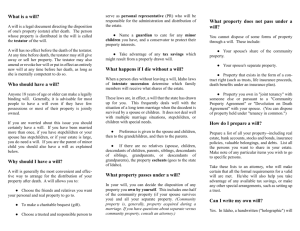

Intestate Succession

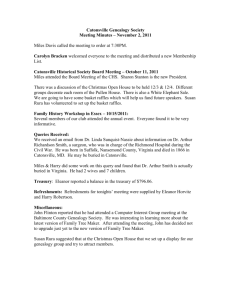

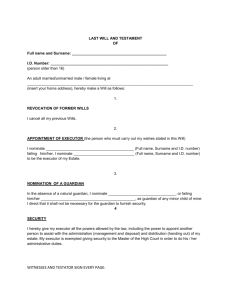

advertisement