Word format - Stephen Hicks, Ph.D.

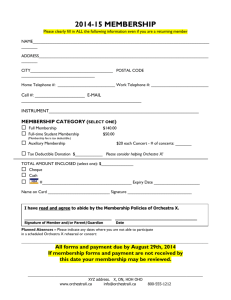

advertisement