HLPE comments IATP - Food and Agriculture Organization of the

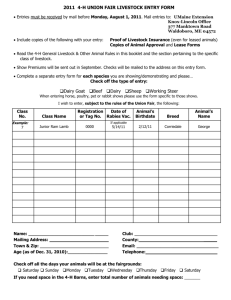

advertisement