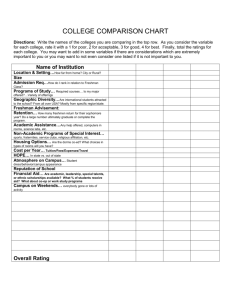

Project Question #1

advertisement