4. Hitchcock and Knobe's Theory

advertisement

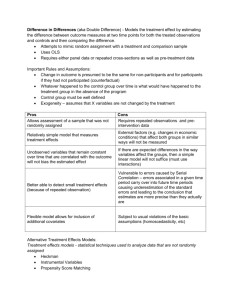

The Role of Counterfactual Reasoning in Causal Judgements peter.menzies@mq.edu.au 1 1. Introduction What is the connexion between counterfactuals and actual/token causation? One idea that has been much explored in philosophy and psychology is that the causal judgement “c caused e” is analytically tied to the counterfactual “If c hadn’t occurred, e wouldn’t have occurred”. The consensus among philosophers is that the concept of actual causation can’t be reduced to counterfactuals. Pre-emption examples pose an insuperable obstacle to such a reduction. 2 1. Introduction The consensus view among psychologists seems to be that counterfactual reasoning and causal reasoning are distinct forms of reasoning. Mandel and Lehman (1996), Mandel (2003), and Byrne (2005) cite experimental data that show that people’s causal judgements of the form “c caused e” are dissociated from counterfactual judgements of the form “If c hadn’t occurred, e wouldn’t have occurred”. The former seem to go with judgements about sufficient conditions and productive mechanisms, whereas the latter seem to go with judgements about enabling conditions and preventative mechanisms. 3 1. Introduction My aim is to argue that philosophers and psychologists have been premature in dismissing the possibility that our causal judgements are analytically connected to counterfactual concepts. But we have to adopt a more subtle view of the connexion in order to able to accommodate the many examples cited as problematic for counterfactual theories. 4 1. Introduction My plan of action: • Outline David Lewis’s counterfactual theory. Explain some problems facing this theory, concentrating on the distinction between enabling conditions and causes, and the distinction between positive and negative causes. • Examine two attempts to rescue the counterfactual theory from these problems – a theory of Chris Hitchcock and Joshua Knobe – a theory of James Woodward • Outline a new theory I think is superior to both these theories. 5 2. Lewis’s Counterfactual Theory Lewis claims that causation can be analyzed in terms of counterfactual dependence defined as: e counterfactually depends on c iff (i) if c were to occur, e would occur; and (ii) if c weren’t to occur, e wouldn’t occur. Counterfactuals are understood in terms of similarity relations between possible worlds. He imposes a constraint on the similarity relation which ensures that a counterfactual with a true antecedent and consquent is itself automatically true. 6 2. Lewis’s Counterfactual Theory This constraint means that his counterfactual dependence can be simplifed to: An occurrent event e counterfactually depends on occurrent event c iff if c weren’t to occur, e wouldn’t occur. Lewis’s definitions of causal concepts: c is a cause of e iff (i) c and e are wholly distinct events; and (ii) there is a chain of counterfactual dependences from c to e. It follows that from this definition that: If e counterfactually depends on a distinct event c, then c causes e. 7 3. Problems for Lewis’s Theory The theory glosses over the distinction between causes and enabling conditions. Example 1: Birth and Death. A man is born and much later dies in a car accident. If he hadn’t been involved in the car accident, he wouldn’t have died. So the car accident counts as a cause of his death. But if he hadn’t been born, he wouldn’t have died. So his birth counts as a cause too. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that the theory is supposed to cover omission and absences. Example 2: The Absence of Meteor Strike. I’m writing this paper at my computer. If I had been struck by a meteor shower, I would not be writing this essay. So the failure of a meteor strike counts as a cause of my writing this essay. 8 3. Problems for Lewis’s Theory The theory has trouble distinguishing between genuine and spurious causes among omissions. Example 3: The Gardener and the Plant A gardener whose job it is to water a plant during hot weather fails to do so and the plant dies. If the gardener had watered the plant, it would have survived. So his failure counts as a cause of the plant’s death. But if the Queen had watered the plant, it would have survived as well. So the Queen’s failure counts as a cause too. 9 3. Problems for Lewis’s Theory Carolina Sartorio (2009) has noted the theory faces the Prince of Wales problem: the problem of unwanted positive causes. Example 4: The Prince and the Plant’s Death The Queen has asked the Prince to water her pot plant in the afternoon. But his priorities are to eat oaten biscuits instead of watering the plant and so the plant dies. The Prince’s failure to water the plants caused the plant’s death. If we add the assumption that if the Prince had not eaten the oaten biscuits, he would have watered the plant, it turns out his eating oaten biscuits counts as a cause of the plant’s death. 10 3. Problems for Lewis’s Theory The problem of unwanted negative causes. Example 5: The Prince and the Stomach Ache The Prince eats oaten biscuits instead of watering the plant. He eats so many biscuits he gets a stomach ache. The Prince’s eating too many oaten biscuits was a cause of his stomach ache. But so too is his failure to water the plant: if he had watered the plant instead of eating the biscuits, he would not have had the stomach ache. Indeed, any action precluded by the Prince’s eating the oaten biscuits (ie talking to the Duke, walking in the garden) will have a corresponding omission that counts as a cause. 11 4. Hitchcock and Knobe’s Theory These problems indicate that a counterfactual of the form “If c weren’t to occur, e wouldn’t occur” is not a sufficient condition for “c is a cause of e”. Lewis defended his theory against such counterexamples by appealing to Grice’s pragmatic theory of conversational implicature. It is literally true that any event or absence on which an effect causally depends is a cause of the effect. “There are ever so many reasons why it might be inappropriate to say something true. It might be irrelevant to the conversation, it might convey a false hint, it might be known to all concerned…” 12 4. Hitchcock and Knobe’s Theory Grice’s maxims are general principles of rationality applied to information exchange. Yet the principles that lie behind our judgements about the examples above seem to be particular to causal judgements. Is it possible to formulate a theory that captures the causation-specific principles that lie behind our judgements? Hitchcock and Knobe (2009) have formulated one such pragmatic theory that preserves the centrality of counterfactual dependence to the causal concept while explaining the selectivity of the causal concept. 13 4. Hitchcock and Knobe’s Theory Their theory appeals to findings in the literature on psychological availability of counterfactual suppositions. One of the most robust findings in this literature is that people are disposed to entertain counterfactual hypotheses that undo the past by changing abnormal occurrences into normal ones, but seldom, if ever, do they mentally undo the past by changing normal occurrences into abnormal ones. Kahneman and Tversky (1982) gave subjects a story describing a fatal road accident in which a truck ran a red light and crashed into a passing car, killing its occupant, Mr Jones. 14 4. Hitchcock and Knobe’s Theory Two versions of the story were constructed: one in which Mr Jones left his home at the regular time but took an unusual route home, and the other in which he took the usual route home but left early to do some chores. In 80% of the responses, subjects indicated they mentally undid the accident by mutating the abnormal event and restoring it back to normality. In the first version of the story, subjects were inclined to entertain counterfactuals about what would have happened if Mr Jones had taken his usual route home. In the second version they were more inclined to entertain counterfactuals about what would have happened if Mr Jones had left work at his usual time. 15 4. Hitchcock and Knobe’s Theory Hitchcock and Knobe use this finding to explain the selectivity of the causal concept. We readily accept a causal judgement “c caused e” when the counterfactual “If c hadn’t occurred, e would have occurred” involves changing an abnormal occurrence into a normal one; we rarely accept such a causal judgement when the counterfactual involves changing a normal occurrence into an abnormal one. They claim that we classify events in terms of single scale of normality that takes into account both statistical and prescriptive considerations. 16 4. Hitchcock and Knobe’s Theory They presented subjects with a vignette in which a receptionist in the philosophy department keeps her desk stocked with pens. In contrast to administrative assistants who are permitted to take pens, faculty members are supposed to buy their own. One day an administrative assistant and Professor Smith walk past the receptionist’s desk and both take pens. Later that day, the receptionist needs to take a message but can’t do so because there are no pens on her desk. When subjects are asked whether the administrative assistant or Professor Smith caused the problem, most subjects say that Professor Smith was the cause. Hitchcock and Knobe’s explanation: “If Professor Smith had not taken a pen, there would have been no problem” involves a norm-restoring antecedent and so the corresponding causal judgement is acceptable. “If the administrative assistant had not taken a pen, there would have been no problem” involves replacing a normal occurrence with an abnormal or neutral occurrence and so the corresponding causal judgement is not acceptable. 17 4. Hitchcock and Knobe’s Theory How does their theory fare in dealing with Problems 1 to 5? Problem 2: The Absence of Meteor “The absence of the meteor strike caused me to write this paper” is not acceptable because the corresponding counterfactual involves changing a normal event into an abnormal event. Problem 3: The Gardener and the Plant “The gardener’s failure to water the plants caused the pant to die” is acceptable because the corresponding counterfactual involves a norm-restoring change. “The Queen’s failure to water the plants caused the plant to die” is not acceptable because the corresponding counterfactual doesn’t involve a norm-restoring change. Problem 4: Prince of Wales: Unwanted Positive Causes “The Prince’s failure to water the plant caused its death” is acceptable for the same reasons as above. “The Prince’s eating oaten biscuits caused the plant’s death” is unacceptable for the same reasons as above. 18 4. Hitchcock and Knobe’s Theory Note that in all the examples, the counterfactuals corresponding to both causes and non-causes are true. In the Problem 3 The Gardener and the Plant, it is true both: If the gardener had watered the plant, it would not have died. If the Queen had watered the plant, it would not have died. Hitchcock and Knobe say that the first counterfactual is more “relevant” than the second. But what is relevance? Relevant = spring to mind readily. We need an account of the difference in causal status that’s independent of whether something springs to mind readily. Relevant = acceptable when explicitly entertained. Both counterfactuals seem to be acceptable. Relevant = worth entertaining for practical purposes. From our perspective, neither counterfactual is practically significant. 19 4. Hitchcock and Knobe’s Theory Another problem concerns the psychological findings that demonstrate a dissociation between causal judgements and reasoning about counterfactuals. Mandel (2003) made a study using the example of Mr Jones and the drunk driver. When asked for their counterfactual judgements, many subjects responded with judgements “If Mr Jones hadn’t taken the unusual route (or left at the unusual time), he would not have died”. When asked for their causal judgements, most respond with the judgement “The drunk driver caused Mr Jones’s death”. Such studies cast doubt on the claim that the acceptability of the causal judgement “c caused e” goes hand-in-hand with the acceptability of “If c hadn’t occurred,e wouldn’t have occurred.” 20 5. Woodward’s Theory Like Hitchcock and Knobe’s theory, Woodward’s theory attempts to explain the selectivity of causal judgements by augmenting Lewis’s counterfactual theory with additional constraints. Like Lewis, he defines counterfactual dependence between states (including events, absences and omissions) in terms of these counterfactuals: (i) If c were to occur, e would occur [occurrence counterfactual] (ii) If c weren’t to occur, e wouldn’t occur [non-occurrence counterfactual] 21 5. Woodward’s Theory Woodward says that for the causal judgement “c caused e” to be acceptable, the occurrence-counterfactual (i) must be insensitive: ie. there is a broad range of background conditions Bi that are not “too improbable or far-fetched” such that the following counterfactual is true: If c were to occur in circumstances Bi different from the actual circumstances, then e would occur. Example of insensitive causation: Shooting a person at close range with a large calibre bullet caused his death. Example of sensitive causation: Lewis’s writing a letter of recommendation for jobseeker X caused the death of a descendant of another jobseeker Y who was displaced by X. 22 5. Woodward’s Theory Woodward’s theory links our readiness to accept a causal judgement to the degree of insensitivity of the occurrencecounterfactual (i). It explains some of our causal judgements about the earlier examples. Problem 2: The Absence of the Meteor Strike “The absence of the meteor strike caused me to write this paper” is not acceptable because the corresponding occurrence-counterfactual “If there were no meteor, I would write this paper” is not insensitive. Note that if I had been struck by a meteor, then the occurrence-counterfactual would be “If there were a meteor strike, I would not write this paper”, which is insensitive. 23 5. Woodward’s Theory However, Woodward’s theory doesn’t deal satisfactorily with example of Mr Jones and the Drunk Driver: “Mr Jones’ taking an unusual route home caused his death” has a sensitive occurrence-counterfactual: an admissible variation is one in which drunk driver doesn’t run the red light. “The drunk driver’s running the red light caused Mr Jones’s death” also has a sensitive occurrence-counterfactual: an admissible variation is one in which Mr Jones doesn’t take the unusual route home. Accordingly, we should say that neither Mr Jones’s taking the unusual route home nor the drunk driver’s running the red light caused Mr Jones’ death. 24 5. Woodward’s Theory Woodward’s theory doesn’t handle one half of the Prince of Wales problem: problem of unwanted positive causes. “The Prince’s failure to water the plant caused its death” has an insensitive occurrence-counterfactual. So the Prince’s failure to water the plant counts as a cause of the plant’s death. But “Prince’s eating oaten biscuits caused plant’s death” also has an insensitive occurrence-counterfactual: any variation on the actual circumstances which respects the stipulation that the Prince’s eating oaten biscuits precludes him from watering the plant will make the occurrence-counterfactual true. 25 5. Woodward’s Theory It’s not clear that the theory has a satisfactory explanation of the problem of the professor and the administrative assistant. Is the occurrence-counterfactual “If the professor were to take a pen, there would be a problem” insensitive? There seem to be admissible variations in which the professor takes a pen but the administrative assistant does not, in which case there would be no problem. 26 6. A New Theory Hitchcock and Knobe’s theory seems to be closer to the truth than Woodward’s. I offer a theory that builds on and improves on the Hitchcock and Knobe theory. (a) Semantic rather than pragmatic theory. Hitchcock and Knobe’s theory is a pragmatic theory of relevance added onto a standard semantics of counterfactuals. I believe it is more fruitful to see our causal judgements about the various examples as reflecting their actual meaning. The theory I’m presenting states that the meaning of a causal judgement involves a contrast between the actual course of events and a counterfactual course of events. 27 6. A New Theory In this pair of contrasting situations, the actual situation contains an abnormal sequence of events which invites explanation or the ascription of responsibility. Counterfactual situation= default course of events Actual situation= deviant course of events The actual situation deviates from the default situation by virtue of containing abnormal sequence of events. The paradigm case is a sequence of events initiated by an intentional action that is an exogenous interference in the normal course of events. 28 6. A New Theory (b) Salience of counterfactual possibilities rather relevance of counterfactuals The theory says that in considering a causal judgement we tacitly treat certain counterfactual possibilities as salient. We select a counterfactual possibility as a default to the actual situation in which a state c obtains in such a manner that it meets the following condition: the counterfactual possibility must be a norm-conforming situation in which c does not obtain. As in Hitchcock and Knobe’s theory, the norms include statistical norms, social and ethical norms, and norms of proper functioning. I also assume that in a given context we judge situations to be more or less normal in terms of single scale. 29 6. A New Theory While this theory appeals to counterfactual possibilities, it avoids the use of counterfactuals. As we saw earlier, in most of the examples, both the causes and non-causes have true non-occurrence counterfactuals. Eg If the gardener had watered the plant, it would not have died. If the Queen had watered the plant, it would not have died. Hitchcock and Knobe’s theory then has to invoke the notion of “relevance” to sort out the causes from the non-causes. It is best simply to miss out the distracting detour through counterfactuals. 30 6. A New Theory (c) Causation as difference-making without counterfactuals. Hitchcock and Knobe’s theory appeals to nonoccurrence counterfactuals to spell out the idea that causation is linked to difference-making. The present theory spells out this idea out more directly: “c is a (difference-making) cause e” is true iff there is a contrast pair <A,C>, where A is the actual situation and C is an appropriate default counterfactual situation such that c and e are present in A but absent in C. 31 6. A New Theory (d) Better explanation of causal judgements. The theory explains our causal judgements about the examples roughly in the same way as Hitchcock and Knobe’s theory. The Absence of the Meteor Strike: “The absence of a meteor strike was a cause of my writing this paper” is false because there is no contrast pair with an appropriate default counterfactual situation (any situation in which I am struck by a meteor is abnormal) Prince of Wales: Unwanted Positive Causes “The Prince’s failure to water the plant was a cause of its death” is true because there is contrast pair with a default counterfactual situation (where the Prince meets his obligation) which meets the difference-making condition. “The Prince’s eating oaten biscuits was a cause of the plant’s death” is false because there is a contrast pair with a salient default counterfactual situation (where he meets his obligation) but it doesn’t meet the difference-making condition. 32 6. A New Theory The present theory is consistent with the psychological studies showing that causal judgements are dissociated from judgements about counterfactuals. The present theory employs counterfactual possibilities but not counterfactuals. Nonetheless, it strikes me that Mandel’s use of the example about Mr Jones and drunk driver doesn’t bear out this dissociation very well. In this example, Mr Jones’s taking an unusual route and the drunk driver’s running the red light were causes of his death. In each case there is an appropriate contrast pair meeting the difference-making condition. 33 6. A New Theory (e) Better Rationale for Causal Concept Why do we have the concept of actual causation (in addition to the concept of objective causal structure)? Hitchcock and Knobe claim that its purpose lies in its connexion with norms: through its connexion with non-occurrence counterfactuals, the concept enables us to focus on what must be done to bring events into conformity with certain norms. “In short, the concept of actual causation enables us to pick out appropriate targets for intervention.” In contrast, the concept of actual causation has a very easy-to-understand rationale according to the present theory. The concept has its home in our practices of explanation and the attribution of responsibility. When an occurrence violates a statistical norm, we want to have an explanation of it. When it violates a prescription norm, we want to attribute responsibility for it to someone. A cause that makes a difference is perfectly suited to meet these functions. 34