DOCX file of Researcher Mobility among APEC Economies

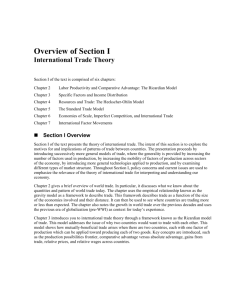

advertisement