plans and communicating warnings and generic messages; Understanding diversity of risks and promoting behaviour change through targeted thematic and sectoral communication interventions, especially in the preparatory and postemergency phases; Promoting the role and function of humanitarian assistance (in accordance with the accountability for affected populations framework). 3.5 The C4D/BCC-type literature examined fell into both the emergency and non-emergency bracket, but differed little in the detail and complexity of approach beyond the need for more urgency in emergency situations. Again the tension between the formal emergency communication literature and C4D/BCC approach resides in a difference of perspectives about the role of information and communication, with the former seeing it as a routine asset that is provided like any other asset, whereas the C4D/BCC approach is one that is driven by evidence and the impetus to prove impacts (i.e. behaviour change). Many of the tools and frameworks examined fail to recognise the difficulties of conducting a C4D/BCC approach within an emergency situation and few makes detailed statements of how and when the approach should be modified to ensure staff remain safe in the face of an emergency. 3.6 The issue of a clash of perspectives was noted in the preliminary group meeting of the 1617th December, which discussed the need to come up with a name that could replace C4D/BCC since it did not resonate well with different agencies. Suggestions included Communication 4 Emergencies (C4E) and Communication for Humanitarian Action (C4HA). It was noted that the name should speak to a wide set of issues, including: - Participation; Two-way communication; Humanitarian Action; Behaviour and social change; Advocacy; Accountability for Affected Populations (AAP); Communication with Communities. The preliminary meeting also noted that a holistic BCC/C4D approach would probably be untenable. Holding on to the basics of the C4D approach is important and a focus on a toolkit that equates to a C4D-light would help to ensure that minimum communication standards are met. Recommendations: - There is clear value in UNICEF maintaining a focus on C4D/BCC principles, albeit in extremely light form. It can add value, but should not place implementation staff at risk. For example, the collection of formative data during conflict may be highly dangerous, but such data is deemed critical to designing effective C4D initiatives. A short section on recognising and negotiating risk will help practitioners make sensible choices, while pointing them to alternative data sources or methods of field data collection/testing (some driven by emerging ICTs). Existing resources cover aspects of risk quite poorly; - There is no value in UNICEF adopting a strictly emergency communication approach because comprehensive emergency resources already exist and UNICEF’s comparative 11 advantage lies in approaches that target behaviour change and social action (as promoted through C4D). Use of the ‘emergency’ tag in previous UNICEF publications has cause confusion for users from other organisations. Given this, there is logic in losing the emergency tag altogether in favour of the broader term humanitarian assistance. Focusing on what can be termed Communication for Humanitarian Assistance or C4HA would enable the resource to speak directly to emergencies while also addressing the accountability agenda by helping communicate the role/function of HA. Finally, the UNICEF approach has been to promote substantial and rigorous C4D/BCC guidance in for use in emergencies, rather than promoting a radically slimmed version of the C4D/BCC approach that is simple and accessible. Simplicity (with rigour) and conciseness will result in the biggest uptake for the resource. - The toolkit should cover in modest detail the transition to longer-term support and recovery initiatives and the shift from preparation phases to emergency communication. This will help to limit the scope of the resource, but also help users to identify when things have changed and point them to resources that can help. There is clear merit in focusing on a discrete timeframe (see section below) and promoting a more rigorous C4D/C4HA approach. There are enough high quality resources that address recovery, but few that offer a rapid C4D/C4HA-focused approach for acute emergencies; - Prioritise rapid formative data collection for strategy design and development over impact data. Ensuring the relevance of communication design, appropriateness of messages, various channels/mechanisms employed and quality of outputs is critical to effectiveness. Investment in formative processes is critical, understanding impacts can be more problematic. Formal emergency communication places value in getting information out and dialogue going, but places little emphasis on understanding impacts (often because many emergencies are short-lived, especially in the developed world from where the bulk of the literature emanates). In complex media environments it is also increasingly difficult to identify causality (i.e. directly link behaviour change to a specific communication initiative). In the developing world the same is largely true. While it is important to understand impacts, if context allows, more emphasis should be placed on formative evaluation. If that is rigorous, effectiveness and impact is likely to follow. Consequently, objective setting, indicator identification and summative evaluation processes should be modest and ‘doable’. Methodological Focus 3.7 Much of the literature on formal emergency communication has no clear theoretical framework or methodologies associated with them; an exception would be the CDC manual (see Ref. 5). Despite caveats concerning dialogue this literature is largely written from the standpoint of governments informing citizens without a significant underpinning formative research or evaluative process. The C4D/BCC is closely linked to behavioural, psychosocial and social frameworks and promote methodological tools that are capable of generating data on knowledge, attitudes, practices and behaviours, as well on media uses, preferences, media sectoral data, capacity needs and policy and legislation. 3.8 Theoretical frameworks tend to dictate the types of methodological tools promoted in the resources reviewed, with social change approaches promoting purely qualitative methods and those promoting BCC suggesting more multi-method approaches based quantitative KAP surveying and qualitative behavioural assessment, often through focus groups and/or in-depth interviewing. In addition focus groups are used extensively to monitor message relevance and the quality/clarity of outputs. Generally, quantitative KAP surveying, while capable of telling you if KAP variables are positively increasing tends not to be capable of supplying the subtle data on behaviours necessary to developing a context-relevant communication strategy or localising generic message sets. Further KAP surveying may not be able to provide a causal link between a communication initiative and shifts in KAP variables, especially in complex media/communication environments. However, in an emergency situation such considerations should not be perceived as important as getting the message out and across. Also, effective 12 coordination can help get a consistent message across platforms/channels/organisations making its impact greater in the process. multiple 3.9 While KAP has its problems, it is easy to conduct and can yield robust data based on small randomised datasets. Qualitative methods on the other hand, while yielding subtle data of great use to developing communication strategies can be difficult to conduct in emergency settings, especially where conflict is present. In non-emergency settings methodological approaches such as ethnography or participatory methods can lead to large quantities of data and a reliance on international technical assistance for analysis/reporting (see Ref. 20). The development of an optimal mix of methods for inclusion in the UNICEF toolkit will require field-testing, but at minimum should include a mix of KAP surveying (quantitative data), focus groups (behavioural data & QA processes) and individual interviewing (behavioural data & advocacy development). Recommendations: - At minimum the toolkit should include focus groups or key informant interviews to compliment quantitative KAP surveying to ensure QA feedback and subtle behavioural data is secured. Such data can be secured with minimum numbers of focus groups; as such data is inherently subjective, but nonetheless valuable in testing assumptions; - Engagement with more extensive qualitative methods should be avoided for practical reasons of risk, lack of synthesis and analysis capacity in many organisations and its timeconsuming nature. Focus on principles/steps 3.10 Many of the toolkits and resources examined in this review contain either: (i) overarching sets of humanitarian communication principles that help define the whole resource: (ii) principles that guide each substantive section, tool or approach; or (iii) both. The preliminary group meeting of the 16-17th December discussed a number of broad principles, including: - Crisis affected people; households and communities are best placed to articulate their humanitarian needs; Strengthening effective communication systems and enabling genuine participation will result in more positive humanitarian outcomes; Messages from humanitarian community should be coordinated, based on available information and build on existing best practice; All needs assessments should have questions related to communicating with communities; Government ownership/involvement is ideal but not a precondition; Strategy for Communication with Communities should evolve over time and remain responsive and relevant; We will make sure that all groups especially the most marginalized/at risk are represented in ‘the community’. These, and other principles identified in the literature review, such as the AAP and CDC principles can combine to make a powerful statement concerning the values that the toolkit seeks to promote. The principles identified should focus explicitly on what is achievable within the timeframes that the toolkit speaks to, i.e. emergencies (see section on timeframes). 3.11 Within many of the toolkits/resources examined sets of C4D/BCC principles accompany each section. Principles identified in the literature include, but are not limited to the following: 13 1. Be Process Orientated 12. Evaluate and Learn 2. Conduct Formative Research and Pretesting 11. Advocate to Change Policy and Legislation 3. Diverse Audiences Exist 12 Principles for Effective Communication in Emergencies 10. Build Dialogue for Accountability 9. Work with and through Communities 5. Target Specific Messages at Specific Groups (CwC) 8. Link to and Communicate Service Delivery (AAC) 4. Use Multiple Communication Channels 7. Promote Consistency and Accuracy 6. Target Action Not all of the above principles necessarily equate to strategy development steps, but most of the literature reviewed contains these or very similar principles/steps. UNICEF’s Cholera Toolkit (see Ref. 11) contains a number of useful appendices (7A – 7H) that cover a similar range of principles/steps, including the ‘basics of communication approaches’, which provides a succinct communication plan template, a preparatory work plan template, communication methods/channels, key messages/actions/behaviours, community beliefs and perceptions, working with communities, and an IEC work plan template. This material is detailed and could be slimmed down and Recommendations: - Resources that have clearly definable steps that are geared towards generating a specific component of a communication strategy will have more applicability in context; - Initial work on toolkit development should prioritize collating existing material/tools/steps (identified in this review) to form a long list that can be simplified and reduced. Messaging: striking a balance between emergency messaging and behavior change messages 3.12 The literature on emergency communication is dominated by information giving and communicating official verified updates and public warnings. The Australian Government (see Ref. 9) focus on messaging promotes consistency and accuracy, but also notes that emergency communication is a dialogue (which is increasingly pushed through social media, but also interpersonal, peer and social mobilization mechanisms). It suggests: - Don’t make assumptions; It is a dialogue with the community, not a command situation; Responding to warnings is a process, not a single step; Recipients of the message will have a need to confirm the message before they are likely to take action; 14 - Consistency is critical; Accuracy is important; Be as specific as possible; Don’t leave gaps; If people are likely to be familiar with previous similar emergencies, use these to ‘benchmark’ the impending situation; Recipients may be getting the messages under conditions of stress; Where the target audience includes people who do not speak English as a first language there may be a need to simplify word choices. 3.13 While this type of messaging is important, UNICEF and its partners are dealing with a wider set of issues that is highlighted by Pacific Humanitarian Protection Cluster (see Ref. 8) who provide a list of generic messages covering: - General Protection in Disasters; � Psychosocial Impacts; Protection of Older People/People who are Sick or Injured/People with Disabilities; � Protection against violence and abuse; � Child Protection; � Environmental Hazards; � Staying in Evacuation Centres;� Children & Youth in contact or conflict with the law. 3.14 Existing UNICEF publications and internal resources provide generic sets of messages that are important for communication practitioners to access during acute emergencies. These explore issues central to UNICEF’s mandate such as health, nutrition, water and sanitation. Many messages concerning issues such as health may not change from context to context, but it is also important that messages are contextualized wherever the context allows and link to real service delivery/HA. Increasingly, the focus of accountability frameworks has been on ensuring that the scope of HA is communicated in its own right. This means that the promotion of HA increasingly must sit alongside, BCC or action focused communications, as well as advocacy messages, if communities are to be fully included in humanitarian processes. 3.15 While there are risks in promoting generic message sets (i.e. may prevent localization), they may be essential in the initial weeks of an emergency. Notably, the Infoasaid library of generic messages is no longer available. Finally, a web/app version toolkit could allow a user to select specific message sets based on the challenges faced, with the strategy development process required a minimum degree of local adaptation. Therefore it is critical that the toolkit provides core message sets, but also promotes simple C4D/BCC tools that enable users to define, develop and test their own messages. Recommendations: - Building a limited bank of generic messages is essential to the rapid deployment and use ability of the toolkit; - Messages should cut across HA delivery, BCC and advocacy; - Building in a process for considering message localization will help stop the toolkit becoming a prescriptive resource that is used uncritically. Emergency Communication: the role of new technology? 3.16 There is a growing body of work on the role of social and mobile media in the context of emergencies. The Haiti earthquake, Japanese Tsunami and Arab Spring crises have highlighted the emerging role of such technologies in linking citizens and in promoting and sharing citizen media, commentary and community action in response to conflict and disasters. Much social media communication is beyond the influence of humanitarian assistance organizations and users tend to trust peers, rather than organizations. Further, many 15 organizations lack the capacity to meaningfully engage in social media strategies in either an emergency or development context. Some simple tips and tools for integrating social and mobile media into the humanitarian response can be included in the toolkit and social media offers an excellent channel for dialogue with the community (where access is available) to increase accountability of humanitarian assistance processes. 3.17 The toolkits (both emergency and non-emergency focused) examined in this review identify the role of social and mobile media as channels of communication, but offer little concrete guidance on how channels such as social media can be mobilized. This is an emerging field and to date the debate concerning new ICTs and humanitarian assistance has centered on the aforementioned high-profile examples, but many smaller scale emergencies occur in countries that do not have the same levels of infrastructure or ICT access. Further, crowdsourcing data can lead to information overload and there is a concern within the literature over how the crisis mapping community and humanitarian assistance sector can more efficiently interact. Telecommunication systems are a critical backbone of many disaster responses, but often fail in the immediate aftermath of an emergency. While not over-hyping the role of new ICTs, the UNICEF toolkit will need to be alert to digital inequality issues, while promoting increased use of new ICT-driven tools and channels. New ICTs offer new ways of working, collecting data, sharing information and communicating alerts that current resources cover poorly. Recommendations: - Integrate role of new ICTs throughout the toolkit, especially in the areas of data collection, KAP and emergency SMS messaging (and other ICT channels). Do not build a separate section relating to new ICTs. Disaster Timeframes 3.18 Several of the emergency communication sources, including those from CDC and WHO, suggest a timeframe to emergency communication that are linked to service provision/response standards (a key aspect of accountability). WHO suggests a timeframe that reflects action in the immediate 12, 48, 72-hour period following an emergency, then again in the 5, 7, 15 and 60 day periods. During these periods different aspects of the disaster are addressed. CDC suggests a focus on the immediate 24 hours prior to the onset of a disaster (if possible), 1-3 days after a disaster, 3-7 days after, 1-4 weeks after and the one-month plus period. From a communications perspective these time frames help to divide responses between the rapid provision of generic warning messages to more specific messages that addresses issues (such as health, WASH, etc) in the period following the disaster. These messages (depending) on context, have the potential to link to rapidly collected behavioural/information needs data and have can have basic quality assurance measures such as pretesting and revision of messages/materials applied to them prior to dissemination. 3.19 The current BCC/C4D-focused resources do not focused heavily on differentiating their actions according to such timeframes and there is a limit to how prescriptive a toolkit can be in terms of trying to second-guess how an emergency will unfold (though there is merit in linking to examples identified in the literature review - see Ref. 5, page 80). To aid clarity of purpose, fewer rather than more phases would help make the UNICEF toolkit more accessible to users. The question of where the C4D/BCC adds value is important to a consideration of timeframes. Most C4D/BCC focused resources address the pre/post aspect of emergencies better than the acute emergency phase itself, which is more concerned with rapid information provision of often stock/generic messages. Where good preparatory work has been conducted context specific messages may already exist, however, humanitarian assistance tends to be reactive and good preparatory work tends not to occur. 3.20 BCC/C4D focused initiatives are perhaps more suited to chronic onset emergencies, such as civil unrest, long-term health crises or post-disaster/conflict recovery rather than acute emergencies/open conflicts. It could be argued that enough resources already exist to address the slow-onset communication dimension. What is currently lacking is a light version of 16 C4D/BCC that can be used during rapid onset emergencies and which adheres to minimum C4D/BCC standards. Within such a resource it may make sense to differentiate between different types of emergency, i.e. natural versus manmade. This could enable different types of communication to be prioritised within that are relevant to the issue at hand, i.e. warnings/take action for natural disasters versus dialogue for conflict reduction/peace-building. However, trying to make the UNICEF toolkit cover too many bases could be a significant error given the wide availability of high quality existing UNICEF and Red Cross BCC resources (see Ref. 10 and Ref. 7). Recommendations: - Chose a realistic emergency timeframe to ensure that fewer rather than more steps are included in the toolkit. The CDC 4-step cycle of 1-3 days after a disaster, 3-7 days after, 14 weeks after and the one-month plus period is more practical and is therefore preferable; - The toolkit should only cover acute/rapid onset emergencies (potentially divided between natural and manmade emergencies) and not try to cover more mainstream development processes. This will help focus the resource, help to partners, such as Red Cross and wide UN bodies and help keep the resource light. Ensuring Quality 3.21 Few of the formal emergency communication publications (the exception being the large CDC manual) advocate significant quality assurance measures. The generic nature of message giving and lack of focus on understanding behaviors or impacts works against a rigorous QA approach. The material that falls into the C4D/BCC category has significant sections on linking formative research to message development and the development and pretesting of communications materials. Ensuring that minimum standards for quality assurance are applied to emergency communication is important and this is where the toolkit will ‘add value’ to humanitarian assistance processes, i.e. be being light and lean enough to be used in practice. 3.22 Promoting clear communication effectiveness principles will also help to ensure that any message communicated are clear, relevant, do not offend or cause confusion. Sending confusing or inappropriate messages can harm humanitarian assistance processes and lead to a loss of trust in humanitarian organizations and weaken accountability. The review has identified a wealth of tools that can be developed and refined, into short simple guidance (see Refs. 2, 8 & 11). Recommendations: - Include simple QA tools throughout to aid message development and pretesting in particular. These can link to and support communication effectiveness principles to ensure that as users work through the toolkit they absorb some of the essence of what a C4D/BCC approach is concerned with. The resilience and accountably to affected populations agendas 3.23 The agendas of community resilience and accountability to affected populations are front and centre of UNICEF and the humanitarian community’s policy agenda. The CRS useful 9step toolkit is an excellent resource that directly speaks to the accountability issue and from which the UNICEF toolkit development can draw guidance. The AAP agenda brings and extra communication challenge as it is geared towards communicating the broad agenda of humanitarian assistance, rather than sectoral or thematic issues (where most of UNICEF’s focus resides). A simple toolkit is likely to be of practical use to a number of humanitarian agencies seeking to communicate aspects of their work in order to increase accountability. 3.24 The issue of resilience can be addressed at a broad principle level and commonsense 17 suggests that if communication promotes increases in KAP variables then an outcome could be increased community and/or individual resilience. However, few resources examined come close to making any such claim, though several reference the role of communication and information and a core protective asset were found (see Refs. 8 and 29). There is conceptual mileage in conceiving information and communication as a core protective asset for vulnerable people because it can function to lessen risk and promote protection (especially for groups such as children), which can then be linked to existing social protection message sets (see Ref. 8). A key question for the resilience approach to ultimately answer (though not in the context of the toolkit) is that if, as we know, behaviour change is subject to socio-cultural constraints, who is made more resilient and how? Is there inequality in the resilience built at community level and to whom does resilience accrue? Recommendation: - Include resilience as a brief framing theory that helps tie the wider humanitarian communication objectives together. Here resilience could be linked to the notion of communication as a protective asset. - UNICEF may want to further explore the concept of resilience in the context of C4D/BCC approaches to ensure that a rigorous data-driven link is established between communication and increased resilience, as it is a multifaceted asset that is potentially riddled with socio-cultural constraints. Accessibility of Existing Resources/Tools and Structure 3.25 The literature reviewed spans short and concise tools advocating varying numbers of practical steps (i.e. the CRS 9-step toolkit at 50 pages) to extremely long and detailed ‘how to’ manuals some of which extend to over 440 hundred pages (CDC see Ref. 5). UNICEF’s own BCC in Emergencies manual runs to 237 pages. In contexts characterized by conflict and rapid onset disasters the lengthier material is unlikely to be used as reference guides. Here speed and clarity are critical. The succinct CRS toolkit and the Annexes of the UNICEF Cholera Toolkit are an excellent place to start. UNICEF have an excellent body of C4D material and tools, the key is arrange them in an accessible format that is light, adheres to some core principles and is pragmatic, i.e. accepts that there is more value in formative research for message and content development, than seeking to prove behavioral impacts, which are time-consuming, risky in conflict zones and becoming increasingly difficult in contexts saturated with media and messages (making identification of a causal link problematic). 3.26 The best resources provide lists of questions and simple methodological tools and are geared towards a product (a strategy) being developed as a result of engagement with the resource, i.e. they ask question that demand answer and require users to complete sections. All toolkit-type resources examined are available in print or online as PDF documents. None examined offer a web or app-like experience. With the use of drop down menus that allow users to select the type of emergencies they are facing, unnecessary text on other types of emergency or generic messages can be excluded. Such an approach would help to make the user experience light, but may exclude users who only have access to a paper version. Many of the guides include a facilitator’s guide of some description, for workshopping the development of the strategy/plan. Others, such as the CRS guide, which is focused on the broad role of communicating humanitarian assistance, can be broken down into two documents one that contains a ‘super-light’ 9-step strategy development process that can stand alone, and one where it is included with supporting text. A web/app type document would allow users to engage in support material or ignore it depending on need/experience. 3.27 Consideration of the accessibility of existing resources inevitably results in a focus on who the audience/user of the toolkit will be. The current complexity and length of many existing emergency and non-emergency resources is likely to hamper their usability, though such data is difficult to find. Commonsense suggests the lightest and leanest resource will have most practical value, but a balance needs to be struck between ensuring relevance to the broader family of UN organizations, INGOs and NGOs. A light resource may also be of relevance to 18 community-based organizations. It is clear though that understanding the impact of technical resources is a low priority, as the dearth of evidence suggests. Because of this and the inability to second-guess who might use such a resource it is difficult to definitively state who the audience will be for the resource and this answer is likely to emerge through field-testing with a number of organizations. 3.28 Finally, the structure of existing resources is very much geared around highlighting communication effectiveness principles, providing question sets to guide strategy development, provision of message sets to aid initial communication, but also the provision of methodological tools and QA mechanisms to ensure that communication strategies are localized and made relevant to at risk populations. The existing UNICEF Cholera Toolkit annexes offer a good starting point (see Ref. 11). The literature review pinpoints a wide range of useful tools, graphics, methods and question sets that can be adapted for the UNICEF C4HA toolkit (see review table below). Recommendations: - Develop a paper and web/app version of the toolkit, both of which are geared towards the production of a defined emergency communication strategy/plan that can be adapted as needs change. This will ensure widest coverage of potential audiences; - Each section or step should have a consistent format, with: (i) communication approaches and principles; (ii) question sets that with help users generate answers that can be used to flesh out their strategies; (iii) simple methodological tools that enable these questions to be asked; (iv) simple quality assurance tools that help user ensure relevance. In addition, simple objective setting and M&E can be promoted, but with a preference for formative and pretesting work, rather than impact evaluation; - Limit the scale (i.e. no more than 30 pages for the ‘super-light’ tool and no more than 50 pages for the longer version) of the resource to ensure that it is light and focuses only on the essential methods, tools, principles and quality assurance mechanisms; - UNICEF might want to consider undertaking a separate assessment of how its wider body of C4D resources is used and adapted at the local level as a way of understanding how to communicate technical advice going forward. Lessons emerging from academic literature 3.29 Rather than examine a wide body of academic literature this review - for the sake of efficiency and timeliness - examines the findings emerging from the comprehensive review of C4D Interventions in Fragile States (Ref. 22) undertaken by the author (Skuse) and summarised here. The goal of the review was to identify the range of contextual and programmatic factors that frame, affect and constrain communication for development (C4D) interventions undertaken in fragile or conflict affected states. Understanding the various factors that influence C4D interventions in fragile states is important to improving practice, implementation and evaluation, as well as to the future development of methodologies and frameworks that can be utilised in conflict or crisis situations. 3.30 The review examined a total of 239 sources, of which, 156 of these were excluded leaving 83 sources that were assessed for methodological quality. A total of 26 papers (19 qualitative papers and 7 opinion pieces) were included for full review and data extraction. Following extraction, a discussion was developed that examined the relevance of the findings from a realist perspective. 3.31 The review identified that while different initiatives can be pursued in different conflict or humanitarian situations, a close understanding of context and the factors that can both positively and negatively influence communication should drive their direction and content. While identifying influencing factors that affect C4D implementation is critical to effective practice, the systematic review also highlights a need for early, more thorough and longer-term 19 C4D interventions within fragile states (especially those that can be characterised by latent conflict and chronic instability). Early communication intervention can help reduce tension and promote reconciliation, but also enable development and humanitarian agencies to be better placed to address situations that may escalate into open conflict. The full list of programmatic and contextual factors is broken down within the review into: (i) identified frameworks, theories or approaches; (ii) facilitators; (iii) obstacles; and (iv) outcomes. These are summarised below. Framework Facilitators Obstacles Outcomes - Behaviour change communication (BCC) - C4D - Capacity strengthening - Civic education - Media strengthening - Edutainment - Participatory approaches - Culturally appropriate media content - Understanding the cultural context - Understanding the institutional context - State media - Telecommunications - Multi-channel communication - Participatory media - Sustainability planning - Long-term commitment - Building digital or media literacy - Gender equality - Local ownership - Local participation - Contextual constraints - Digital divide - Information divide - State media - Media bias - Hate media - Weak evidence - Conflict reduction - Peacekeeping - Reconciliation - Dialogue - Social action - Behaviour change 3.32 The findings of this review of mainly academic literature supports the need for C4D in humanitarian or conflict situations to seeks to adhere to basic C4D effectiveness principles and practices wherever possible, even if this in a slimmed down form. The literature highlights that effectiveness and therefore impact is generated when a significant commitment, especially to generating formative assessments of context is pursued. Many similar principles are reflected in the organisational literature on emergencies examined below (see Annex 1) in this respect the humanitarian/development literature and academic literature support each other. Recommendations: - The toolkit development process must ensure that the various factors identified in the review of academic literature are supported in the outputs and that identifying supporting frameworks and clear outcomes resulting from communication is important. 4. Conclusion 4.1 This review has covered a body of evidence derived from organisations with a mandate for humanitarian protection and the delivery of assistance. It has made a number of findings and recommendation that are set out in full in the Executive Summary and are not repeated here. The objective of the review was to identify what existing approaches and tools tell us about how a concise and practice focused Communication for Humanitarian Assistance Toolkit might be developed. The annex set out below provides a wealth of data and examples that can be drawn out and included in the toolkit. Finally, a number of limitations were associated with this review. The brief timeframe allocated to the review meant that it was necessary to focus on practice literature only and literature that was current. 20 Annex 1: Summary of Included Literature 4 Title, Author and Link Accountability to Affected Populations, Inter-Agency Standing Committee. Year 2013 http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_uploa d/emergencies/docs/IASC%20AAP%20 Operational%20Framework%20March %202013.pdf Focus Role of communication in promoting accountability to disaster-affected populations. Assessment This resource is an operational framework that seeks to promote greater accountability in the delivery of humanitarian assistance. There is a specific focus within the framework on communication (objective 2) and especially on the need for better integration of communication into relief initiatives to promote awareness of aid delivery objectives, as well as on the scaling of emergency/risk reduction communications. Though not offering a specific tool, the essence of the framework is best captured in the CRS nine-step toolkit, which provides a solid design pathway for developing communications that help build accountability with affected populations. Papers/resources not subject to full review 26 Why Dialogue Matters for conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding, UNDP. 2009 Focused on the role of dialogue with conflictaffected populations. Not subject to full review. Has no explicit focus on communication but notes the need for dialogue and links can be drawn to recent work on communication and the role of accountability for disaster-affected populations. 2009 Focus on role of media and journalism in conflict. Not subject to full review. This resource provides a useful analysis of the media context in Pakistan, its strengths, weaknesses and its legislative status. It addresses important media strengthening issues around media bias and quality. Media strengthening features weakly within emergency communication literature yet plays a critical role in ensuring an effective and robust environment. 2013 Global and local public health emergencies This document sets out a framework for grading and responding to the health aspects of emergencies, such as rapid onset disasters. The document proposes ongoing risk/event assessment and a grading of emergencies from ungraded, to levels 1, 2 and 3, with 3 being the most severe. Pages 23-26 set out some useful time bound performance standards that links WHO to certain response standards in the immediate 12, 48, 72 hour period following an emergency, then again in the 5, 7, 15 and 60 day periods. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/ crisis%20prevention/dialogue_conflict.pdf 27 Between radicalisation and democratisation in an unfolding conflict: Media in Pakistan, International Media Support. http://www.i-m-s.dk/wpcontent/uploads/2012/11/ims-media-pakistanradicalisation-2009.pdf 28 Emergency Response Framework, WHO http://www.who.int/hac/about/erf_.pdf 21 29 Basic Resilience Package: The ‘How-to’ Guide for Child Survival and Development Programs, UNICEF 2013 No weblink available. Emergency and development focused. Multifaceted assessment of resilience. UNICEF’s forward strategy (2014-17) proposes a resilience approach to its work in humanitarian assistance and development. In the area of C4D and child survival and development programs this includes a focus on: - Increased awareness and knowledge on risks and available solutions; Addressing underlying issues compounding risk; Participation of communities, children and young people in policy/ programming. From the resilience perspective information and communication helps to reduce risk and vulnerability and, along with other assets and forms of capital, can be perceived as an essential protective asset that contributes to individual and group resilience. 30 Core Commitment for Children in Humanitarian Action, UNICEF http://www.unicef.org/mena/MENACCC_final.pdf 2010 UNICEF’s broad program commitments to populations in emergencies. UNICEF’s core commitments for children during emergencies and humanitarian action covers the broad range of activities and responsibilities that UNICEF fulfil within such contexts. The resource identifies some useful references to humanitarian action principles and the role of rights (pages 6-7). There is a useful section on rapid assessment, monitoring and evaluation that covers preparedness, response and recovery. Sections on the thematic areas in which UNICEF works, i.e. HIV, WASH, etc. provide useful summaries and are followed by a consideration of resource inputs to humanitarian action, including HR, logistics, risk and so on. 22