sps165 - Myweb @ CW Post

advertisement

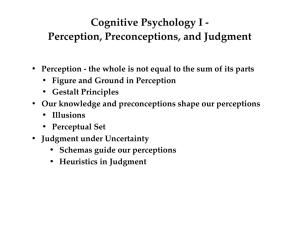

. Introduction to Social Cognition We are always trying to make sense of our social world Social Cognition is: How people think about themselves and the social world How people select, interpret, remember, and use social information to make judgments and decisions How Do We Make Sense of the World? When we try to make sense of our social world, are we rational? One view is that we are completely rational; we do our best to be right and hold correct opinions or beliefs Most of us tend to consider ourselves as being highly rational Another view (supported by the research) is that we take shortcuts whenever we can How do we make sense of the world? Bentham (18th century) thought we were purely rational He thought people consider all of the options, then make the choice that will result in the most happiness (felicific calculus) Kelly (1960s) also thought we are purely rational He believed that people act as naïve scientists: essentially gathering data before we come to a decision such as whether others act in a certain way However, accurate data are not always available, and we don’t usually have the time to weigh all possible evidence before making decisions How do we make sense of the world? Fiske and Taylor (1991) realized that we are actually not so rational! Cognitive misers: people are always trying to conserve our cognitive energy by ignoring some information, overusing other information, and being willing to accept a less than perfect alternative that is good enough This strategy allows us to make decisions efficiently, but it can also lead to serious errors and biases, especially when we select an inappropriate shortcut or ignore important information when we’re in a rush Effects of Context on Social Judgment Because we are cognitive misers, we use the social situation as shortcuts to making decisions Thus, how we think about people and things depends on the social context (i.e., the way things are presented and described) 4 aspects of the social context affect our judgment: Comparison of alternatives (reference points and contrast effects) The thoughts brought to mind by a situation (priming and construct accessibility) How the decision is framed or posed The way information is presented (order and amount of information) Effects of Context on Social Judgment: Reference Points and Contrast Effects Contrast effect = when an object is contrasted with something similar but not as good, that particular object is judged to be better than would normally be the case For example, when a realtor takes you to an over- priced crappy apartment, the next apartment will look better to you than it would have had you not seen the crappy apartment first Kenrick & Gutierres (1980): When men watched Charlie’s Angels before going out on a blind date, they rated their dates as less attractive than when they watched the show after going on the date! Effects of Context on Social Judgment: Reference Points and Contrast Effects Can judgments we make about ourselves be influenced by contrast effects? Yes! High school valedictorians experience a dip in self-esteem after starting at an elite college where everyone was the valedictorian – now they are average (Marsh et al., 2000) People rate themselves as less attractive after seeing images of attractive people (Thornton & Maurice, 1997) Effects of Context on Social Judgment: Priming and Construct Accessibility Our interpretation can depend on what happens to be prominent in the situation What is prominent can be induced through priming: exposing someone to a concept or an idea before the situation that you are interested in Priming = a procedure based on the notion that ideas that have been recently encountered or frequently activated are more likely to come to mind and thus will be used in interpreting social events See the next slide for an example of how this works! Effects of Context on Social Judgment: Priming and Construct Accessibility Priming plays a role in the formation of impressions about other people Participants were told they were in two separate studies, and in the first one, they had to remember either positive (e.g., adventurous, self-confident) or negative trait words (e.g., reckless, conceited) – in reality, this was to prime them to think about these traits! In the “second study,” participants read an ambiguous paragraph about Donald Then participants described Donald in their own words and rated how desirable they considered him to be Results: how they were primed influenced their impressions of Donald – those who had memorized positive words described him more positively, and those who had memorized negative words described him negatively (Higgins, Rholes, & Jones, 1977) Effects of Context on Social Judgment: Priming and Construct Accessibility Priming also affects our own behavior Participants had to unscramble jumbled up words that were associated with rudeness or were neutral words (thus, they were primed to think of rudeness or not) Then, they were told to get the experimenter in the next room when they finished They found the experimenter deeply engaged in a conversation Those participants who were primed with words associated with rudeness were far more likely to interrupt the experimenter’s conversation! (Bargh et al., 1996) Effects of Context on Social Judgment: Framing of the Decision Framing = whether a problem or decision is presented (framed) in such a way that it appears to represent the potential for a loss or for a gain People dislike losses and seek to avoid them (e.g., it’s more painful to give up $20 than it is pleasurable to gain $20) Gonzales et al. (1988) Energy experts gave homeowners a detailed, individualized description of how much money they could save (condition 1) or how much money they had lost (condition 2) on their heating bill due to poor insulation Homeowners in the loss condition were twice as likely to invest the money to insulate their homes as those in the save condition Effects of Context on Social Judgment: Presentation of Information The order of information matters! Primacy effect = the things we learn first about a person have a decisive impact on our judgment of that person This is why first impressions matter a great deal Asch (1946) had participants read one of the following two sentences: Steve is intelligent, industrious, impulsive, critical, stubborn, and envious Steve is envious, stubborn, critical, impulsive, industrious, and intelligent They rated Steve more positively when they read the first sentence, even though the sentences contain the same information! 2 explanations for the primacy effect: Attention decrement = items presented later in the list receive less attention as we tire and our minds wander Interpretive set = first items create an initial impression that is then used to interpret subsequent information Effects of Context on Social Judgment: Presentation of Information The amount of information given also matters Dilution effect = the tendency for neutral and irrelevant information to weaken a judgment or impression Zukier (1982) had participants read one of these sentences: On average, Tim spends about 31 hours studying per week Tom spends about 31 hours studying outside of class in an average week. Tom has one brother and two sisters. He visits his grandparents about once every 3 months. He once went on a blind date and shoots pool about once every 2 months. Those who read the first sentence thought Tim was smarter! Advertisers know that including a weak/irrelevant claim can reduce the impact of a strong sales appeal Disliked politicians can reduce the impact of their negative image by including irrelevant information in campaign ads Judgmental Heuristics Judgmental heuristics = mental shortcuts; they are simple, often only approximate, rules or strategies for solving a problem (remember: we are cognitive misers) Heuristics require little thought; they can be contrasted with more systematic thinking in which we look at a problem from a number of angles, evaluate as much information as possible, and work out the implications of various solutions Examples: If a particular food is found in a health food store, it must be good for you If a person is from a rural town in Arkansas, he or she must be intellectually backward Three most common judgmental heuristics: Representative heuristic Availability heuristic Attitude heuristic Judgmental Heuristics: The Representative Heuristic When we use the representative heuristic, we focus on the similarity of one object to another to infer that the first object acts like the second one (Kahneman & Tversky, 1973) Example: We’d assume Quaker’s 100% Natural Granola is more nutritious than Lucky Charms because we use the package as a representative heuristic Quaker’s 100% Natural Granola box looks natural, which we equate with good and wholesome, so the cereal must be nutritious Lucky Charms box looks childish and, since kids like junk food, the cereal must be junk Judgmental Heuristics: The Representative Heuristic VS. Judgmental Heuristics: The Representative Heuristic If you look closely at the article above, you can see that it is the Lucky Charms that actually have less fat and sugar as well as fewer calories and carbohydrates! Granola has more fiber and protein, but overall, Lucky Charms is actually healthier! This has been demonstrated in studies of rats – they do better on Lucky Charms! Judgmental Heuristics: The Availability Heuristic Availability heuristic = judgments based on how easy it is for us to bring specific examples to mind If you ask people to estimate the number of violent crimes committed each year in the US, people who watch prime-time TV news believe violent crimes are far more common than people who don’t watch primetime TV news It’s easier to bring to mind examples of deaths from sharks and fires because these events are more likely to be covered in a vivid manner on the news and thus are more available in people’s memories (Plous, 1993) So people think these events are more common than they actually are! Judgmental Heuristics: The Attitude Heuristic Attitude = an enduring evaluation of people, objects, and ideas that contains both an: Evaluative/emotional component Cognitive component Attitudes can be positive, negative, or mixed evaluations expressed at some level of intensity; Like, love, dislike, hate, admire, and detest are some words people use to describe their attitudes Attitude heuristic = making decisions based on a preexisting attitude about a certain issue or situation Pratkanis (1988) found that if you liked President Reagan, you were more likely to believe that he had an A average in college than if you disliked him, in which case you were more likely to believe he had a C average in college (He really had a C average, but study participants did not know that) Judgmental Heuristics: The Attitude Heuristic Halo effect = a general bias in which a favorable or unfavorable general impression of a person affects our inferences and future expectations about that person Example: once people found out that a woman ate healthy food, they rated her as more feminine, more attractive, and more likable than junk food eaters (Stein et al., 1995) We also tend to think that more attractive women are also smart and have a lot of other positive qualities False-consensus effect = a tendency to overestimate the percentage of people who agree with us on any issue If I believe something, I leap to the conclusion that other people feel the same way Example: college students who agreed to wear an “Eat at Joe’s” sign around campus thought that others would too Judgmental Heuristics: When Do We Use Them? We don’t always rely on heuristics to guide our decisions Heuristics are most likely to be used when: We don’t have time to think carefully about an issue We are too overloaded with information to process the information fully The issues at stake are not very important (we don’t care to spend much time thinking about it) We have little solid knowledge or information to use in making a decision Categorization and Social Stereotypes We categorize persons and events all the time; the consequences of how we interpret and define events can be significant A major consequence of categorization: it can invoke specific data or stereotypes that then guide our expectations Examples: Once we categorize a person as a “party girl,” we base our expectations about future interactions on that stereotype If I go into a café that a friend categorized as a “bar” as opposed to a “fine dining establishment,” I’ll think of the place in a certain way and act in a certain way Self-fulfilling prophecy = the process by which expectations or stereotypes lead people to treat others in a way that makes them confirm their expectations If a teacher is told a student is not smart at the beginning of the school year, this student is likely to underperform, probably in part due to the teacher’s treating them as if they are not smart Categorization and Social Stereotypes Another consequence of categorization: illusory correlation Illusory correlation = we frequently perceive a relationship between 2 entities that we think should be related, but in fact they are not Example: People consistently overestimate the extent to which lesbians are likely to contract the AIDS virus In fact, lesbians have a lower rate of HIV infection than male homosexuals and male and female heterosexuals This is an example of the illusory correlation (see next slide) Categorization and Social Stereotypes High rates of HIV among male homosexuals Mistaken judgment that lesbians are more likely to have AIDS Lesbians are homosexuals Categorization and Social Stereotypes In clinical judgments, categorizing an individual into a certain diagnostic category (e.g., schizophrenic) can lead to the perception of a relationship (even when none exists) between the individual and behavior associated with the diagnosis The illusory correlation does much to confirm our original stereotypes Our stereotype leads us to see a relationship that then seems to provide evidence that the original stereotype is true Categorization and Social Stereotypes One of the most common ways of categorizing people is to divide them into 2 groups: Those in “my” group (ingroup) Those in the “outgroup” Examples: My school vs. yours Us vs. them My sports team vs. the opponent Americans vs. foreigners My ethnic group vs. yours Consequences: Homogeneity effect Ingroup favoritism Categorization and Social Stereotypes Homogeneity effect = we tend to see members of outgroups as more similar to one another than to the members of our own group (the ingroup) We might think they all look alike, think alike, act alike Example: Women perceived more similarly between members in other sororities than within their own (Park & Rothbart, 1982) Ingroup favoritism = we tend to see our own group as better on any number of dimensions and to allocate more rewards to our own group Example (Tajfel, 1981): Randomly assigned students to Group X or Group Y Subjects are strangers; they never interact with each other; and their actions are anonymous Results: Subjects behave as if those who share their meaningless group label (X or Y) are their good friends or close kin Subjects report liking those who share their label, rating them as likely to have a more pleasant personality and to produce better work than those in the other group Subjects even allocate more money and rewards to those who share their label So even when the groups are completely random, we tend to like our group better than another group Constructive Predictions and Reconstructive Memory 2 thinking processes play an important role in social cognition: Predicting our reactions to future events Remembering past events Both of these are subject to considerable error Research shows that we overestimate the emotional impact of events and the durability of our reactions to these events Example: How good would you feel if you won the lottery, and how long would the good feeling last? How bad would you feel if you got a D on your term paper and how long would the bad feeling last? Winning the lottery would not make you feel as good as you’d predict or for as long as you’d predict, and getting a D would not make you feel as bad as you’d predict or for as long as you’d predict Constructive Predictions and Reconstructive Memory Why do we make these errors in prediction? We fail to recognize our powers of adjustment to happy and sad events When we imagine the future, we focus on only the event in question (e.g., winning the lottery, getting a D) to the exclusion of all other things that will occur at the same time to take the sting out of failure or dilute happiness Constructive Predictions and Reconstructive Memory Like imagining the future, recalling the past plays an important role in our social interactions, and is also subject to bias Remembering is a reconstructive process Our memories are not a literal translation of past events Instead, we recreate our memories from bits and pieces of actual events filtered through and modified by our notions of what might have been, what should have been, and what we would have liked it to have been Our memories are also influenced by what people told us about the specific events Constructive Predictions and Reconstructive Memory Suggestive questioning can influence memory and subsequent eyewitness testimony (Loftus, 1974) Reconstructive memory study (Loftus, 1974) Subjects watched a film depicting a multiple-car accident After the film, subjects were either asked: “About how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” OR “About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?” Subjects who were asked about smashing cars estimated that the cars were going significantly faster A week later, they were also more likely to state (erroneously) that there was broken glass at the scene Autobiographical Memory It’s important to realize that we don’t remember our past as accurately as we would like to believe; revisions and distortions occur over time We have a strong tendency to organize our personal history in terms of self-schemas (Markus, 1977) Self-schemas = coherent memories, feelings, and beliefs about ourselves that hang together and form an integrated whole In other words, we distort our memories in such a way that they fit the general picture we have of ourselves For example, if I believe I had an unhappy childhood, I will have a harder time remembering happy events, and it will be easier to call to mind distressing events Autobiographical Memory Loftus (1993) shows how easy it is to plant false memories of childhood in the minds of young adults merely by instructing a close relative to talk about these events as fact She had an older sibling “remind” a younger sibling about a time they got lost in a mall, and an old man helped them Although this did not actually happen, the majority of participants would claim to remember it happening False memory syndrome = a memory of a past traumatic experience that is objectively false but that people believe occurred Recovered Memory Phenomenon = recollections of a past event (e.g., sexual abuse) that had been forgotten or repressed A great deal of controversy surrounds the accuracy of such memories Research suggests repeated experience of trauma is not typically forgotten Many recovered memories are really unintentionally planted false memories However, it is possible for abuse victims to put the abuse out of their minds and have difficulty remembering it years later Cognitive Conservatism People tend to be conservative: we try to preserve beliefs that are already established in our minds Confirmation bias = when we initially develop an impression, we selectively look for evidence to support our initial beliefs Hindsight bias (the “I-knew-it-all-along” effect) = once we know the outcome of an event, we have a strong tendency to believe that we could have predicted it in advance (this is why some social psychology research seems obvious!) Benefit of cognitive conservatism: it allows us to perceive the social world as coherent and stable Cost of cognitive conservatism: we may distort or miss important information; we could be led to make poor decisions; we may have a mistaken picture of reality Cognitive Conservatism 4 ways to avoid the negative consequences of cognitive conservatism: Be wary of those who try to shape the way you view and define a situation Try to use more than one way to categorize and describe a person or event Try to think of persons and important events as unique When forming an impression, consider the possibility that you might be mistaken How Do Attitudes and Beliefs Guide Behavior? Intuition tells us that attitudes would predict behavior Example: if I like vanilla ice cream, you can predict that I’d choose it over other flavors However, research tells us that this is not always the case Example: even though 90% hotels and restaurants contacted in the 1930s said they would not serve Chinese people (attitude), only 1 refused service when a Chinese couple made an appearance at their establishment (LaPiere, 1934) So our attitudes often are not good predictors of our actual behavior Biases in Social Explanation There are 3 general cognitive biases that affect how we understand social situations: Fundamental attribution error Actor-observer bias Self-biases Biases in Social Explanation Fundamental attribution error = we tend to attribute events mostly to a person’s personality or disposition and underestimate how much the situation/environmental factors influenced their behavior We lose sight of the fact that each individual plays many different social roles and that all of our behavior can be strongly influenced by various situations Examples: If you walk into an unlocked public bathroom and find someone in there, you might think “idiot!” rather than “maybe the lock is broken” Quiz show study (Ross et al., 1977) Participants were randomly assigned to be a questioner, contestant, or spectators The questioner wrote challenging questions; contests answered 40% correctly Results: spectators rated the questioner as above average in general knowledge and the contestants as below average; contestants rated themselves as inferior Everyone fell into the trap of attributing what they saw to personal dispositions and lost sight of the fact that the roles had been randomly assigned Biases in Social Explanation Actor-observer bias = the tendency for individuals to believe that their own actions are caused mostly by situational factors, whereas we tend to believe that others behave in certain ways due to their stable personality characteristics Examples: “I failed the test because of stresses in my life. However, my friend failed the test because she’s not very bright.” Jones (1971): College students are likely to explain the poor performance of others on an IQ test in terms of their ability (dispositional) They’ll explain their own poor performance in terms of the difficulty of the test (situational) Saulpier & Perlman (1981): Prison counselors gave enduring personal characteristics as the reason the inmates were in prison (dispositional) Inmates cited transient situational factors as the reasons for their imprisonment (situational) Biases in Social Explanation Self-biases = attitudes and biases that preserve and enhance our view of ourself Egocentric thought = the tendency to perceive yourself as more central to events than you actually are Examples: A teenager may dread going to school with a pimple on his forehead because “everyone will notice;” however, such worries are often exaggerated College students who wore attention-arousing shirts in front of a room of students thought 50% of the people in the room noticed; in reality, only 20% had noticed (Gilovich et al., 2000) Self-serving bias = a tendency for individuals to attribute their success to stable, personal qualities and attribute their failures to the situation Examples: In a basketball game, if I make a difficult shot, I’ll attribute it to my great talent; if I miss the shot, I might attribute it to how hard the shot was or that someone fouled me Gamblers attribute their successes to great skill and their failures as a fluke Self-serving biases help preserve our self-concept and self-esteem Biases in Social Explanation Benefits of self-biases: If an individual believes he is the cause of good things, he will try harder and persist longer to achieve difficult goals Believing that a defeat is due to bad luck and can be overcome by effort and ability leads to more achievement, better health, and an improved mental outlook (Seligman, 1991) Costs of self-biases: A distorted picture of the self and the world in general The need to serve the self often leads directly and indirectly to negative consequences However, overall, people who are more optimistic tend to be less depressed, even though they are not always the most realistic!