mcl_mankiw_intro_micro_chapter_17_fall_2012

advertisement

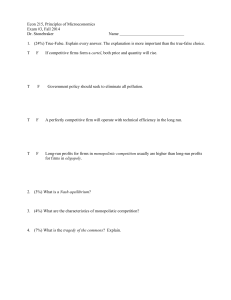

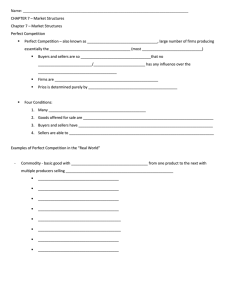

Lecture Notes: Econ 203 Introductory Microeconomics Lecture/Chapter 17: Oligopoly M. Cary Leahey Manhattan College Fall 2012 Goals • We now look at oligopoly, another form of imperfectly competition. • We examine issues of cooperation among these kinds of firms. • The use of game theory will help us understand why these kinds of firms find it difficult to cooperate • We look at the policy record, namely antitrust policy to deal with these kinds of firms. 2 Measuring market concentration • To figure study the importance of possible oligopolies in particular industries, we examine concentration ratios. • The concentration ratio is the percentage of the market’s (or industry’s) total output supplied by the four largest firms. • A larger concentration ratio means less competition. • Oligopoly is a market structure with a high concentration ratio. • High concentration ratios cover a wide variety of industries, ranging from autos (79%), to cigarettes (89%), to video game consoles (100%). 3 Oligopoly • Oligopoly is a market structure with only a few sells offer similar or identical products. • The small size of the firms in the markets means that each firm needs to consider how its competitors will react to his decisions regarding price and quantity. So the oligopolist must think strategically. • Game theory is the study of strategic behavior and hence is entwined with the study of oligopoly. 4 Example: cell phone duopoly in smalltown P Q $0 140 Smalltown has 140 residents The “good”: cell phone service with unlimited anytime minutes and free phone 5 130 10 120 Smalltown’s demand schedule 15 110 Two firms: T-Mobile, Verizon 20 100 (duopoly: an oligopoly with two firms) 25 90 Each firm’s costs: FC = $0, MC = $10 30 80 35 70 40 60 45 50 Example: cell phone duopoly in smalltown P Q Revenue Cost Profit $0 140 5 130 650 1,300 –650 10 120 1,200 1,200 0 15 110 1,650 1,100 550 20 100 2,000 1,000 1,000 25 90 2,250 900 1,350 30 80 2,400 800 1,600 35 70 2,450 700 1,750 40 60 2,400 600 1,800 45 50 2,250 500 1,750 $0 $1,400 –1,400 Competitive outcome: P = MC = $10 Q = 120 Profit = $0 Monopoly outcome: P = $40 Q = 60 Profit = $1,800 Example: cell phone duopoly in smalltown • One possible duopoly outcome: collusion • Collusion: an agreement among firms in a market about quantities to produce or prices to charge • T-Mobile and Verizon could agree to each produce half of the monopoly output: – For each firm: Q = 30, P = $40, profits = $900 • Cartel: a group of firms acting in unison, e.g., T-Mobile and Verizon in the outcome with collusion Collusion versus self-interest • Both firms in the duopoly example would be better off to stick to an agreement, such as splitting the monopoly • However, each firm has an incentives to renege on the agreement. • So it is difficult for firms to form cartels and honor their agreements. • It is impressive that the “oil cartel” has held up so well, in part because Saudi Arabia is the swing producer and implicit “enforcer.” 8 Equilibrium for a oligopoly • A situation is which the economic participants (firms) interact with one another, choosing their best strategy given the strategies of others is called a Nash equilibrium. • In the duopoly example, the Nash equilibrium is when each firm produces Q = 40: • Given Verizon’s output of 40, T-Mobile’s best move is also to produce 40. • Given that T-Mobile produces 40, Verizon’s best move is stay at 40 and not to cheat on the implicit agreement. 9 Comparison of market outcomes • When firms in a oligopoly individually choose production (do not collude) to maximize profit, then • Oligopoly output is higher than monopoly output but less than competitive output. • Oligopoly price is lower than monopoly price but higher than competitive price. 10 Output decision involves both quantity and price effects • Changing output has two effects on a firms profit (like the monopoly case). • The output effect: P > MC, increase output increases profit. • Price effect: Raising output increased quantity sold at at the “cost” of lower prices and reduced profit on all units sold. • If output effect > price effect, output is increased • If output effect < price effects, output is decreased. 11 Game theory • Game theory is useful in understanding oligopoly behavior as well as other situations in which players interact and behave strategically. Some terms. • Dominant strategy: a strategy that is best for for a player in a game regardless of the strategies chosen by others. • Prisoner’s dilemma is a game between two captured criminals that illustrates why cooperation is difficult even when it is mutually beneficial. 12 Prisoners’ dilemma example The police have caught Bonnie and Clyde, two suspected bank robbers, but only have enough evidence to imprison each for 1 year. The police question each in separate rooms, offer each the following deal: If you confess and implicate your partner, you go free. If you do not confess but your partner implicates you, you get 20 years in prison. If you both confess, each gets 8 years in prison 13 Prisoners’ dilemma example Confessing is the dominant strategy for both players. Nash equilibrium: both confess Bonnie’s decision Confess Confess Clyde’s decision Remain silent Bonnie gets 8 years Clyde gets 8 years Bonnie goes free Remain silent Clyde gets 20 years Bonnie gets 20 years Clyde goes free Bonnie gets 1 year Clyde gets 1 year Prisoners’ dilemma example • The outcome is usually that both confess and get 8 years in prison. • Both would have been better off not confessing and getting only 1 – year sentences. • But even if they had agreed before hand not to confess, the logic of self-interest takes over and leads them to confess. 15 Oligopoly behavior as prisoners’ dilemma • When oligopolies form a cartel in hope of sharing the monopoly outcome, they became stuck in a prisoners’ dilemma. • In our earlier example of the cell phone duopoly, the two firms decided to split the monopoly outcome of Q = 30. • The next slide shows the payoff matrix. • Other examples of prisoners’ dilemma in oligopoly behavior: • Airline fare wars • Ad wars • OPEC • Arms races • Common resources 16 The prisoners’ dilemma: payoff matrix Each firm’s dominant strategy: renege on agreement, produce Q = 40. T-Mobile Q = 30 Q = 30 Verizon Q = 40 T-Mobile’s profit = $900 Verizon’s profit = $900 T-Mobile’s profit = $750 Verizon’s profit = $1000 Q = 40 T-Mobile’s profit = $1000 Verizon’s profit = $750 T-Mobile’s profit = $800 Verizon’s profit = $800 Prisoners’ dilemma and societal welfare • The noncooperative (non-cartel) oligopoly equilibrium: • Bad for oligopoly firms as they cannot split the monopoly profits. • Good for societal and Q is closer to socially efficient output and P is closer to MC • But in other prisoners'’ dilemma example, such as the arms race, the inability to cooperate may reduce societal welfare. • Cooperation is possible after learning and being repeatedly “burned.” 18 Public policy toward oligopolies • With output too low and price too high in an oligopolistic equilibrium relative to the societal optimum, there is a role for public policy. • Public policy can promote competition and prevent cooperation to bring the market outcome closer to the desired societal outcome. • Restraint of trade and anti-trust laws (Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 and the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914) are the best known historical examples with T Roosevelt the famed “trust-buster.” • Most agree than price-fixing agreements should be illegal. • But there is concern that anti-trust enforcement goes “too far” and may stifle “legitimate” business practices. 19 Antitrust policy and resale price maintenance • At first blush retail price maintenance, allowing imposing lower limits on prices retailers can charge appears to reduce competition at he retail level. For example warranties only honored at “authorized” retailers that agree to sell below an authorized price. • But market power at the wholesale level by manufacturers does not necessarily spillover to benefit at the retail level. • This practice has a legitimate business end in restricting free loading, in which discount firms “free ride” off of the expenses incurred in servicing customers at full-service retailers. 20 Predatory pricing and bundling/typing • Predatory pricing occur when a firm sells at below cost to prevent entry or drive a competitor out of business and hen charge monopoly prices later. • While this is illegal, it is hard to tell, when a price cut is predatory or rather beneficial to customers. It is in the short-run. • Some skepticism about the virtues of predatory pricing as it is costly in the short-run and can backfire. • Bundling or tying develops when a manufacturing sells a number of products in a bundle. • Critics worry that it gives firms market power by connecting weak products with stronger ones. Others counter that consumer will not pay more more two products together or bought separately. 21 Summary and conclusion • Oligopolies can end up looking like monopolies or like perfect competitors depending on the number of firms and how cooperative the behavior is. • Prisoners’ dilemma show how hard cooperation is, when when it is in all participants best interest. • Public policy can employ antitrust laws to increase competition and prevent predatory pricing. The scope of those actions is controversial. • Oligopolies maximize profit if they cooperate and form a cartel and split the monopoly profits. • However, self interest leads to an output of greater output and lower price, close to the societal desired outcome. The more firms and the less cooperation leads to a more competitive outcome. 22