The Days of the Locust

advertisement

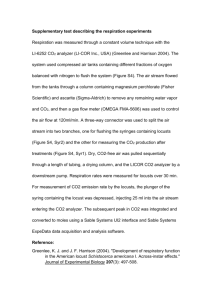

The Days of the Locust The 1870s “grasshopper” plague and its impact on the American countryside Exhbit example Overview Some of us likely read about the Grasshopper Plagues of the 1870s in Laura Ingalls Wilder's On the Banks of Plum Creek. In the chapter, "The Glittering Cloud" Laura gave an excellent account of what it was like to have actually had the hordes of grasshoppers converge on their homestead. One soon understands the hopelessness that pioneer families must have felt as the hoppers consumed virtually everything they had. Although we commonly refer to them as Grasshoppers both then and now, they were actually Rocky Mountain Locusts. In appearance, they look very much like the grasshoppers of today. Much of the prairies were invaded by the millions of Rocky Mountain Locusts. They would fly in in such numbers as to appear to be a cloud blocking the sun. Laura's experience took place in Minnesota but she wrote her books many years later when she lived in southern Missouri. This site is designed to demonstrate the effects that the Rocky Mountain Locust had on the Midwest with special focus on Minnesota and Kansas. Exhbit example Overview (cont.) During the plagues several things were tried to combat the infestation. Mr. J. A. King , of Boulder Colorado, invented the curious suction-fanning machine. It consisted of two large tin tubes, about eight inches in diameter, with flattened, expanded, and lipped mouth-pieces running near the ground. The horizontal opening or mouth was about seven feet long. The tubes connected at the upper extremity with a chamber, in which was a revolving fan that traveled at a speed of 1,200 revolutions per minute. Effectively a giant “vacuum,” the King machine could be made for around $50, and it worked well on smooth ground or in wheat-fields while the wheat was still far from ripe. Exhbit example Overview (cont.) Ultimately the locusts simply disappeared, and the farmers were left to pick up the pieces of their ruined lives. The ‘grasshopper plague’ has enormous impact on the American people. It inflicted great damage on rural America, driving thousands of farm families into ruin. It stimulation research in agricultural sciences to better fight insect damage. And it altered people’s views of the role of state and even national government. All of these aspects are considered in the exhibit. Above all, showing how people reacted to crisis, and how this changed their lives ….. Exhbit example Assumptions •The venue is a Minnesota county historical society. The presumed audience is made up of local and regional residents of all ages. •The budget is modest (less than $20,000 for display objects, cards, and brochure). •The physical space is about 2000 square feet (40 by 50 foot exhibition room) Exhbit example Exhibit Layout Exhbit example Exhibit Sources Annette Atkins, Harvest of Grief (1984) Jeffrey Lockwood, Locust (2004) Thomas Cox, Everything But the Fence Posts (2010) Manuscript letters, photographs US Entomological Society Reports Exhbit example Overview “Behold, tomorrow I will bring the locusts into thy coast, and they shall cover the face of the earth, that one cannot be able to see the earth: and they shall eat the residue of that which is escaped, which remaineth unto you from the hail, and shall eat every tree which groweth for you out of the field . . .” Exodus 10:4-5 Exhbit example The Culprit The Rocky Mountain locust -- Melanoplus spretus, was the dominant ‘grasshopper’ species in Middle America. It ravaged farm crops in North America for decades, but is now apparently extinct. The last living specimen was recorded in 1902. Exhbit example The Victims Before major advances in chemical technology, farmers fought pest infestations with tar and fire. Here, farmers in Kansas, 1870s, burn piles of field stubble mixed with tar and ensnared locusts Exhbit example Background Before the development of chemical pesticides, American agriculture suffered from insect infestations that destroyed millions of dollars worth of crops. In the 1830s the Hessian fly (so named because Hessian mercenaries were said to have carried the insect to North America during the 1770s) did much damage, and the boll weevil continuously plagued the cotton crops of the South. The availability and richness of the land was such that this usually did not lead to food shortages or widespread hunger. American farmland grew in volume, crops grew in size and profits from food harvests fed the growing population and enriched the nation. But in the 1870s a sudden wave of locusts devastated the Midwest, threatening to bring famine and ruin. It began with a tiny creature known as the “Rocky Mountain grasshopper.” Exhbit example The Mystery A small flying grasshopper, the Rocky Mountain locust species was roughly 1.25 to 1.4 inches long, known as the Rocky Mountain Locust. Their native homelands were the dry Rocky Mountain upland region of primarily Colorado, Wyoming and Montana. After hatching out in the spring of the year, the locusts would travel eastward in search of food. When conditions were ideal, they could multiply into the billions, travel over long distances, and consume virtually anything and everything that was remotely edible. In 1874, for unknown reasons, a massive body of the little locusts spread across the Midwest like a Biblical plague. Exhbit example First Signs of Trouble The Year of the Locust began in mid summer, 1874 as millions moved through Kansas and Nebraska. They reached the northwestern corner of Missouri in late July to early August. Damage was rather light in Missouri 1874, but in 1875, the Missouri State Entomologist tallied up enormous losses by county: “Atchison, $700,000; Andrew, $500,000; Bates, $200,000; Barton, $5,000; Benton, $5,000; Buchanan, $2,000,000; Caldwell, $10,000; Cass, $2,000,000; Clay, $800,000; Clinton, $600,000; De Kalb, $200,000; Gentry, $400,000; Newton, $5,000; Pettis, $50,000; Platte, $800,000; Ray, $75,000; Saint Clair, $850,000; Vernon, $75,000; Worth, $10,000. Amounting in the aggregate to something over $15,000,000.” Exhbit example The Crisis The crisis spread across the continent’s center and quickly underscored the limit of public assistance. Exhbit example Stories of Grief Susan Dimond Text transcribed (from Kansas Historical Society Collections), explaining family’s loss of crops to locusts It was so cold the children had to keep close to the stove most all day . . . we are getting along as well as the generality of people I guess have enough to eat & wear & a warm house good bed & bed clothes to keep us warm and that is about all any one can have. Aid is still comeing in slowly some shoes old clothes & some Provisions. we all hope to have good crops another year & if we do not do not know what we will do then, go west I suppose? I wish this was a good enough country to advise people to come to but at present I advise all to keep away. Exhbit example News of the Crisis Exhbit example Aid to Families Kansas’s state government issued scrip (informal currency) for farmers to use for property taxes, but many lost their farms anyway. Exhbit example A Losing Battle? Exhbit example The “hopper-dozers” The most effective weapon against the locusts was sheets of metal, coated with tar, pulled across fields and then dumped on bonfires. It was a slow, exhausting process and only partially effective against swarms amounting to millions of insects. Exhbit example Devastation in Minnesota The locusts overwhelmed fields in Minnesota, doing serious damage in almost every area. In the western and southwestern counties, nearly half of the wheat crops were destroyed and over half of the oat crops (largely used for feeding horse and cows). Many families were completely destitute, and farmers who were unable to pay taxes on their lands were in danger of losing their farms. Exhbit example Government response John Pillsbury, governor of Minnesota from 1876 to 1878, was part of the famous and wealthy Pillsbury family. He refused to recommend extensive aid programs to the state legislature, arguing that “hand-outs” would “undermine the moral fiber of the poor.” The legislature agreed on providing limited aid by delaying the collection of property taxes and providing grain seed to farmers for new planting. Farmers had to agree to pay for the seed (at the rate of $1 a bushel of seed) – the cost of seed to be a “lien upon my crop of grain, raised each year,” until the loan was repaid. Ten bushels of seed would raise (at most) 135 bushels of wheat, worth about $135. Exhbit example Documenting need Farmers applying for county aid under the poor laws had to swear a “pauper's oath” that they were “deserving of relief.” Four witnesses had to sign a note attesting to the applicants “character.” Several farmers stated that they were “made to feel like unsavory miscreants” during the process. Exhbit example Extent of direct aid Most counties granted applicants for assistance about $2 to buy about 10 pounds of pork, some molasses, baking soda, and matches. In 1875 it cost about $200 to maintain a family of four. Exhbit example Evolving defenses The damage done from the locusts resulted in calls for new strategies against insect infestations. Charles Riley (Missouri State entomologist) and Cyrus Thomas (Illinois professor of Agricultural Sciences) called for a Federal office to pursue ways to prevent a repeat of the grasshopper plague. Exhbit example Government growth The US Entomological Commission, established by Congress in 1877, as part of the Interior Department and staffed by Riley, Thomas and Alpheus Packard (above) used Federal funds to find countermeasures to insects – the earliest use of chemicals was part of its efforts, summarized in annual reports until 1902. Exhbit example Legacies The plague of locusts lasted until 1877, when the insects simply disappeared over a period of about a month. At its height the swarm was estimated to contain over 12 trillion insects (enough to cover the whole state of California). Over $200 million of damage (about a billion dollars today). This was not enough to create a famine, but in conjunction with the industrial “panic” of the 1870s, it contributed to unemployment, and left the Midwest battered, as suggested in this 1875 cartoon. The Rocky locust appeared again after 1877, in smaller numbers. No specimen has been found since 1902. Exhbit example Social Cooperation Did the locust plague – and the meager aid given to families during it – change social thought? Perhaps. The influence of Darwin had grown after 1870, to the point that the “survival of the fittest” idea was used to celebrate the power held by the great industrial leaders (Carnegie, Rockefeller, etc. In Illinois (a state that saw much laborindustry violence and some damage from the locusts), the botanist Lester Ward argued in his book Dynamic Sociology (1883) that society could “guide” the development of peoples, rather than just permit them to compete. Exhbit example The Legacy of Scientific Charity In the first half of the 19th century, cities had begun to transform charity work, through 1) The creation of asylums, the idea of “scientific charity” and the “charity organization societies.” 2) The need to develop greater urban efforts in public health. 3) After 1865, the need to integrate the former slaves with the Freedman’s Bureau, etc. 4) The (reluctant) recognition of labor unions by industries and some states. 5) The locust infestation triggered new discussion of charity – the ‘”social gospel” and “social work” profession were some results. Exhbit example Farmers organize The hard times for farmers stimulated an era of rural organization. The Granger movement, the Farmers’ Alliances, and the Populist movement were all influenced by such factors as the locust plague, the high costs that farmers paid to grow and ship their grain, and the low prices they received for their harvests. Farmers’ Alliances called for regulation of railroad shipping costs, reduction of loan interests, and the formation of “rural cooperatives” that could allow farmers to operate their own grain elevators, creameries, and banks. Critics called the farmers’ movements “socialistic” threats to “American freedoms,” but the farmers said they were simply protecting their own interests. Exhbit example Populism and politics In 1896, the Democratic Party (largely out of power since the Civil War) picked William Jennings Bryan, a Nebraska populist, as its presidential candidate. This temporary unification of the populist movement and the Democratic Party did not lead to victory – Bryan was defeated by William McKinley. The 1896 election, however, was a turning point in the Democratic Party’s identity. As the 20th century began, Democratic candidates were increasingly identified with reform movements and a growing philosophy of having government actively intervening in social issues. Exhbit example Labor and Political Issues Urban laborers too became more politically active, influenced by hard times and European ideas. Both railroad strikers and business owners referred to the “Paris Commune” (when French workers called for a revolution against the state) during rail strikes in 1873-74. Owners warned that unions would “bring communism” to American society. Some strikers hoped that this would happen, but most union leaders condemned the idea of revolution. Exhbit example Labor and Industry According to statistics gathered at Princeton University, wages for industrial workers rose 31% from 1860 to 1881, while prices rose 41%. This meant that workers had a harder time paying for things as time went on. Labor unions grew as a result. The Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor (AFL) were growing after 1870. Exhbit example Strikes in 1877 A major collapse of credit in 1872 brought on a financial “panic” – a depression that slowed the pace of growth (the Northern Pacific Railroad stopped work on its route through Dakota Territory to the west). Many businesses began to cut wages in order to save money. This sparked strikes and violence in American industries. Exhbit example Political Machines Many cities had long been controlled by political machines that delivered votes to selected candidates in return for special favors. Reformers aimed to curb the power of machines with voting reform. But some reform groups (and some labor groups who wanted higher wages) also sought to restrict immigration and reduce their votes. One result of this in the 1870s was when the Congress yielded to public pressure and banned Chinese immigration. Exhbit example Later Battles Exhbit example Battling with chemicals By the late nineteenth century, U.S. Farmers had made some progress in fighting insects by using chemicals Straying a ix of copper acetoarsenite (Paris green), or compounds of nicotine sulfate, and sulfur worked in some cases. Not until the widespread use of DDT in the mid-20th century did a reliable system develop. But that raised other questions . . . Exhbit example And the future? The Africa Emergency Locust Project has since the early 2000s provided World Bank aid to North African and Middle East nations that are annually threatened with famine because of insect infestations. Much of the recent protest activity in this part of the world is driven more by hunger than political desires for freedom. Exhbit example Review The “grasshopper” exhibit uses images, text and sound to give visitors some idea of what it was like to live in the 1870s and battle the locusts as they destroyed farms and livelihoods. By placing alongside the basic story enough information on the industrial development of America in the 1870s, the rise of political machines and labor movements, and the subsequent growth of farmer’s protest movements, the museum visitor is allowed to place the events of the grasshopper infestation into context. In this manner, the exhibit will meet the educational goals of Schwab by making the visitor a ‘student,’ the museum a ‘teacher’ and the events of the 1870s a ‘lesson’ (subject matter about the nation’s rural past. Highlighting how ordinary people were ruined in the 5 years of locust invasions should strike a chord for many viewers. Exhbit example Review (cont.) The exhibit reflects Huebner’s ideas about the criteria for learning – the scientific and technical aspects of the exhibit are mirrored in the display of ‘hopper killer’ machines invented to fight the locusts. At a deeper level, the use of sound (the constant ‘chirp’ in the exhibit room) and the odor of burnt tar/insects will reflect Huebner’s concerns for aesthetics and Schwab’s concept of the learning “milieu.” In should in fact impress on the museum-goer a sense of memory similar to what the victims of the locust plague recalled for the rest of their lives. Exhbit example