Wolfgang Wildgen (Universität Bremen) Minimal syntax: comparison

advertisement

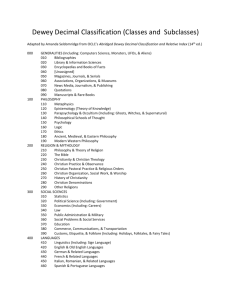

Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Wolfgang Wildgen (University of Bremen) Meaning Construction in Modern Poetry: Paul Celan Conference at the Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland (USA); German Studies and Center for Cognition and Culture 8th of October.2007; 4:30 in Clarke 206 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Contents Part I: Language crisis and Paul Celan’s poetry Part II: The neuro-cognitive basis of meaning-composition and its relevance for creative poetry 2 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Part I Language crisis and Paul Celan’s poetry Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Language crisis and poetic discourse • One standard assumption in linguistics is that language is a kind of common good like the air we respire or the water we drink. It is not owned by some people, some groups or institutions; it is not shaped for their interests, to their advantage; in one word it is neutral. • However since the French revolution and more recently during the World wars the assumed neutrality of language is endangered. Political ideologies, ideological wars, psychological warfare have broken this ethical principle. A political party, which is able to control major content spaces and their expression in spoken discourse and in the media, may be able to manipulate the users of a language. • In political practice a mixture of seduction, repression of specific media or speakers, and an intensive propaganda may for some period fool an important part of the population. 4 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures • The German philosopher Ernst Cassirer, who had to emigrate in 1933 (because he was Jewish) wrote in 1944 that in reading German texts and hearing German broadcasts he could no more understand properly these discourses. It seems difficult to explain this experience in linguistic terms. The reason is that the semantic unity of languages assumed by linguistic theories is an illusion. • If a very strong and enforced ideological movement affects a large part of the society, the space of the personally experienced meanings can be polarized and heavily biased in one direction. How should an intellectual who uses the language in question (in this case German) professionally react? Cassirer learned to write in English and published his later books: The Myth of the State, An Essay on Man, in English. Heinrich Heine who was a German poet began to write poems in German and in French when he was (for his lifetime) exiled in Paris. In both cases giving up a language in which one had been thinking and writing in the constitutive period of one’s biography was dramatic and highly problematic. 5 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures • Paul Celan continued to write poems in German after his emigration to France. Thus the corruption of the German language was a phenomenon he had to reflect, although the situation had changed after 1945 (but he was very attentive to persons who continued their career in spite of their involvement with the Nazi-regime, like Heidegger). • Celan made a comment on the loss of language: »Erreichbar, nah und unverloren inmitten der Verluste blieb dies Eine: die Sprache. Aber sie mußte nun hindurchgehen durch ihre eigenen Antwortlosigkeiten, hindurchgehen durch furchtbares Verstummen, hindurchgehen durch die tausend Finsternisse todbringender Rede. Sie ging hindurch und gab keine Worte her für das, was geschah. Aber sie ging durch dieses Geschehen.« cf. Celan, 1983: 185f. • (“Accessible, near and not-lost in the mid of all these losses stayed the one: Language. But it had to go through, go through its own lack of answers, go through a terrible silence, go through thousand darknesses of deathbringing speech. It went through and did not bring words for that which happened. But it went through all this happening.” Translation by W.W.) 6 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures The poet Paul Celan (his family name was Anschel) was born in Czernowitz (Bukowina) in 1920. He went to Paris in 1938 to study medicine but returned to Czernowitz in 1939. He stayed in Rumania until 1947 when he fled to Vienna and 1948 came to Paris to study German Linguistics and Literature. In 1959 he became lecturer (lecteur) of German at the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in Paris. After 1961 he had to be treated in different psychiatric clinics. He committed suicide in Paris 1971. 7 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Compounds in experimental poetry: analysis of some compounds in poems by Paul Celan (1920-1971) Titles of collections: quantity - Mohn und Gedächtnis (1952) 56 poems - Von Schwelle zu Schwelle (1955) 47 " - Sprachgitter (1959) Die Niemandsrose (1963) Atemwende (1967) Fadensonnen (1968) 31 53 80 105 " " " " - Lichtzwang (1970) - Schneepart (1971) 81 70 " " - Lichtgehöft (1976) 50 " 8 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Nonce-compounds as minimal utterances in titles of poem books by Paul Celan Sprachgitter : Niemandsrose: Atemwende : Fadensonnen: Lichtzwang : SG NR AW FS LZ (Speech-Grille) (The No-One’s Rose) (Breathturn) (Threadsuns) (Light-Compulsion; Force of Light) Schneepart : SP (Snow−Part; Snow-Voice) Zeitgehöft : ZG (Homestead of Time) (The translations are from: Celan, 1971 and 2001) 9 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Final titles und proposed titles Atemwende Fadensonnen Atemzeile; Wahnspur; Atemkistall; Wahn, Atem: Wahn, Atem Sinnfäden; Die Freistatt (refuge); Fadensonnen; Findlinge; Fadensonnen 10 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Similar compounds in the Celan corpus (language/word) Sprache (Language) as first constituent Sprachwaage(NR) : language-weighing machine Sprachtürme (AW) : language-towers Sprachnebel (LZ) : language-mist/fog and with Wort (word): Worthöhlen (LZ) : word-caves Wortwaage (NR) : word-weighing machine Wortspur (AW) : word-track/trace Wortwand AW) : word-wall Wortsand (NR) : word-sand Wortwege (NP) : word-lanes Wortlitze (SP) : word-braid Wortschatten (SP) : word-shadow 11 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Possible readings of Sprachgitter If we start from the list of relational schemata (or semantic archetypes), we obtain the following possible readings: 1. a grille/grid is language or vice versa 2. a grille/grid makes language end/begin 3. a grille/grid captures/absorbs/destroys language 4. a grille/grid creates/generates language 5. a grille/grid transmits/filters language 6. a grille/grid instrumentally affects language (cutting it off or binding it together) The fact that a list of alternatives with growing complexity exists explains the power of integration of such a title. It may stand as an abstract of the poems which make up the book of poems or the stanzas/lines in a poem. 12 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Distribution of heavy/central and restrictive/peripheral constituents heavy constituent (pivot) light constituent (restrictive) Sprachgitter Sprache (language) Gitter (grille/grid) Niemandsrose Rose (rose) Niemand (nobody) Atemwende Atem (breath) Wende (reversal) Fadensonnen Sonne (sun) Faden (thread) Lichtzwang Licht Zwang (compulsion) Schneepart Schnee Part (part) Zeitgehöft Zeit Gehöft (group of farmbuildings) 13 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Proliferation from the titles to the poems In the collection: Atemwende we find: • Atemseil (breath-rope) • Atemkristall (breath-crystal) • Steinatem (stone-breath) In the other collections similar compounds based on breath show up: • Niemandsrose : Atembau (breath-fabric) Atemmünze (breath-coin/cash) • Schneepart : Atemnot (shortage of breath) The continuous breath (standing for life/soul) is broken down to limited forms or is lacking (Atemnot) 14 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Further principles Key words of the author, which are statistically prominent (high recurrence) sketch the semantic frame of the poetry in question; Simple binary binding patterns between head and satellite, predicted by the hierarchy of semantic archetypes, occur. Examples: • part of (in Schneepart), • assembly (of farm buildings as in ZeitGehöft) • thread (Faden) as opposed to disk (Scheibe) or body • negation, nobody (niemand) • barriers: grille/grid (Gitter) • antagonistic actions: reversal (Wende), compulsion (Zwang) 15 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Analysis of two poems by Celan Aspen Tree, your leaves glance white into the dark. My mother's hair was never white. Dandelion, so green is the Ukraine. My fair-haired mother did not come home. Rain cloud, do you linger at the well? My soft-voiced mother weeps for all. Round star, you coil the golden loop. My mother's heart was hurt by lead. The poem Aspen Tree (cf. Celan, 2001: 21). Oaken door, who hove you off your hinge? My gentle mother cannot return. 16 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures The poem has five stanzas and each one begins with a minimal utterance, either a compound or a noun phrase: • Aspen tree (Espenbaum) • Dandelion (Löwenzahn = lion tooth) • Rain cloud (Regenwolke) • Round star (Runder Stern) • Oaken door (Eichne Tür) The first line is always completed by a sentence, two of them being questions. The second verse of each stanza has “my mother” as recurrent topic. 17 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures A photo of Celan’s mother in 1915 he whistles for the Jews has a grave shoveled in the earth he orders us now to strike up the dance (Death Fuge) 18 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Todesfuge (Deathfugue): Beginning of the poem: 1952 Black milk of daybreak we drink it at nightfall Weiße Milch we drink it at noon in the morning we drink it at night drink it and drink it Sprachgitter (language grille): Beginning of the poem: 1959 Augenrund zwischen den Stäben. Eye-round between barrows Flimmertier Lid rudert nach oben, gibt einen Blick frei. Cilium-animal eye lid Iris, Schwimmerin, traumlos und trüb 19 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Analysis of the compounds In the new poems (after Celan’s move to Paris), the compounds are nonce compounds and in general enigmatic: • “Todesfuge” (Todestango) refers to a piece of music (Fuge/Tango/ …) and associates it with death. Coexistence (or precedence) in time of music playing and killing in the concentration camp. • “Eye-round” is like a nonce transformation of “round eye” with an inversion of word order. • “Cilium-animal” could be a real animal, but the immediately following “Lid” (lid) shows that the compound describes metaphorically a body part following the schema: body parts are animals. In general very basic types of association (binding; cf. next section) are used to give meaning to the compounds. 20 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Attractors on lexical fields: the “Meridian” • In a real time meaning construction different phases may be distinguished. If we imagine the poet sitting in front of a white sheet of paper, he starts from an opaque basic intention, an impulse connected to a series of emotional and intellectual states. This phase is unconscious and mostly inaccessible to analysis. Before the first word or strophe is conceived a kind of conceptual search or an itinerary through conceptual space takes place. This phase is still rather opaque, but Celan gave a name to this search in a landscape. He called it a Meridian. • He conceives the conceptual space of his poetry as a globe and the poet has lines, circular path-ways on this internal globe for his orientation. In the context of a dynamic theory of language we can call the meridian an attractor, i.e. the search for concepts will again and again meet this field of attraction. 21 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Itinerary of topical search In three-dimensional space, the attractor could be a circular path on a torus or a sphere. If the attractor begins to move also, we obtain a “strange” attractor ; the behavior of the system becomes chaotic. Loosing one’s meridian explains the loss of psychic control. Therefore “finding one’s meridian” is necessary for mental health Meridian attractor 22 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures The “Meridian” • “Something – like language – immaterial; yet earthly terrestrial, something circular, rejoins izself itself after having crossed both poles and which – serenly crosses the tropics-: I find … a meridian.” (translation by W.W. of:“etwas - wie die Sprache – Immaterielles; aber Irdisches, Terrestrisches, etwas Kreisförmiges, über die beiden Pole in sich selbst zurückkehrendes und dabei - heitererweise - sogar die Tropen Durchkreuzendes - : ich finde einen Meridian“) • With the “tropes” Celan means at the same time the tropical zones and the thematic, topical domains called “tropes” in classical rhetoric. Definitions: Meridian (geography): either half or a full great circle that connects the Earth's poles. (Chinese medicine) Any of the longitudinal pathways on the body along which the acupuncture points are distributed. 23 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Conclusion of Part I • As a first conclusion we may say that the meaning universe of his poems is structured first by global attractor(s), such as the meridian, and secondly by thematic lines and networks. This structure is clearly non-propositional, it does not imply a syntax in the usual sense. On the contrary if syntax is seen as the automatic rule governed generation of language as by an automaton, this is just what Celan’s poetry is not. He says himself in his Büchner talk: • “vielleicht versagen hier die Automaten – für einen einmaligen kurzen Augenblick” (translation by W.W.: Perhaps will the automatons – for one singular and short moment- be not working“. • In a sense, Celan’s poetry and probably other experimental poetry as well, is anti-propositional and antisyntactic - although this is only feasible in the limit. 24 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Linguistic analysis of poetry? • Sentences or propositions can be positively accepted or negated, in modern terms they receive a truth value, whereas words and phases do not. Thus the sentence level is the main level where complex meaning-gestalts can appear and it is the truth value which makes the unity of this Gestalt. For Aristotle this was important because he could build his syllogistic machinery on unities which are mainly characterized by their truth value (besides quantification: all, some). • This advantage is still valid for argumentative discourse, and in a narrative discourse inferences may play a role, although force dynamics, space and time continuities are more important. • In the case of poetry this machinery is rather irrelevant. As a consequence a type of analysis based on propositional semantics is not of great use. We will therefore go back to more basic operations. 25 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Part II The neuro-cognitive basis of meaning-composition and its relevance for creative poetry Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Nominal compounds and bare nominal groups as minimal utterances If we take a compound as a kind of utterance per se, outside of its possibly complex syntactic and textual context, its constituents are often conceptually simple (e.g. stems/radicals). Although these morphemes may belong to specific syntactic classes of the language in question, this feature has only a reduced significance for the construction of the meaning of the compound, i.e. the syntactic potential of the morpheme is dormant in the compound construction. In the case of adjective+ noun and similar constructions, the way of semantic composition is comparable to that of compounds. 27 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Temporal binding in the brain as basic compositional operation • The binding process is one of temporal synchronization of neural assemblies, which form wholes (gestalts) from parts and one of desynchronization which distinguishes figure and ground. • This type of analysis concerns primarily the composition in perception, attentiveness and memory, but one may conjecture a parallel process for words (at least those related to perceptual information) and their composition in syntactic constructions. • Temporal binding of neurons could be the elementary semantic operation by which new conceptual entities are created in poetry. 28 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures The basic idea of temporal binding Parts or features of a visual whole are linked by the synchronic firing of a set of neurons (an assembly) during a short time interval. In the example the parts and features of the cat and those of the woman are bound together by the internal synchrony of the assemblies 1 and 2 and they are distinguished by the asynchrony of these assemblies. From: Engel et alii, 1997: 572 29 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Ambiguity and Binding Picture a is ambiguous. If it is seen as one face (and a candle in front of it) the zones (1,2) and (3,4) (see series d) are bound; in the case two faces looking at each other are seen, the zones (1,3) und (2,4) are bound. The binding may be recognized by the synchronic firing rates in the series d versus e. From: Engel, Fries und Singer, 2001: 707 30 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Top down effects due to expectation and memory The remembered object produces higher synchronization at the γ-level (30 to 60 Hz) At the left a Kanitza-triangle At the right a non-Kanitza-triangle If the tested person is instructed to recognize the non-Kanitza-triangle , the synchronization is higher for this configuration, although basic gestalt laws would predict the contrary. From: Hermann, Munk und Engel, 2004:349 31 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Binding and nominal composition • The first constituent in the nominal compound, N1, allows for a certain class of predicates/prepositions and N2 also has such a class of possible predicates. The compound N1 + N2 can activate the product (set of pairs) of possible predicates. The search for one or a few stable readings can be described as an orbit in the space of N1xN2. In a neurolinguistic perspective we can say that the brain has simultaneously access to a huge amount of possible predicate-pairs, it is in a state of "predicate alert". The binding process selects one reading which makes sense and thus synchronizes N1 and N2 in a selective way. Other choices may be repressed (no synchronization); cf. Wildgen, 1994. 32 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Why is temporal binding relevant for experimental poetry? • In a poem, the author must after the stage of unconscious orientation in his tropes-space (seeking the “Meridian”) find the proper words fitting his conceptual search. He either hits at a proper word directly or he must create a compound, which corresponds to his expressive goal, out of given words. The spontaneous creation of nonce compounds is a solution to this problem. • However, the results of such a composition are not regulated by a conventionalized lexicon, they rather correspond to a spontaneous brain activity of the type we have described in the last paragraphs. 33 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Questions • How can the ambiguity of such nonce compounds be controlled? Are they able to create a richer field of possible interpretations? • Will the hearer/reader be able to reconstruct the cognitive pathway of the author or will he at least come to a similar experience? • How will the space of solutions to the problem of interpretation be coordinated with the interpretation of the words, phrases and sentences which stand in the context of the compound; i.e. will the compound properly contribute to the global meaning of the text? 34 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Precision but not clarity • In the poem the restrictions on logical or force-dynamic and spatial consistency are not the same as in argumentative or narrative texts. Therefore the possible divergence between results of the construction intended by the author and reconstructed by the reader/hearer does not dramatically endanger the poetic text. On the contrary, Celan cites Pascal, a very geometrically minded French philosopher of the 17th century, who said: • “Ne nous reprochez pas le manque de clarté, car nous en faisons profession » (translation by W.W.: Do not reproach us the lack of clarity, because we intend it) 35 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures • Nevertheless the poet does his best to be precise, to come the nearest he can to his expressive goal. The lack of clarity is just the consequence of the fact that the poetic text is not argumentative and thus does not have to follow the rules of logic; it is not narrative, and thus the spatial/temporal/causal unity is not its primary goal. • The poem is precise in articulating the flow of meaning and feeling beyond strictly conventional rules and thus it can establish a more direct link to private and personal thinking and feeling. • The mystery is: How does this meaning beyond rigid conventionality become accessible to readers who do not share the private meaning space of the author. In fact poetic communication stands always at the rim of non-communication, silence of response. At the same time this makes the essential value of this type of risky communication visible. 36 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures Bibliography • Celan, Paul, 1986. Last Poems (translated by Katherine Washburn and Margret Guillemin), North Point Press, San Francisco. • Celan, Paul, 1996. Die Niemandsrose : Vorstufen - Textgenese Endfassung (bearb. von Heino Schmull unter Mitarb. von Michael Schwarzkopf; hrsg. Von Schmull, Heino ; Schwarzkopf, Michael) ; Wertheimer, Jürgen), Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main. • Celan, Paul, 2000. Glottal Stop. 101 poems by Paul Celan (translated by Nicolai Popov & Heather Mc Hugh), Weleyan Universiy Press (University of New England Press), Hanover&London. • Celan, Paul, 2001. Selected Poems and Prose by Paul Celan, Norton, New York. • Celan, Paul, 2004. Mohn und Gedächtnis. Vorstufen-TextgeneseEndfassung (bearbeitet von Heino Schull unter Mitarbeit von Christiane Braun), Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main. 37 Center for Theory of Language and Semiotics Faculty: Languages and Literatures • Nielsen, Karsten Hoidfelt and Herald Pors, 1981. Index zur Lyrik Celans, Fink, München. • Pors, Harald, 1989. Rückläufiges Wortregister zur Lyrik Paul Celans, Fink, München. • Fleischer, Michael, 1985. Nomenhäufigkeitsverteilungslisten zur Lyrik von Paul Celan. Statistik der Substantive und ihrer Komposita, Verlag: Die Blaue Eule, Essen. • Wildgen, Wolfgang, 1982. Zur Dynamik lokaler Kompositionsprozesse. Am Beispiel nominaler ad hoc-Komposita im Deutschen, in: Folia Linguistica, 16: 297-344. • Wildgen, Wolfgang, 1987. Dynamic Aspects of Nominal Composition, in: Ballmer, Thomas T. and Wolfgang Wildgen (eds.), 1987. Process Linguistics, Niemeyer, Tübingen: 128162. • Wildgen, Wolfgang, 1994. Process, Image, and Meaning, Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: mainly Chapter 4. 38