L&K Chaperone Policy - Lepton & Kirkheaton Surgeries

advertisement

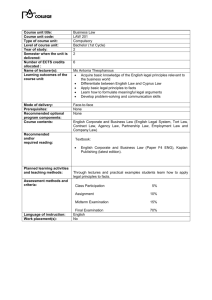

Lepton & Kirkheaton Surgeries Chaperone Policy and Practice Training Programme For Staff CONTENTS Chaperone Policy for our Patients- published on our website and available in our waiting rooms. Guidance from the General Medical Council regarding Intimate examinations and chaperones-April 2013 Overview fact sheet from The Medical Protection Society about Chaperones-July 2014 Key points to remember regarding Chaperoning Chaperoning- practical aspects for our Staff Why bother and why now? The Ayling Report When to use chaperones Which examinations? What to do when patients decline a chaperone Home visits Who should chaperone? Communication Requirements for intimate examinations Training for chaperones o What is your role? o What should you expect to happen? o When should you leave? o What type of examinations may you be asked to witness and what happens in each? o Breast examination o Female Pelvic/Vaginal examination o Rectal examination o Male genital examination Chaperone Poster for waiting rooms and above couches References Page number 2 5 6 8 9 11 11 12 13 13 14 15 16 17 17 17 18 18 19 21 27 28 29 30 This policy should be read in conjunction with viewing the DVD on Chaperones as issued by the GHCCG in August 2014. Created by Dr Saheli Chaudhury-August 2014 1 Chaperone Policy for our Patients You can also find this information on our website www.lepton-kirkheatonsurgeries.nhs.uk What to expect: Lepton and Kirkheaton Surgeries as a Practice are committed to providing a safe and comfortable environment where patients and staff can be confident that “Best Practice” guidance as recommended by The General Medical Council of the United Kingdom is being followed at all times. We recognise that we have an obligation to respect the dignity of each patient and to conduct each consultation in a manner that strives to provide a comfortable, confidential, private and safe environment. What is a Formal Chaperone? Witness Support Safeguard In clinical medicine, a formal chaperone is a person who acts as a: Witness for both a patient and a clinician/health care professional usually a doctor or nurse. Support providing comfort and reassurance to the patient and verifies continued consent to the examination or medical procedure. Safeguard for both parties during a medical examination or procedure and is a witness to continuing consent of the procedure which is turn safeguards the Practice against formal complaints or legal action. A friend or relative of the patient is NOT an impartial observer, and so CANNOT act as a formal chaperone but should be allowed to stay if the patient so wishes. 2 Why do we need Chaperones? There are two main considerations involved in having a chaperone to assist during intimate examinations; 1. To offer support and comfort to the patient 2. The protection of the doctor or nurse from allegations of impropriety. The following groups or situations are when the need for a chaperone can commonly arise: Vulnerable adults Anyone requiring an intimate examination Under 16s attending alone ‘At risk’ patients Unknown patients new to the list Examination at close proximity What is an intimate examination? Usually considered to be an examination of any part of the body between the collar bones and the knee. Obvious examples of an intimate examination include examinations of the breasts, genitalia and the rectum. However, some patients may be uncomfortable with examinations at close proximity for example conducting eye examinations in dimmed lighting. Parents can give consent for the new born or six week baby check where the baby has to be fully undressed. The rights of the Patient: All patients are entitled to have a chaperone present for any consultation, examination or procedure where they feel one is required. Patients have the right to decline the offer of a chaperone. However the clinician may feel that it would be wise to have a chaperone present for their mutual protection for example, an intimate examination on a young adult of the opposite gender. If the patient still declines the doctor will need to decide whether or not they are happy to proceed in the absence of a chaperone. This will be a decision based on both clinical need and the requirement for protection against any potential allegations of improper conduct. 3 Appropriately Trained Chaperone: Appropriately trained Chaperone is defined as a member of our Practice staff who has completed the Practice Training Programme. If an intimate examination is required, the clinician will: Establish there is a need for an intimate examination and discuss this with the patient. Give the patient the opportunity to ask questions. Obtain and record the patient’s consent. Offer a chaperone to all patients for intimate examinations (or examinations which may be construed as such). If the patient does not want a chaperone it will be recorded in the notes. The Patient can expect the chaperone to be: Available if requested. Pleasant, approachable, professional in manner and to be able to put them at ease. Clean and presentable. Confidential. Where will the chaperone stand? What will they do? The positioning of the chaperone will depend on several factors for example the nature of the examination and whether or not the chaperone has to help the clinician with the procedure. The clinician will explain to you what the chaperone will be doing and where they shall be in the room. During the time that a chaperone is present, the doctor or nurse will strive to keep all enquiries of a sensitive nature to a minimum. The clinician will document and record the name of the chaperone in your medical notes. When a chaperone is not available: There may be occasions when a chaperone is unavailable, for example on a home visit, then in such circumstances the doctor will assess the circumstances and decide if it is appropriate to go ahead without one or rearrange another date for examination with a chaperone present. Should you have a concern about a chaperone: Patients should please raise any concerns about a chaperone to a GP Partner or the Practice Manager. If you wish to make a complaint please do so in writing via the Practice’s usual comments/complaints procedure. 4 Guidance from The General Medical Council (GMC) regarding Intimate examinations and Chaperones- April 2013 The GMC brought out new guidance in April 2013 regarding Intimate examinations and chaperones. Chaperones should be familiar with the adapted guidance below: When an intimate examination is to be performed, we should offer the patient the option of having an impartial observer (a chaperone) present wherever possible. This applies whether or not you are the same gender as the patient. A chaperone should usually be a health professional and but a chaperone should: a) be sensitive and respect the patient’s dignity and confidentiality b) reassure the patient if they show signs of distress or discomfort c) be familiar with the procedures involved in a routine intimate examination d) stay for the whole examination and be able e) to see what the doctor is doing, if practical f) be prepared to raise concerns if they are concerned about the doctor’s behaviour or actions. A relative or friend of the patient is not an impartial observer and so would not usually be a suitable chaperone, but you should comply with a reasonable request to have such a person present as well as a chaperone. If either the doctor or the patient does not want the examination to go ahead without a chaperone present, or if either of them is uncomfortable with the choice of chaperone, you may offer to delay the examination to a later date when a suitable chaperone will be available, as long as the delay would not adversely affect the patient’s health. If the doctor does not want to go ahead without a chaperone present but the patient has said no to having one, the doctor must explain clearly why you want a chaperone present. Ultimately the patient’s clinical needs must take precedence. You may wish to consider referring the patient to a colleague who would be willing to examine them without a chaperone, as long as a delay would not adversely affect the patient’s health. You should record any discussion about chaperones and the outcome in the patient’s medical record. If a chaperone is present, you should record that fact and make a note of their identity. If the patient does not want a chaperone, you should record that the offer was made and declined. 5 Overview factsheet from The Medical Protection Society about Chaperones -July 2014 Regardless of the patient’s role, the guidelines from medical regulatory bodies are clear: it is always the doctor’s responsibility to manage and maintain professional boundaries – utilising chaperones effectively is a way of managing relations with patients, where the ultimate responsibility for ensuring that relations remain on professional footing rests with you. Background In 2004 the Committee of Inquiry looked at the role and use of chaperones, following its report into the conduct of Dr Clifford Ayling. It made the following recommendations: Each trust should have its own chaperone policy and this should be made available to patients. An identified managerial lead (with appropriate training). Family members or friends should not undertake the chaperoning role. The presence of a chaperone must be the clear expressed choice of the patient; patients also have the right to decline a chaperone. Chaperones should receive training. Why use chaperones? Their presence adds a layer of protection for a doctor; it is very rare for a doctor to receive an allegation of assault if they have a chaperone present. To acknowledge a patient’s vulnerability. Provides emotional comfort and reassurance. Assists in the examination. Assists with undressing patients. Enables them to act as an interpreter. What is an intimate examination? Obvious examples include examinations of the breasts, genitalia and the rectum, but it also extends to any examination where it is necessary to touch or be close to the patient; for example, conducting eye examinations in dimmed lighting, taking the blood pressure cuff, palpitating the apex beat. Consult GMC and NMC advice on intimate examinations (see further information). How to develop a chaperone policy Here is a useful checklist for the management of a consultation: Establish there is a need for an intimate examination and discuss this with the patient. 6 Explain why an examination is necessary and give the opportunity to ask questions; obtain and record the patient’s consent. Offer a chaperone to all patients for intimate examinations (or examinations that may be construed as such). If the patient does not want a chaperone, record this in the notes. If the patient declines a chaperone and as a doctor you would prefer to have one, explain to the patient that you would prefer to have a chaperone present and, with the patient’s agreement, arrange for a chaperone. If the patient continues to decline a chaperone, consider transferring their care to an available colleague who would be willing to examine them without a chaperone. Ultimately, the patient's clinical needs must take precedence, and such arrangements must not cause a delay that would adversely affect the patient's health. Be aware and respect cultural differences. Religious beliefs may also have a bearing on the patient’s decision over whether to have a chaperone present. Give the patient privacy to undress and dress. Use paper drapes where possible to maintain dignity. Explain what you are doing at each stage of the examination, the outcome when it is complete and what you propose to do next. Keep the discussion relevant and avoid personal comments. Record the identity of the chaperone in the patient’s notes. Record any other relevant issues or concerns immediately after the consultation. In addition, keep the presence of the chaperone to the minimum necessary period. There is no need for them to be present for any subsequent discussion of the patient’s condition or treatment. Written information detailing the policy should be provided for patients, either on the practice website or in the form of a leaflet. Where should the chaperone stand? Exactly where the chaperone stands is not of major importance, as long as they are able to properly observe the procedure so as to be a reliable witness about what happened. 7 Key points to remember regarding Chaperoning: Inform your patients of the practice’s chaperone policy. Record and document clearly the use, offer and declining of a chaperone in the patient’s notes. Ensure training for all chaperones. Be sensitive to a patient’s ethnic/religious and cultural background. The patient may have a cultural dislike to being touched by a man or undressing. Do not proceed with an examination if you feel the patient has not understood due to a language barrier 8 Chaperoning- Practical Aspects for our Staff A chaperone should: 1. Make themselves available as soon as practicable to assist in an examination or make clear to the doctor when they expect to be available. This is to avoid any undue delay while the patient may be partially undressed which may increase patient’s anxiety which may already be heightened before an intimate examination. . If you recognise the identity of the patient, inform the doctor who may offer the patient the option of another chaperone or postponing the examination to another time. 2. You should allow the patient sufficient time and privacy to undress. Assist if absolutely necessary. Please ensure the patient has been given a “MODESTY SHEET”. 3. Ask the patient’s permission to enter inside the curtain and be sensitive in protecting their dignity prior to the examination. The doctor themselves may ask their permission to enter first and then you may both enter together. 4. Introduce yourself to the patient, by name and inform them of your role. 5. You should verify the patient’s understanding of the type of examination i.e. breast, anal, vaginal or breast. This is to open channels of communication between the chaperone and patient to enable the chaperone to provide emotional comfort and reassurance. It may be difficult for a patient to convey doubt or distress to a chaperone if the chaperone appears silent and unapproachable. 6. It is important to minimise personal discussions with the patient during the examination and if possible avoid commenting on confidential medical or social issues during this time. However, if you feel the patient requires information in order to proceed with the examination either alert the doctor or offer an explanation to the patient. 7. Assist the doctor in positioning the patient if required and stand where appropriate for the necessary examination often 9 at the head end of the bed to observe for any signs of distress or discomfort of the patient. 8. If any undue discomfort is noticed, it is important to recognise that the doctor may not be aware of this while he or she is focussed on other aspects of the examination. The chaperone should therefore ask the patient, ‘Is that uncomfortable for you? ‘to alert the doctor to any distress and allow the patient to communicate this. Provide reassurance if the patient wishes to continue. If there is any doubt as to whether the doctor has appreciated your concern, then please be more explicit if required. 9. If undue discomfort or distress occurs at this time or any other, the patient should be asked, ‘Do you want the doctor to go no further?’ The patient’s request to stop should always be respected. 10.Please consider patient confidentiality during discussions between the doctor and patient regarding medical conditions which should preferably be delayed until after the chaperone has departed. 11.If you have concerns following an examination, please contact the practice manager as soon as possible following the examination or if you require clarification over a certain aspect of the examination, please ask the doctor concerned in a private and confidential manner. 12.Rarely, a patient may insist that a chaperone is not present during an intimate examination. On these occasions it may be necessary for a doctor to ask an impartial witness such as a receptionist or nurse, to verify that the patient insists that a chaperone is not present even though it has been suggested by the doctor. Even in these circumstances, if a doctor does not wish to go ahead with an examination, then he or she is not obliged to e.g. with a patient who may not be competent to consent to an intimate examination or if a suspicion of undue coercion exists. 10 CHAPERONES: Why bother, and why now? For any health professional an accusation of inappropriate behaviour towards a patient is devastating and the consequences can be far reaching. Cases can take many months, and often years, to resolve, by which time the doctor concerned may have been through criminal, civil, and regulatory authority proceedings as well as facing adverse publicity in the media. The presence of a chaperone can often protect both the doctor and the patient from potential allegations. The Ayling report, published in September 2004, after Clifford Ayling, a general practitioner from Folkestone, Kent was convicted of 13 counts of indecent assault on female patients, was the result of an independent inquiry into the way that the NHS dealt with allegations about the conduct of Clifford Ayling and it highlighted the issue of chaperones. The report found a lack of common understanding of the purpose and use of chaperones across the NHS. It found that chaperones were used in various settings and circumstances with differing levels of risk to patients and healthcare professionals It recommended that: o Trained chaperones should be available to all patients having intimate examinations. Untrained administrative staff or family or friends of the patient should not be expected to act as chaperones o The presence of a chaperone must be the patient's choice and they must be able to decline a chaperone if they wish o All NHS trusts need to set out a clear chaperone policy and should ensure that patients are aware of it and that it is adequately funded. The report recognised that for primary care a policy will have to take into account issues such as one to one consultations in patients' homes and the capacity of practices to meet the requirements of an agreed policy When to use chaperones Chaperones: Safeguard the patient against abuse during examination. Great emphasis is given to the role of the chaperone in protecting the patient against sexual abuse though this is probably very rare. Can protect the patient against other forms of real or perceived abuse. The presence of a chaperone acts as a safeguard against a 11 doctor causing unnecessary discomfort, pain, humiliation or intimidation during examination. May provide reassurance to an anxious patient. Can inform the doctor of the patient’s discomfort, if on occasions when the doctor’s attention is focused on performing the examination. The chaperone can maintain communication and eye contact with the patient. May assist an infirm or disabled patient with dressing and undressing. Protects doctors against false allegations of sexual abuse. There are theoretical disadvantages of a chaperone being present during a gynaecological examination. Gynaecological consultations occasionally provide an opportunity for women to confide deeply sensitive information about sexual abuse, previous termination of pregnancy or domestic violence. The presence of a chaperone may intrude in a confiding doctor–patient relationship and may lower a doctor’s alertness to detecting non-verbal signs of distress from the patient. This drawback is potentially offset by confining the presence of chaperones to the physical examination and allowing one-to-one communication for the consultation. Clearly levels of embarrassment may increase in proportion to the number of individuals present during an examination. Which Examinations? The General Medical Council and the Medical Protection Society advise that when doctors have to carry out intimate examinations— those of the breast, genitalia, or rectum—they should always offer a chaperone. If there are not enough staff to provide one you should not proceed if you have concerns. Postponing an examination because there is no chaperone is acceptable unless it is an emergency. Chaperones are advised whether the patient is the same sex and the clinician or not. A a female GP received a complaint from a female patient, though it was withdrawn some months later. It is not just intimate examinations that cause problems, and you should trust your instincts before performing any examination. If you are worried or the patient seems unduly reluctant to be examined, arrange for a chaperone or refer the patient to a colleague. A patient's cultural and religious beliefs should also be taken into account when considering a chaperone 12 Adolescent patients generally have a lower embarrassment threshold and so a chaperone may be used in situations where you would not usually use one. Many patients feel that the presence of a third party during an intimate examination is intrusive and embarrassing. Patients have the right to decline a chaperone and you should not make them feel obliged to accept one. If a chaperone is offered and declined, make a note of this is in the patient's records with any relevant discussion. One American healthcare provider http://www.healthcaresouth.com/pages/chaperone.htm publishes its chaperone policy and attempts to reduce patient concern with the statement ‘the health care provider will strive to keep all inquiries of a sensitive nature to a minimum’ [when the chaperone is present]. When a chaperone is used it should be recorded in the notes their name and position. If a complaint is made at a later date it is unlikely that you will remember who was present at the examination. What do when patients decline a chaperone? The Ayling report recognised a patient's right to decline a chaperone. It also acknowledged that a chaperone may not always be available. As a result there are no cast iron rules governing their use, and it is often a question of using your professional judgment to assess an individual situation. Record in the notes that you have offered a chaperone and it has been declined However, you also have the right to protect yourself, and if you do not want to proceed with an examination without a chaperone explain this and ask the patient to change his or her mind or accept referral to another doctor. Many patients feel that a request for a chaperone is a reflection on them and that you think they are not trustworthy. If you decline to perform an examination because there is no chaperone you should explain that it is for practical reasons. Home visits If an intimate examination is required in a patient who cannot attend the surgery, unless the examination is needed urgently, it should be postponed until a chaperone is available. This should be explained to the patient and only if the patient declines the presence of a chaperone and the clinician is comfortable to proceed should they do s Who should chaperone? 13 While some patients may welcome the presence of a family member acting as chaperone, there are potential disadvantages. The presence of a family member may reduce the likelihood of disclosure of sensitive information and delay the development of self-confidence in young women. The presence of a dominant male partner may inhibit communication about past gynaecological or obstetric history, marital or sexual problems or domestic violence. Some male partners may consider a clinician’s examination as unacceptable particularly any discomfort caused and may then intervene inappropriately. An accompanying female relative may bring to the consultation her own agenda of prejudices and fears about gynaecological examinations. It is the view of the Medical Protection Society that a family member would not fulfil their criteria for a chaperone, which they define as ‘someone with nothing to gain by misrepresenting the facts’. After careful consideration, the Working Party on Intimate Examinations of the Royal College of Gynaecologist recommends that a chaperone should be available to assist with gynaecological examinations irrespective of the gender of the gynaecologist. Ideally, this assistant should be a professional individual. Ideally, chaperones should be another member of the clinical team, but this is not always possible. The Ayling report states that chaperones do not have to be health professionals but they do need to have some training. The report also says that family members or friends of the patients "should not be expected to undertake any formal chaperoning role." There is a risk of inadvertent breaches of confidentiality and embarrassment if friends or relatives are chaperones, and they are best avoided unless there is no alternative and postponing the examination is not possible. If the chaperone is not someone the patient knows, it is helpful to introduce them and explain their role. Document chaperone’s name in the notes The Medical Protection Society dealt with a case where a GP was accused of making inappropriate comments while examining a young female patient. The complaint was made months after the examination and the doctor could not remember who had acted as chaperone, although he was sure that he would not have conducted an intimate examination without one as the practice had a strict policy on chaperone use. Unfortunately, he had not made a note of the chaperone's name or position and the complaint was upheld. 14 When a chaperone is in the room you should be cautious about what you say. It is easy to breach confidentiality unwittingly. The chaperone should be present only for the physical examination, and you should wait until he or she has left before discussing any aspect of the patient's care. Regardless of whether a chaperone is present, it is wise to be careful about making personal comments while examining a patient. A person who is feeling embarrassed or vulnerable is more likely to misinterpret a comment. Communication Communication failures often lead to complaints, and it is not unusual for the Medical Defence Organisations to be contacted by doctors facing serious allegations because the patient has misunderstood a justifiable clinical examination. A typical example is where a GP saw a teenage girl with suspected glandular fever. Without explaining his actions he moved close and began to feel the lymph glands in her armpits. The patient consequently complained that the GP had fondled her breasts. Another example is where an ophthalmologist needed to perform a fundoscopy. He turned off the light and moved close to the patient without explaining what he was doing. The patient thought he was going to kiss her and complained. Another example, is when a GP examined a patient’s breasts and while inspecting them for differences in contour, colour and shape, the patient thought the doctor was in fact ogling her breasts rather than examining them and subsequently complained. It is vital to be aware of how a patient may perceive a situation. Although it may be a procedure that you carry out regularly, you should ensure that you have done everything to avoid misunderstandings. Explain what the examination entails and give the patient the opportunity to ask questions. It is particularly important to explain your actions if you need to examine one part of the body when the symptoms are felt in another. In both these cases the doctors did not consider using a chaperone as they did not think that there could be a problem. However, because they had not explained what the examination entailed and why it was necessary the patient misconstrued their actions and both doctors had to deal with complaints. 15 There is no absolute guarantee against an allegation of inappropriate behaviour. Misunderstanding and maliciousness will continue to cause problems for doctors across all specialties. However, a chaperone used correctly and sensitively will considerably reduce the chance of facing the nightmare of a complaint. Requirements for intimate examinations Patients should be provided with private, warm and comfortable changing facilities. Provision should be made for clothing to be laid aside appropriately and for the disposal of sanitary towels, tampons or incontinence pads. After undressing there should be no undue delay prior to examination. Some patients will welcome a choice between donning a gown or continuing to wear some of their own clothes, e.g. a wide skirt with underwear removed. Alternatively, they may welcome the opportunity of bringing their own robe. Muslim women will wish to continue to wear their head attire. The woman should be given every opportunity to undress herself with assistance from a nurse, chaperone or relative if this is necessary due to infirmity. No assistance should be given with removing underwear unless absolutely necessary. Every effort must be made to ensure that gynaecological examinations take place in a closed room that cannot be entered while the examination is in progress and that the examination is not interrupted by phone calls or messages about other patients. In addition to the explanation given prior to the examination, it may be helpful to give a running commentary on what is being done during the examination. Terms of endearment such as ‘pet’, ‘love’ or ‘dear’ should be avoided during consultations, especially while performing pelvic examination. It is probably better to avoid the use of first names under these circumstances also. No remarks of a personal nature should be made during the examination, even if they may be clinically relevant. For example, advice about the risks of sunbathing prompted by the presence of a deep suntan should be given after the examination has concluded. Similarly, no comment or discussion about body weight should take place while the woman is undressed, despite its relevance to many health problems. 16 Training for Chaperones What is your role? Intimate examinations are part of the day to day work of all General Practitioners and Nurses who work in primary care. They are an area where misunderstanding can easily arise and cause the patient anxiety or compromise the doctor patient relationship. It is worth noting that the GMC receives a significant number of complaints, each year, from patients concerned about the purpose, nature and conduct of such examinations. A chaperone can fulfil a number of purposes. The most quoted one is protection for the doctor and/or the patient against misunderstanding or against false allegations of misconduct. In addition a chaperone can also be a support to patients in this particularly vulnerable situation. What should you expect to happen? The clinician (and yourself) should be respectful of the individual at all times as the patient will be in a situation where people commonly feel vulnerable. The purpose and nature of the examination should be clearly explained in terms that the patient is likely to understand and permission should have been sought to proceed. This is normally simply a question of ‘Is that ok?’ after an explanation of what’s going to happen. This may have been done whilst the clinician is waiting for you to come in. In the case of children they can choose to be examined without a parent present providing the practitioner feels the child is sufficiently mature to make that decision. Normally we would expect the parents to be present but there may be reasons why the child does not want them present and it’s the doctor or nurses’ decision whether to proceed. Sensitivity to the patient’s situation should be displayed by allowing undressing in private and providing suitable coverings. In some practices this is practically very difficult due to a lack of space for separate examination rooms or even curtains in small consulting rooms. Once undressed patients should be covered using a clean sheet, gown or a sheet of couch roll to do this. The amount of the patient’s body that is exposed should only be that that is necessary to carry out the examination. It is seldom the case that an individual should be completely stripped. 17 Whilst discussion during the examination may be helpful to keep the patient informed and to assist in the process itself the clinicians will try to avoid unnecessary discussion to help protect the patient’s confidentiality. Sometimes the clinician will engage in conversation to help the patient relax but there should be no inappropriate personal comment. The clinician and the chaperone should not engage in any discussion that is not relevant to that patient’s examination. Medical gloves should be worn for certain intimate examinations (e.g. pelvic and rectal examinations). These provide a physical barrier quite separate from fulfilling any hygiene or prevention of infection purpose. Examinations are sometimes uncomfortable for the patient but if you observe discomfort which you feel the clinician is not aware of you should make them aware by asking the patient ‘Is that hurting a lot?’ or ‘Do you want the doctor/nurse to stop?’ You might mention the patient’s discomfort to the clinician afterwards and seeing what their response is eg ‘Mrs Jones seemed to be in a lot of discomfort during the examination’. If the clinician does not behave in an appropriate way to these comments, in your view, you should consider informing your line manager who should mention it to the clinician themselves or to a colleague. Although this may sound like ‘telling tales’ it is only from the observations of chaperones can inappropriate behaviour be tackled. Silent acceptance of potential abuse of patients by clinicians is not acceptable. When should you leave? After the examination the doctor will advise the patient to get dressed. He or she might help the patient to get up and you should help remain in the room until the patient is covered, with their upper and lower garments on. You may be able to make yourself feel less awkward by changing the couch roll or by asking the doctor if you can assist in labelling specimens or completing request forms. Unless the patient is particularly infirm or unsteady you should not help the patient get dressed. If you do assist the patient you should consider do you need to wash your hands afterwards? What type of examinations may you be asked to witness and what happens in each? Breast Female pelvic/vaginal Rectal Male genital 18 Breast examination The following descriptions are from an online resources and textbooks. Experienced clinicians may do all or just parts of this. The most difficult aspect of the clinical breast examination is considering whether an area of concern represents a benign textural change in breast nodularity which occurs throughout the menstrual cycle or if it represents a malignant mass. (Rationale and Technique of Clinical Breast Examination Karen M. Freund Medscape General Medicine. 2000) http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408932_4 This is why it is important to examine both breasts rather than just the one of concern. Inspection 1. Give a brief overview of examination to patient, including that both breasts will be examined. 2. Have the patient sit on an examination couch. 3. Ask the patient to remove her clothes to her waist, assist only if requested and/or definitely needed. 4. Have the patient relax arms to her side. 5. Examine and explain the inspection of both breasts visually for the following: o Approximate symmetry o Dimpling or retraction of skin o Swelling or discoloration o Orange peel effect on skin o Position of nipple 6. Observe the movement of breast tissue during the following manoeuvres: o Shrug shoulders with hands on hips o Slowly raise arms above head o Leaning forward Palpation 1. Have the patient sit and/or lie supine/flat on the exam table. 2. Ask the patient to remove whatever is covering them and place her hand behind her head on that side. 19 3. Begin to palpate at junction of clavicle(collar bone) and sternum (breast bone) using the pads of the index, middle, and ring fingers. If open sores or discharge are visible, wear gloves. 4. Press breast tissue against the chest wall in small circular motions. Use very light pressure to assess superficial layer, moderate pressure for middle layer and firm pressure for deep layers. 5. Palpate the breast in overlapping vertical strips/ radial or pie fashion/ spiral technique.. Continue until you have covered the entire breast including the axillary "tail" (into the armpit) 6. Palpate around the areola and the depression under the nipple. Only if there is a history of nipple symptoms eg a lump or discharge might the clinician want to examine the nipple. Often clinicians will ask the patient to see if they can express any discharge though a clinician may want to do this themselves. This is done by pressing the nipple gently between thumb and index finger and make note of any discharge. Gloves should be worn for this. 7. Lower the patient's arm and palpate for axillary (armpit) and supraclavicular lymph nodes (behind collar bone). 8. Repeat on the other side. 9. Reassure the patient, let the patient get dressed, sit back down at the desk and then discuss the results of the exam. This whole examination takes 3-6 minutes to do. 20 Female Pelvic/Vaginal examination The following is an adapted version of detailed guidance from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ Working Group on Intimate examinations’ report Gynaecological Examinations: Guidelines for Specialist Practice, 2002 www.rcog.org.uk/resources/public/pdf/WP_GynaeExams4.pdf Summary: Verbal consent should be obtained from all women for pelvic examinations. Pelvic examinations should only be performed in non-English speaking individuals with an interpreter or advocate present except in an emergency. A chaperone should be offered and available for all women regardless of the clinician’s gender. Ideally a chaperone should be a professional but a trained receptionist or secretary is suitable instead. Assistance with dressing should only be given if absolutely necessary. Gloves should be worn on both hands throughout the procedure. Remarks of a personal nature should be avoided throughout the examination. Any request that the procedure should be discontinued should be respected. Chaperones and clinicians should be alert for verbal and non-verbal signs of distress and respond appropriately to them. In the course of a gynaecological consultation, it is usually best if the history is taken with only the patient present, as this will afford maximum confidentiality and enable the doctor to gain the patient’s confidence. Pelvic examinations, whether by male or female doctors, nurses or midwives, should, however, normally be performed in the presence of a female chaperone preferably unrelated to the patient. Women who require an interpreter or who communicate using sign language will obviously require an interpreter during both history taking and examination. A skilled and gentle pelvic examination is a necessary and important part of the diagnosis of most gynaecological conditions. A pelvic examination enables a doctor to assess the vulva, the vagina, the cervix and uterus, the ovaries and the ligamentous structures around the uterus. In symptomatic women, appropriate digital (finger) or speculum examination can be 21 productive, for example, in assessing a patient with prolapse or in evaluating a patient with dyspareunia (pain during intercourse) but the value of routine examination is low and should not normally be performed. Explanation about the contribution of the pelvic examination towards a diagnosis in the context of the presenting complaint is an essential part of the preamble to obtaining informed consent for examination. Verbal consent should be obtained prior to all pelvic examinations. Poor self-esteem and embarrassment may deter obese women from attending gynaecologists. In the assessment of a woman with dyspareunia, valuable information may be obtained by assessing the ability of digital examination to reproduce the discomfort. This is the only situation in gynaecological practice where sexual problems should be discussed during the examination as opposed to before and afterwards. It should be very clear to the patient that any questions asked during the examination are entirely technical, relating to the site and quality of the pain, and that the woman’s feelings and sexual response are not being discussed. Throughout the examination, the doctor should remain alert to verbal and non-verbal indications of distress from the patient. Doctors who are trained to combine the physical examination with an awareness and acknowledgement of the patient’s feelings will learn more about the patient and give rise to fewer complaints. Speculum examinations The reasons for carrying out a speculum examination must be clearly explained to the patient and her verbal permission sought. As the object of speculum examination is inspection of the vulva, vagina and cervix, it may not necessarily be appropriate for such an examination to accompany bimanual palpation on every occasion. Obviously, inspection of the clitoris is indicated in some cases of vulval cancer, female genital mutilation and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. In the course of routine pelvic examination, however, care should be taken to avoid digital contact with the clitoris. The patient will be asked to lie in an appropriate position for the examination. Usually the dorsal position is chosen for examination with a Cusco speculum (patient lying flat on back with legs bent up). The Sims or left-lateral position is used for Sims speculum examination (patient lying on their left side, back towards the doctor who lifts the right leg to insert the speculum). Sometimes pelvic examination in the semi-sitting position provokes less anxiety than examination in the supine position. Whatever position is used, the patient must be made comfortable and 22 provided with as much covering as feasible. It may be easier to preserve an appropriate degree of modesty with the patient lying on her side than on her back, but many women find an unseen approach from the rear most alarming and are less certain where the finger or speculum is going. Whilst in specialist practice it may be helpful in certain clinical scenarios to examine the patient in a standing position in general practice unless the doctor has particular expertise in gynaecology this would not normally be appropriate. Careful thought should be given to the necessity for this and to its appropriate conduct to minimise the additional embarrassment it is likely to induce. Vaginal specula The Cusco speculum and the Sims speculum are the most commonly used, the Cusco being particularly appropriate for cervical inspection and the Sims if a speculum examination is being performed as part of a full gynaecological examination in cases of suspected uterovaginal prolapse and urinary fistula. Cusco Speculum Simms Speculum Specula should be warm but not excessively so. If they are of the metal variety and kept following sterilisation on a cloth over a radiator, held under a warm tap for a few moments or held in the doctor’s gloved hand prior to insertion, the degree of warming will usually be adequate. The temperature of the speculum should be checked after any procedures aimed at warming it to ensure it has not become excessively hot. It is essential that an appropriate size of speculum be used and this may mean that a single-finger assessment of the introitus will need to be performed prior to selecting a speculum. This is particularly important in postmenopausal women or post-operative patients in whom there may be some narrowing of the introitus. A small speculum may be required in the nulliparous or virginal woman, although such examination is rarely indicated in a virgin. Specula appear to some patients to be large, cumbersome and potentially painful instruments – they must be used with gentleness and sensitivity. There is no excuse for fumbling with the 23 instruments. If the examiner is relatively inexperienced in the use of specula, it is essential that he or she practises assembling the instruments prior to insertion rather than subsequently fumbling and causing distress. Some of the disposable plastic devices have a noisy ratchet device which some patients might find unnerving – the ratchet strip can be broken and the speculum used without it if need be. The use of a water-based, nonsticky lubricant such as one of the proprietary clear gels is advisable. Performing a vaginal speculum examination Gloves should be worn on both hands by the examining doctor for all vaginal and speculum examinations. The patient must be told about each manoeuvre prior to it being undertaken. When she is in an appropriate position and is comfortable, she should be told that the examiner is going to examine the vulva, separate the labia and insert the speculum. It should be inserted to its full length and then gently opened, enabling inspection of the cervix. If the cervix is pointing anteriorly (forwards), such as would commonly be the case with a retroverted (tilted backwards) uterus, or deviated to one or other side, a certain amount of adjustment of the position of the blades may be necessary and this should be carried out with great gentleness. Sometimes it will be necessary to use a blunt instrument such as a sponge-holding forceps to gently move the cervix clear of the tips of the speculum blades if an adequate view is to be obtained. Sometimes the speculum is introduced too far and is in either the anterior or posterior fornix (the space in front of and behind the cervix). In this case, the cervix will only appear if the speculum is gently opened and withdrawn. The examination may now proceed, with the taking of swabs from the posterior vaginal fornix or the endocervical canal, if appropriate, and the taking of a cervical smear, should this be indicated. It may be necessary to mop secretions from the cervix in order to obtain a good view of its epithelium. It is important that the patient be told of all these manoeuvres before they are carried out in understandable and non-patronising language. When the operator is happy with the information obtained from speculum inspection of the cervix, the instrument will be slowly and gently withdrawn and the vaginal walls inspected during its withdrawal. There is a danger of trapping the cervix between the blades of the speculum if it is not held open a little as it is withdrawn. When taking cervical the patient must be warned in advance about what the operator is about to do, as some discomfort can result, especially if an endocervical brush is used. She should also be told that there may be some bleeding following the taking of a smear and reassured that this is not usually of any clinical significance. 24 Bimanual abdominal/vaginal examination This is considered by most women to be the most intimate of examinations and its use should be restricted to occasions when it is necessary that such an examination be performed. There are occasions when a speculum examination alone may be carried out but, in a woman with gynaecological symptoms, the two should usually be combined. In order to minimise the inevitable discomfort of bimanual examination and to obtain the most information from the procedure, it is important that the bladder is empty. Gynaecologists should be trained to perform bimanual examination in both the left lateral (lying on left side) and the dorsal (lying flat on back) position, in order to cater for the patient’s personal preference though most GPs would normally examine the patient in a dorsal position. Bearing in mind that it is the abdominal hand that does most of the palpating, it is obviously necessary for as much abdominalwall relaxation to be obtained as is possible. Some patients find it extremely difficult to relax when being subjected to what for them is a most embarrassing procedure. Every effort should be directed to gain the patient’s confidence and reduce her anxiety. It is important that abdominal palpation as part of the bimanual examination procedure commences with the ‘abdominal’ hand relatively high on the abdominal wall, as it would otherwise be possible to miss substantial masses arising from the pelvis. Feeling the outline of the uterus is best achieved by using the vaginal finger or fingers to elevate and bring forward the uterus by means of gently exerting pressure on or behind the cervix. It is not always mandatory to insert more than one finger, especially in very slim patients. The examination is to accurately and consistently delineate the uterine size, shape and contour, especially if the uterus is retroverted. In addition to these features, it should be possible for the examiner to form an impression of the degree of mobility or fixity of the uterus. Following examination of the uterus, the adnexa are palpated bimanually. Normalsized ovaries may not be palpable, especially in the overweight or postmenopausal patient. The right ovary is more readily palpable than the left, which may be difficult to feel if it is lying behind the bowel, particularly if the bowel is loaded. Clinical evidence of tumours may also be detected, together with evidence of ‘cervical excitation pain’, produced by gently moving the cervix and putting the adnexal structures slightly on the stretch. All these procedures must be carried out with extreme gentleness but even if this is achieved and even if a major degree of patient confidence is also obtained, there will inevitably be some discomfort associated with bimanual palpation. The examination may also be uninformative, particularly if the patient is obese or very tense and anxious. At the 25 conclusion of speculum or bimanual examination, the patient should be given some tissue with which to remove any remaining lubricating gel. Ideally, washing facilities and a mirror should be provided so that the patient can dress in comfort and privacy. Thereafter she should be told of the examiner’s findings, once she is seated back in the consulting room. Although the patient, particularly if elderly, may appreciate the presence or help of a nurse or chaperone while she is dressing, it is generally preferable if the consultation subsequent to examination is conducted with only the doctor and patient present, for reasons of confidentiality, unless of course the patient wishes otherwise or needs the services of an interpreter or sign language. A pelvic examination takes between 5-10 minutes to do plus 5 minutes to take a smear and swabs. 26 Rectal examination The following descriptions are edited from Macleods Clinical Examination. Experienced clinicians may do all or just parts of this. Left lateral position for rectal examination Wear gloves Lubricate index finger. Throughout examination be alert for the patient’s discomfort. Position the patient in the left lateral position Reassure the patient that the examination may be uncomfortable but should not be painful. Inspect the anus for haemorrhoids and anal tears Insert finger slowly, assessing external sphincter tone as enter. Rotate finger, palpating along anterior, left, posterior, right walls. Ask patient to squeeze the examining finger. Withdraw finger, inspect for stool colour and presence of blood / mucus Wipe lubricant off pt. 27 Male Genital Examination The following descriptions are edited from an online resources and medical textbooks Experienced clinicians may do all or just parts of this. Penis Gloves on. Retract foreskin if indicated. Rashes, ulcerations, swellings, lesions, warts. Urethral meatus: • Meatus is patent • Meatus is in normal location. • No extra openings (hypospadias). Look for discharge: • Bloody. • Purulent. If discharge, compress penis to express some for swab and culture Scrotum: inspect Gloves on Note size and symmetry Look for rashes, ulcerations, swellings, lesions. Scrotum: palpate Similar size, consistency for R and L. Smoothness, firmness. Absent testicle causes: • Undescended [look in inguinal canal]. • Surgical removal. Masses – palpate around testes to see if testes is separately identifiable and whether an inguinal hernia is likely if not Scrotum: translucency Performed if a mass was palpated. Turn off lights. Hold light up to posterior of swelling, and test for translucency: • Opaque: solid mass. • Translucent: cystic. Examine whether separate from the testis. 28 Lepton & Kirkheaton Surgeries Chaperones Lepton & Kirkheaton Surgeries are committed to providing a safe and comfortable environment where patients and staff can be confident that “Best Practice” guidance as recommended by the General Medical Council of the United Kingdom is being followed at all times and the safety of everyone is of paramount importance. All patients are entitled to have a chaperone present for any consultation, examination or procedure where they feel one is required. A chaperone is often used for intimate examinations to act as a witness, support and safeguard for both the patient and the health care professional. The surgery will endeavour to provide a chaperone at the time of request; however, occasionally it may be necessary to reschedule your appointment to arrange a chaperone. Wherever possible we would ask you to make this request at the time of booking an appointment so that arrangement can be made and your appointment is not delayed in any way. Your healthcare professional may require a chaperone to be present for certain consultations in accordance with our Chaperone Policy. If you would like more information on the use of Chaperones please see our website www.lepton-kirkheatonsurgeries.nhs.uk or contact our Practice Manager to see the full Chaperone Policy reference document. Thank you. 29 References GMC Intimate examinations and chaperones April 2013 http://www.gmcuk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/21168.asp The Medical Protection Society Factsheets- Chaperones England July 2014 http://www.medicalprotection.org/uk/englandfactsheets/chaperones Rationale and Technique of Clinical Breast Examination Karen M. Freund Medscape General Medicine. 2000 http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408932_4 Gynaecological Examinations: Guidelines for Specialist Practice, © Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2002 http://www.rcog.org.uk/resources/public/pdf/WP_GynaeE xams4.pdf Douglas, G, Nicol, F, Robertson, C. Macleod's clinical examination. 12th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. 2009 30