paper - African Development Bank

advertisement

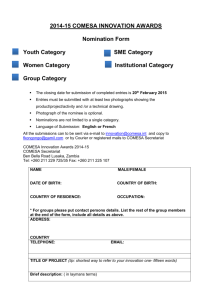

Performance of Intra-COMESA Trade Integration: A comparative Study with ASEAN’s Trade Integration Abstract This paper aims at assessing the performance of intra-COMESA trade integration on the basis of success of ASEAN integration, using an out-of-sample approach. The analysis employed gravity model to estimate the coefficients of ASEAN model which are used as a benchmark to project the potential trade for eight COMESA member states. The success of COMESA is estimated by the ratio of potential to actual trade. The results pointed out that all countries of the selected sample are far from their potential trade level, implying unfavorable performance of the regional trade integration among COMESA members. The results also indicate that the gap between potential and actual trade has been decreased in last decade, suggesting a convergence toward the potential trade level over time. Finally, the paper ends with some policy recommendations regarding promoting regional cooperation among COMESA member states. Keywords: Regional integration, ASEAN, COMESA, Gravity model JEL Classification: F14, F15. 1 1. Introduction Regional integration (RI) has been considered as one of the prominent strategies for development among countries and regions. It is well known that RI brings countries with many advantages in terms of economic and political aspects. Indeed, RI promotes economic growth and industrialization process through fostering intra-regional trade, infrastructure and investment. Precisely, RI provides a huge market for parallel development of new industries which reduces external vulnerability through increasing bargaining power and in turn, increases the national income (Balassa, 1961). Moreover, regional trade cooperation between countries is regarded as a key strategy to confront the challenges of globalization. The history of regional cooperation involves a number of successful regional trade schemes in developed and developing regions. For example, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is classified as one of the most successful trade integrations in the World. Since its establishment in 1967, ASEAN has achieved remarkable cooperation progress in terms of economic, social and political fronts. The intra-trade performance also witnessed notable improvement, supported by the adoption of many trade arrangements, including ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) in 1992, with aim to remove tariff and non-tariff barriers within the region. As result, intra-ASEAN trade has increased from 20% in to 25% in 2009 (ASEAN Secretariat, 2009). In Africa, the Common Market for East and Southern Africa (COMESA) is one of the prominent regional bodies in East and South Africa. The main objective of COMESA is promoting trade, investment and infrastructure. The COMESA integration has paid considerable attention to cooperation in productive sectors such as, infrastructure, agriculture, transportation and financial sector. In last decade, COMESA leaders launched many regional cooperation arrangements, including Free Trade Area (FTA) in 2000 as well as custom union in 2009. Furthermore, the aspiration of the leaders is to push the cooperation process toward a Common Market and economic community in the coming decade. Having these ambitious plans for further trade cooperation, it is 2 important to assess the success of COMESA regional trade integration in comparison with other successful trade integration. Therefore, investigating the performance of intraCOMESA trade on the basis of success of ASEAN integration, it would be useful to gauge the prospect of COMESA for further trade integration and to uncover some policies that can help Africa policy makers to develop the process of the integration so as to achieve more economic cooperation. The ASEAN is selected because it is one of the most successful regional integrations in developing regions (i.e. Eastern and Southern Asia). ASEAN also similar to COMESA as it started with trade integration as main pillar for economic cooperation as well as social and political integration. Based on the above, the analysis concentrates on three questions which include: i) How much trade could be achieved among COMESA members if their trade elasticity with respect to economic and geographic variables (economic size, distance, common border, language, colony links) were similar to those achieved in intra-ASEAN trade (This indicates the potential trade)? ii) What is the nature of difference between actual trade and potential regional trade of COMESA member states? To answer these questions, the paper uses gravity model and out of sample approach to investigate the trend of intraCOMESA trade achievement compared with regional integration of ASEAN. The importance of this study is to fill the gap in literature on understanding the success of regional integration in Africa in general and COMESA region, in particular. In addition, unlike the previous studies on measuring trade potential, this study use “out-of-sample” approach, which did not used before to analyze the potential intra-trade of COMESA. To our knowledge this method of projecting potential trade is only used by Patore et al. (2009) to compare the parallel integration process of EU with the Mediterranean countries and Central and Eastern European countries. The paper is organized in six sections as follows. Section two outlines some stylized facts about COMESA and ASEAN integration. Section three reviews the empirical literature on regional integration. While section four outlines the research methodology, section 3 five presents the empirical results. Finally, section six ends with conclusion and policy implications. 2. Some Stylized Facts about COMESA and ASEAN integration Before analyzing the success of intra-COMESA trade integration in comparison with the experience of ASEAN integration, it is useful to describe the features of COMESA and ASEAN. Thus, this section outlines the main characteristics of the two agreements, focusing on their memberships, objectives and economic size as well as their regional trade patterns. 2.1. COMESA Regional Integration COMESA started as a preferential trade area (PTA) in 1982 and extended in 1994 to be one of the prominent regional integration bodies in Eastern and Southern Africa. COMESA now embodies 19 members including Angola, Burundi, Comoros, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Seychelles, Sudan, Rwanda, Swaziland, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The main aim of COMESA is strengthening the process of regional economic integration, which had been initiated in order to help member states achieve sustainable economic growth. In 2000, the members of COMESA signed the Free Trade Area (FTA) agreement, to attain sustainable growth of the member states, to promote joint development in all fields of economic activity, to cooperate in the creation of an enabling environment for foreign, cross-border and domestic investment and in the promotion of peace, security, and stability among the member states in order to enhance the economic development in the region (COMESA, 2013). Members of the FTA include eleven countries are: Burundi, Djibouti, Egypt, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Rwanda, Sudan, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Libya and Comoros joined the FTA in 2005 and 2006 respectively, bringing the number of COMESA members included in the FTA to 13 out of 19, other countries trade on preferential terms (COMESA, 2013). In recent decade, the COMESA agreement witnessed an adoption of many trade arrangements with respect to all trade sectors. In 2009 the agreement had launched the 4 custom union which expected to be extended to economic and currency union in the coming decade. Although the growing importance of COMESA in the economy of its members, there are many challenges hider the intra-regional trade. These constraints include conflicting objectives of overlapping regional integrations, lack of political commitment and inadequate infrastructure and information (Khandelwal, 2004 and Oyejide, 1997). For example, most of COMESA countries are members in more than one trade organization in the region such as, East African Community (EAC) and SADC. Regarding the economic and trade performance of COMESA, Table 1 show some basic indicators about COMESA integration. The Table reveals that COMESA region contains about 456 million of inhabitants which they are vary widely from country to another, ranging from less than 90 000 in Seychelles to 87 million Ethiopia. The level of economic situation measured by GDP per capita is also varies widely among COMESA members. For some members like Sudan and Zambia the per capita income increase by the rate more than 200% during the period 2000-2010. While some countries like Congo and Burundi exhibit low levels of GDP per capita, others like Libya and Seychelles reported high level of GDP per capita. In accordance with regional trade performance, Table 1 also shows that COMESA undergone a sizable increase in the intra-regional exports and imports between 2000 and 2010. In 2010 the intra exports of some countries like Egypt and Kenya are very high, while for other countries, exports to the region are far lower. For example, the intraCOMESA exports performance for Comoros, Eritrea and Seychelles did not exceed 2.5 million dollars. The share of Egypt’ exports to other COMESA members have risen from 113.8 million dollars in 2000 to 2343.7 million dollars in 2010, reporting a highest rate in COMESA. Kenya also reported notable increase in intra-COMESA exports from about 595.7$ millions to 1658.4$ millions in 2010. Overall, Egypt and Kenya were the active trading partners amongst COMESA states, as their contribution to total trade in 2010 accounted for 19% and 12.4%, respectively. On the other hand, Libya and Zambia were the highest imported countries within COMESA. The increase of both exports and 5 imports for all countries between 2000 and 2010 indicate that the creation of the FTA in 2000 has resulted in improvement of intra-COMESA trade. Table 1: COMESA Regional Integration, Selected Indicators, 2000 - 2010 Member Population GDP per capita Intra-COMESA Intra-COMESA Share in Total State (million) (USD) Exports- in Imports- in COMESA trade USD million USD million (%) 2010 2000 2010 2000 2010 2000 2010 2000 2010 Burundi 9.23 130.42 219.53 5.01 24.57 19.92 105.87 0.80 0.75 Comoros 20.62 583.09 1090.38 0.10 2.45 5.03 13.01 0.16 0.09 Congo 62.19 91.70 210.77 33.69 1134.3 107.12 806.13 4.52 11.17 Djibouti 0.83 762.54 1353.19 4.08 601.73 73.43 78.15 2.49 3.91 Egypt 78.08 1509.58 2803.53 113.79 2343.67 239.08 961.77 11.32 19.02 Eritrea 5.74 179.31 368.75 0.18 2.14 7.80 155.54 0.26 0.91 Ethiopia 87.10 123.89 341.08 155.14 287.30 107.58 286.24 8.43 3.30 Kenya 40.91 406.12 787.06 595.65 1658.40 77.33 504.09 21.60 12.44 Libya 6.04 6548.57 10455.57 50.41 334.78 69.29 1378.27 3.84 9.86 Madagascar 21.08 246.28 419.22 19.06 47.09 63.47 197.27 2.65 1.41 Malawi 15.01 154.00 359.58 41.51 215.56 52.78 231.83 3.03 2.57 Mauritius 1.28 3861.04 7586.97 96.82 155.74 58.30 125.31 4.98 1.62 Rwanda 10.84 206.65 519.02 35.07 82.73 28.65 415.23 2.04 2.87 Seychelles 0.09 7578.83 10842.57 2.39 2.46 12.52 46.98 0.48 0.28 Sudan 35.65 356.50 1421.09 78.71 336.49 201.21 767.93 8.98 6.36 Swaziland 1.19 1433.18 3093.54 64.98 140.25 0.53 10.67 2.10 0.87 Uganda 33.99 255.12 505.99 77.07 712.98 152.36 586.94 7.36 7.48 Zambia 13.22 322.10 1224.95 152.13 690.18 85.26 1394.23 7.62 12.00 Zimbabwe 13.08 535.04 568.43 170.72 266.96 57.70 271.20 7.33 3.10 COMESA 456.17 25283.9 44171.24 1696.5 9039.83 1419.35 8336.63 100.00 100.00 Source: Authors' calculations based on data from World Bank Indicators and websites of COMESA (comstat.comesa.int/DataQuery.aspx). 6 2.2. ASEAN Regional Integration The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established in 1967, to accelerate the economic growth, social progress and cultural development in the region, establish peace and stability through justice amongst its member nations, promote active collaboration and mutual assistance on matters of common interest in the economic, social, cultural, technical, scientific and administrative fields. The founding countries are Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. Brunei Darussalam joined in 1984, Vietnam (1995), Laos PDR and Myanmar (1997) and Cambodia (1999), making up what is today the ten member states of ASEAN (ASEAN Secretariat (2013). ASEAN has adopted many trade arrangements which resulted in remarkable progress in intra-trade performance, over the last decades (See Table 2). For example, ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) was signed in January 1992 with the aim of creating a free trade area by 2008. The original signatories were: Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. Vietnam joined in 1995, Laos and Myanmar in 1997 and Cambodia in 1999. This free market trade means that all ASEAN goods can be traded to member state’s market with a minimum tariff or without tariff (ASEAN Secretariat, 2013). Table 2 shows that the ten countries that are members of ASEAN have growing economies with population of about 593 million. We notice that the levels of development in two periods are very different across these countries with GDP per capita spanning in the selected periods, from USD 23814.56 to 268.432 in 2000, and from USD 44862.8 to 706.4 in 2010, in Singapore and Myanmar, respectively. The Table shows that the last four countries joined to ASEAN Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam have a lower stage in economic development than the other six member countries. It is interesting to note that for ASEAN countries there is a large and growing disparity between the share of intra-regional exports and the share of intra-regional imports, Singapore was first, followed by Malaysia and Thailand, though it should be noted that Singapore’s share was particularly high as it handles considerable intra-regional trade, 7 and far lowest for Lao PDR and Cambodia. In addition, the share of Singapore’s in total trade within ASEAN reporting a highest rate (34%). Table 2: ASEAN Regional Integration, Selected Indicators, 2000 - 2010 Member Population GDP per capita Intra-ASEAN Intra-ASEAN Share in Total State (million) (USD) Imports- in Imports- in ASEAN trade USD million USD million (%) 2010 2000 2010 2010 2010 2010 Brunei 0.40 18086.60 29915.3 8,615.4 2,383.8 0.54 Cambodia 14.36 298.95 785.1 5,583.6 4,896.8 0.51 Indonesia 240.68 789.81 3027.2 157,779.1 135,663.3 14.34 Lao PDR 6.40 321.29 1099.9 2,432.8 2,076.4 0.22 Malaysia 28.28 4004.56 8555.5 198,800.8 164,733.5 17.77 Myanmar 51.93 268.432 706.4 7,599.5 4,198.7 0.58 Philippines 93.44 1043.46 2129.4 51,431.7 58,228.6 5.36 Singapore 5.08 23814.56 44862.8 371,194.3 328,078.9 34.18 Thailand 66.40 1968.54 4743.3 195,312.3 189,728.4 18.82 Viet Nam 86.93 401.55 1225.5 72,191.9 84,801.2 7.67 ASEAN 593.90 50997.74 3152.8 1,070,941.4 974,789.6 100.00 Source: ASEAN Finance and Macro-economic Surveillance Unit Database, websites of ASEAN Member States' national statistics offices and World Bank Indicators. Regarding the share of ASEAN integration in World exports, Annex I reveals that ASEAN members contribute significantly to total world exports compared with COMESA integration. The contribution of ASEAN to World exports is 1.55% on average over the period 2000-2010, while the share of COMESA accounts only for about 0.03% (See Annex I). 3. Literature Review Having the importance of regional trade integration in economic and political relations between countries, a huge body of literature on assessing the performance of intraregional trade has grown in last decades. Most of empirical studies have focused on 8 measuring the potential trade for trade blocs across developing and developed countries. Although most of the empirical work has been done for European, Latin American and Asian countries, a few studies have been done using African trade data. In this section, however we review some of the empirical studies that are relevant for our paper. Al-Atrash and Yousef (2000) used gravity model investigated the trade performance for 18 Arab countries with 43 others countries that represent over 90 percent of the exports and imports of the Arab world. They found that the intra-trade within the Arab subgroups is higher than overall intra-Arab trade. Also they found that cultural attributes measured by language have mixed effect: while English-speaking countries tend to trade more with each other, the French-speaking countries are not statistically significant. Moreover, their results pointed out that ASEAN preference arrangement exerts large positive effect on Arab trade, while the EU arrangements decrease the volume of trade. Chauvin and Gaulier (2001) measured the potential of increasing intra-SADC trade, using three complementary approaches. The first two ones refer to trade indices which are export diversification indices, and revealed comparative advantages and trade complementarity indices, while the last one is based on gravity model. They found that there is some complementarity between SADC countries; but does not confirm the existence of potential trade. In addition, South Africa is found to be the most significant member in terms of export and can play further role in fostering the intra-trade in SADC region. Khandelwal (2004) studied the prospects and challenges for trade expansion in COMESA and South African Development Community (SADC). He finds that the COMESA FTA has taken a market-liberalization approach to regional integration, but has been hampered by country-level implementation issues. On the other hand, SADC has taken the approach of addressing infrastructure and supply constraints but has also had implementation problems. He also finds that possibilities of growth in intraregional trade may be limited, but that the two arrangements provide opportunities for their member states to adopt 9 policy credibility for trade reforms and trade liberalization and to address structural problems. Pastore et al. (2009) examined the performance of EU members with the Mediterranean (MED) countries and the new EU members using a gravity model of intra-EU trade including 13 members during the period 1995-2002. Employing out of sample methodology they reports that There is a sizeable and unexploited trade potential with both groups of partners, but the ratio of potential to actual trade with the MED countries is much larger more dispersed and stable compared to that with the new EU members. Their results also indicate that the potential tends to converge to actual trade in a much longer time in the case of MED countries. Simwaka (2011) used a gravity model to assess the success of SADC FTA over the period 1998-2007. He separated the data sample into two periods; pre-integration that before the adoption of FTA (1998-2000) and post-integration that after SADC FTA came into operation (2003-2007). He found that the predicted trade is higher than the observed intra-regional trade, suggesting an existence of trade potential among member states. Therefore, they conclude that SADC FTA leads to trade creation and enhance the trade capabilities of member countries. His results, however contradicts the findings by Chauvin (2002) who found that SADC trade potentials are rather small or negative, especially for South African exports. Finally, comparing SADC with other regional integrations, Simwaka argued that ASEAN and NAFTA perform better than SADC. Stack and Pentecost (2011) used a gravity model of new trade theory determinants for a for twenty OECD trading partners countries with EU countries over the period 19922003. Based on out-of-sample approach they project the trade volumes for ten new member states and ten associated countries. Their findings revealed that the projected trade ratios for the ten new member states are multiples of actual 2003 levels, indicating that trade expansion between these countries tend to continue. On other hand, for the Mediterranean countries the ratio of potential to actual trade is found to be near unity value, implying fewer opportunities for further trade integration with the EU. 10 4. Methodology and Data To examine the performance of intra-COMESA regional trade on the basis of success of ASEAN integration, the analysis proceeds via two steps: first, we estimate the coefficients of a gravity model of intra-ASEAN trade, and then we apply them into equations of trade between the selected sample of COMESA members to calculate the potential trade relative to intra-ASEAN trade. The calculated potential trade volume will be compared with the actual volume of intra-COMESA trade. 4.1. Gravity Model Specification The gravity model of bilateral trade is widely used in the literature to investigate the determinants of bilateral trade flow. The gravity model was firstly used by Tinbergen (1962) and Linneman (1966) and later developed by (Anderson, 1979). In recent decades this model has been developed further and used extensively in trade literature. The paper employs the gravity model as benchmark to compare between ASEAN and COMESA intra-trade integration. The gravity model of trade is derived from Newton’s gravity law in Physics, which postulate that there is a gravitational pull between two physical bodies as proportional to their mass and inversely proportional to their distance. This theory is analogous to the international trade as follows: the trade flow between two countries (exporter and importer) is proportional to the product of each country’s (economic mass) commonly measured by GDP, divided by the distance between the country’s respective centers of gravity. Thus, trade between two countries depends on their Gross Domestic Product (GDP), population size and the distance between them. Hence, the estimable gravity model that used in our analysis could be specified as follows: 𝐿𝑛 𝑇𝑖𝑗𝑡 = 𝛼𝑖𝑗 + 𝛽1 𝐿𝑛 𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽2 𝐿𝑛 𝑃𝑂𝑃𝑖𝑡 + 𝛽3 𝐿𝑛 𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑗𝑡 + 𝛽4 𝐿𝑛 𝑃𝑂𝑃𝑗𝑡 + 𝛽5 𝐿𝑛 𝐷𝐼𝑆𝑖𝑗 + 𝛽6 𝐶𝐵𝑖𝑗 + 𝛽7 𝐶𝐿𝑖𝑗 + 𝜇𝑖𝑗𝑡 (1) Where i indicates the reporter countries, j are the trading partners and t is period under consideration, i.e. 1998-2010, Xij is the trade variable between country i and country j; 11 POPi and POPj are the populations at time t of country i and j respectively; GDPi and GDPj are gross domestic product of country i and j at time t; Dij is the geographical distance in kilometers between the capital city of country i and of country j; CL is a dummy variable to capture common language or colonial history, taking value of 1 if the two countries speak same language or have ex-colony links, and zero otherwise. CB is a dummy taking a value of one if the trade partners share a common land borders or sea borders, and zero otherwise; finally, 𝜇𝑖𝑗𝑡 is the error term. All the variables are expressed in natural logarithms except dummy variables. According to the theory, the coefficient of GDP is expected to be positive, as an increase of national income indicates more imports demand and exports supply. The impact of population size (POP) is mixed as suggested by most of previous empirical studies. Markheim (1994) argues that a country with large population size entails a large domestic market and high degree of self-sufficiency and less need to trade (absorption effect). Other argument show that, a large population means more progress in specialization and division of labour and increase of the production, which are generally associated with a larger need for trading (scale effect). The coefficient of distance is expected to be negative, as the larger physical distance between two countries’ economic centers, the higher is the cost of transporting goods between them. Finally, the dummy variable CL and CB are expected to be positive, as sharing borders, ex-colony links, and same language indicate geographical closeness, better information, same cultures and institutions as well as legal systems. 4.2. Data Sources The data used in the gravity model of intra-ASEAN trade spans over the period 19982010 and involves eight ASEAN countries1. On the other hand the data for COMESA member states covers eight countries over the period 2004-20112. The trade data for ASEAN members are extracted from IMF’ Direction of International Trade statistics, 1 The analysis of intra-ASEAN includes: Brunei, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. The remaining countries were excluded, because they joined ASEAN integration after 1998. 2 Due to the lack of data for some COMESA’ countries, the projection of intra-COMESA trade integration involve eight countries: Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mauritius, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. 12 while the data for COMESA are collected from COMSTAT Database website. The data about current GDP and population size are collected from World Bank’ Development Indicators. Data on distance between countries is calculated based on the country location provided by the CIA World Fact-book. Finally, Information about common language, excolony history and common border were sourced from the CIA World Fact-book. 4.3. Estimation Methodology The gravity model in equation (1) is estimated via the panel data methods namely, pooled, fixed effects (FE) and random effects (RE) models. As our regression models involve individual effects, it is important to decide whether they are fixed of random; thus we focus on the fixed and random effects models. When estimating the trade flows between a randomly selected sample of trading partners from a large population a random effects is more appropriate, while fixed effects model is better when estimating the flows of trade between an ex ante predetermined selection of countries (Egger, 2006). This paper aims at identifying the determinants of regional trade between eight ASEAN members; thus fixed effects would be appropriate than random effects model. The eight members were selected based on the availability of trade statistics during the period 1998-2010. However, the Hausman test statistic is applied to check further whether the fixed effects model is more appropriate than the random effects model. If the null hypothesis of no correlation between the individual effects and regressors is rejected, then fixed effects model is better than the random effects model. Following (Simwaka (2011) and Pastore et al. (2009)), the gravity model estimators are used as a benchmark to assess the potential trade of COMESA regional integration. That is, to assess the performance of intra-COMESA trade, the estimated coefficients of gravity model relative to the intra-ASEAN trade model will be applied to the similar specification of intra-COMESA trade model. The success of intra-COMESA trade integration is measured by the ratio of potential to actual trade. As the projected potential trade is the amount of trade that would be achieved if COMESA can achieves the intraregional trade integration similar to the ASEAN. The ratio of potential trade to actual trade measures the success of intra-COMESA trade integration relative to intra-ASEAN 13 trade integration. A ratio of one indicates that the potential trade equals actual trade, implying that intra-COMESA trade is at successful level compared to intra-ASEAN. The higher is the ratio, the higher is the gap that needs to be filled by creation more trade. A ratio less than one indicate that actual trade is close to its potential level. 5. Empirical Results 5.1. Estimation of Gravity Model The results of estimation of gravity model in equation (1) using pooled, fixed effects and random effects models are presented in Table 3. The results in the second column of Table 3 are those of the pooled panel data model. The shortcoming of this model is that it does not consider for heterogeneity of countries, and no country specific effects are estimated, hence assumes that all countries are homogenous in terms of cross-section and time. Column three and five presents the results of the fixed effects models which take into account the heterogeneity by estimating country specific effects. To support the efficiency of fixed effects, the F-test was performed to check the poolability of the data3. The result of the F-test shows that the null hypothesis of equality of the individual effects is rejected, suggesting that a model with individual effects must be selected (i.e. fixed effects or random). Finally, the results in column 4 and 6 are those of the random effects model. The main advantages of random effects model are: like fixed effects it allows heterogeneity in the cross section, but it avoids the loss of degrees of freedom which occurs in fixed effects. To choose between the FE and the RE models, the Hausman test rejects the hypothesis that the coefficients of the FE models and the RE models are equal, suggesting that FE estimates are more consistent. Nevertheless, the RE estimates are more efficient than the FE estimates, but they are inconsistent (Pastore et al., 2009). 3 The pooled model is the (αij = α ) and same parameters over time and across trading partners, while the unrestricted model allows an intercept and other parameters to vary across trading partners () 14 One problem with a fixed effects model is that variables that do not change over time (e.g. distance, common border or common language) cannot be estimated directly because they are fixed effects and are therefore removed in estimates at the difference. Since both time varying and time invariant effects must be taken into account in the gravity model, we follow (Pastore et al., 2009) in relying on the RE models instead of FE model. Precisely, we rely on RE model of column 6 which takes into account all variables specified in our gravity model. Table 3: Results of Gravity model estimation for intra-ASEAN trade (1998-2010) Variable Constant LOG(GDPI) LOG(POPI) LOG(GDPJ) LOG(POPJ) LOG(DIS) CL CB R2 F Hausman Test No of Observation No of Groups Obs per group The dependent Variable is the total trade 2 3 4 5 6 Pooled FEM REM FEM REM -50.26*** 2.20 -32.67*** -80.64 -18.12*** (-12.36) (0.06) (-3.63) (-0.58) (-4.07) 1.32*** -2.72*** 0.94*** -2.65** 0.09* (10.16) (-3.03) (4.29) (-2.94) (1.76) 0.36*** 3.96 0.08*** (3.34) (0.75) (2.88) 1.49*** 3.40*** 1.46*** 3.42*** 0.17*** (11.76) (3.88) (6.77) (3.87) (5.73) 0.14 0.86 0.03 (1.32) (0.16) (0.48) -1.29*** -1.12 -1.41 (-3.92) (-1.19) (-1.47) -0.21 -0.23 -0.38 (-0.42) (-0.16) (-0.27) 2.51** 2.12 2.59* (5.36) (1.61) (1.93) 0.64 0.78 0.58 0.78 0.61 94.14 34.74 24.05 33.70 18.22 31.95 (0.0000) 25.42 (0.0000) 728 728 728 728 728 56 7 56 7 56 7 Note: *, **, *** indicate significance at 10, 5 and 1 per cent respectively -t-statistics in parentheses 15 56 7 56 7 The Table shows that all the estimated coefficients of the preferred model in column 6 carry their expected signs, and in line with the theory, except the dummy variable of common language and ex-colony links. The coefficient of GDP of reporter country is positive and significant as expected, implying that an increase in national income of the exporter country encourages trade flow to the trading partner. The impact of reporter’s population is also positive and significant, confirming most of the previous empirical studies (e.g. Simwaka (2011) and Pastore et al. (2009)). The GDP and population size of the trading partner have positive impact on trade flow from the source countries. This finding indicates that a trading partner with large economy and market size measured by its GDP and population size exerts positive effect on the volume of trade with the reporter country. In addition, the coefficient of geographical distance is negative as expected, implying that high transportation cost between member countries negatively affect trade flow. Unexpected, the coefficient of the dummy variable of common language or common border is negative, but it is not statistically different from zero. This result suggests that members speak same language or have ex-colony links tend to reduce the size of trade between them. This finding could be explained by the fact that there is few countries in ASEAN speak the same language and most of them are occupied by different colonizers. Finally, the impact of common border is found to be positive, suggesting that members sharing a common land or sea borders enjoy more trade activities between them. 5.2. Estimating Potential Trade of COMESA Integration Having estimated the gravity model of ASEAN members, the next step is to project the potential trade by applying the coefficients of the gravity model in column 6 of Table 3 to a sample of eight COMESA countries, over the period 2004-2011. We excluded the coefficient of common language or colony links, because it is not consistent, nor is statistically significant. Thereafter, the potential trade will be compared with actual trade in order to assess the success of intra-COMESA trade. The ratios of potential to actual trade between each of eight COMESA members and other partner are presented in Figure 16 1 through 8 in Annex V. Since our sample involves eight countries, each of them has seven country pairs which presented in seven graphs. Figures 1 to 8 show that the ratio of potential to actual trade is greater than one, implying that potential trade among these eight COMESA members is higher than actual trade level. Though, a big difference between observed and predicted level of trade for all trading members, there is a variation across countries. Figure 1 reveal that the actual trade of Egypt with all trade partners is far from its potential, over the period 2004-2011. The ratio of potential to actual trade exceeds more than one thousand for three country pairs: Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe. This is referred to the far distance between Egypt and these countries. On the other hand, Egypt has a low potential trade gap with Ethiopia, Kenya and Mauritius. However, for all country pairs the gap between Egyptian potential trade and actual one has been decreased in recent years, As for the performance of Ethiopian regional trade with other selected COMESA members, Figure 2 points out that Ethiopian actual trade with Egypt and Kenya is closer to its potential compared to other countries in the sample. However, in the last decade there is remarkable progress toward decreasing the gap between potential and actual trade with all members, implying that Ethiopia has scope to increase its trade with other COMESA members, benefited from the adoption of FTA in recent decade. Regarding the regional trade performance of Kenya, Figure 3 reveals that Kenya is most successful country among the selected COMESA member states. As shown in Figure 3 the actual trade of Kenya is less distant from its potential with all countries, especially Uganda. Among all countries Kenya-Uganda trade relation is most successful, as the ratio of potential to actual trade is less than 1. This situation is due to the common border, language and ex-colony links between the two countries. Overall, compared to all remaining eight countries, Kenya has a successful regional trade performance within COMESA countries. 17 Figure 4 presents the performance of Malawi regional trade with other selected COMESA countries. Like other members, Malawi is far from its potential with most of the countries. However, with some countries like Egypt, Zambia and Zimbabwe, the Malawian trade undergone improvement in last five years. This is referred to the closeness of Zambia and Zimbabwe beside the huge economy of Egypt. The similar results are reported for Mauritius in Figure 5. The Figure show that Mauritius’ trade is also far from its potential with other countries during the period 2004-2011. With some countries like Kenya, Zambia and Zimbabwe, the actual trade of Mauritius is somehow close to its potential. As for Ugandan regional trade performance, Figure 6 indicates that with most of the country pairs in the sample the actual trade of Uganda is more distant from its potential. Nevertheless, Uganda is closer to its potential with Kenya, supporting the results in the Kenyan case. Also the results of Zambia and Zimbabwe trade potential in Figure 7 and 8 indicate that their potential trade is far from the actual trade for all selected COMESA members, except the neighbouring countries. The figures show that the ratio of potential to actual trade for Zambia-Zimbabwe and Zimbabwe-Zambia is close to one. On the other hand, for non neighbouring countries, the ratio of potential/actual trade is very high, reported more than thousand for some far distant countries such as, Ethiopia and Uganda. This finding suggests that distance and transport costs have a negative impact on intraCOMESA trade performance. Overall, all selected COMESA countries are far from their potential trade level, although some countries like Egypt, Kenya and Ethiopia experienced a developed performance of trade integration. Only Kenya-Uganda trade relation is the most successful country pair in selected COMESA members, confirming the significant impact of common language, borders and ex-colony links on regional trade. However, all country pairs have undergone a decreasing trend of the ratio of potential to actual trade in last ten years, implying that the adoption of FTA has result in removing trade barriers between the COMESA member states. 18 6. Conclusion and Policy Implications This paper aims at assessing the performance of intra-COMESA regional integration on the basis of success of ASEAN trade integration, using an out-of-sample approach. The analysis used a gravity model for a sample of ASEAN countries over the period 19982010. The estimated coefficients of the gravity equation were applied to intra-COMESA trade model to calculate the potential trade. Then, the performance of intra-COMESA trade integration is measured by the ratio of potential to actual trade. The empirical results show that the actual trade between most of the country pairs is too far from the estimated potential trade level, implying unfavorable performance of intraCOMESA trade compared to ASEAN trade integration. However, the ratio of potential to actual trade has a downward trend for most of country pairs, suggesting a decreasing difference between actual and potential trade over time. This result also indicates that there is some progress towards the potential trade, indicating the success of implementation of COMESA FTA in last decade. The results also show that actual trade for some relatively developed courtiers like Egypt and Kenya is close to its potential, especially Kenya which is found to be the most effective member in the sample. Moreover, Kenya-Uganda pair has been found as most successful bilateral trade integration among the COMESA members. Further, the results point out that the actual bilateral trade between countries with common language, border or ex-colony links is close to its potential level. This finding confirms the significant impact of distance and cultural aspects on trade among COMESA members. Based on the above findings, many policy implications can be drawn. As COMESA regional cooperation is far from its potential integration level, policy makers in member countries should adopt effective trade promotion measures to achieve trade potential level. The downward trend of potential/actual trade ratio also means a progress toward full trade cooperation which needs further actions to speed the economic and trade integration process. 19 Precisely, exports diversification should be at the top of policy agenda for COMESA countries. Therefore, member countries need to give special attention to industrialization so as to enhance trade integration, since industrialization is the major reason behind the success of ASEAN integration. In addition, increasing regional trade needs promoting transport and communication infrastructure networks between the members. Further efforts should be exerted for attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) as well as promoting the trade sectors. Finally, as COMESA future plans are to implement an economic union, member countries should adopt comprehensive trade liberalization measures ranging from removing tariff barriers to improve customs ports procedures at the borders. References Al-Atrash, H. and Yousef, T. (2000), “Intra-Arab Trade: Is it Too Little?”, IMF Working Paper, No. 10. Anderson, J. (1979), “A Theoretical Foundation for the Gravity Equation”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 9, No. 1. ASEAN Secretariat (2013), About ASEAN, available online at: http://www.asean.org/news/asean-secretariat-news Balassa, B. (1961), The Theory of Economic Integration, Richard Irwin, Homewood (Ill.). Chauvin, S. and Gaulier, G. (2002), “Regional Trade Integration in Southern Africa”, CEPPI, Working paper No. 12. COMESA Profile (2013): available: www.comesa.int COMESA statistics database (COMSTAT) (2013). http://comstat.comesa.int/Home.aspx 20 Egger, P (2000), “A Note on the Proper Econometric Specification of the Gravity Equation”, Economic Letters, 66, 25-31. IMF (2013) World Economic Outlook Khandelwal, P. (2004) “COMESA and SADC: Prospects and Challenges for Regional Trade Integration”, IMF Working Paper, No. 227. Linnemann, H. (1966), An Econometric Study of International Trade Flows. Amsterdam: North-Holland. Markheim, D. (1994) “A note on Predicting the Trade Effects of Economic Integration and other Preferential Trade Agreements: An Assessment”, Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 32, No.1. Oyejide, A., Elbadawi, I and Yeo, S. (1999), Regional Integration and Trade Liberalization in Sub-Saharan Africa, Vol. 3, Regional Case Studies (London: Macmillan Press). Pastore, F., Ferragina, A. and Giovannetti, G. (2009) “A Tale of Parallel Integration Processes: A Gravity Analysis of EU Trade with Mediterranean and Central and Eastern European Countries”, Review of Middle East Economics and Finance 5 (2). Simwaka, K. (2011), “An Empirical Evaluation of Trade Potential in Southern African”, AERC Research Paper, No. 235. African Economic Research Consortium, Nairobi. Stack, M. and Pentecost, E. (2011) “Trade Integration A Gravity Model Approach to Estimating Prospective Trade Gains in the EU Accession and Associated Countries”, Nottingham University Discussion Paper No. 2010/11. 21 Tinbergen, J. (1962), Shaping the World Economy-Suggestions for an International Economic Policy. New York: The Twentieth Century Fund. UNCTAD, (various issues), available online at: http://unctad.org/en/Pages/Statistics.aspx World Bank’ Development indicators, (various issues). 22 Annexes Annex I: The share of COMESA and ASEAN in World Exports: 2000-2010 REGION 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Average COMESA 0.02 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06 0.03 ASEAN 1.54 1.41 1.43 1.56 1.55 1.58 1.58 1.55 1.56 1.59 1.73 1.55 Sources: UNCTAD Statistics and IMF Direction of Trade CD-ROM. Annex II: List of Countries Considered for the Study ASEAN Members Brunei Darussalam Indonesia Laos Malaysia Philippines Singapore Thailand Vietnam COMESA Members Egypt Ethiopia Kenya Malawi Mauritius Uganda Zambia Zimbabwe Annex III: Descriptive Statistics of the Variables Used in the Analysis- ASEAN Integration Variable Trade Mean SD Skewness Kurtosis Normality Observations 19.047 5.548 -2.135 7.464 157.75 (0.000) 728 Reporter’ GDP 24.733 1.581 -0.897 2.659 101.30 (0.000) 728 Partner’ GDP 24.680 1.630 -0.846 2.483 94.94 (0.000) 728 Reporter’ population 16.792 1.979 -0.767 2.527 78.30 (0.000) 728 Partner’ population 16.713 1.985 -0.660 2.385 64.34 (0.000) 728 Annex IV: Descriptive Statistics of the Variables Used in the Analysis- COMESA Variable Trade Reporter’ GDP Partner’ GDP Mean 16.084 23.401 23.196 SD 2.403 1.081 0.763 Skewness -0.440 0.925 0.447 Kurtosis 2.627 3.362 3.686 Jarque-Bera 17.043(0.000) 66.24 (0.000) 23.69 (0.000) Observations 447 447 447 Reporter’ population Partner’ population 16.779 16.792 1.253 1.2649 -0.939 -0.915 3.241 3.205 66.84 (0.000) 63.21 (0.000) 447 447 23 Annex V: Intra-COMESA-Potential Trade/Actual Trade (2004-2011) Figure 1: Egypt-COMESA: Potential Trade/Actual Trade (2004-2011) Ethiopia Kenya Potential Trade /Actual Trade 300 200 100 0 60 40 20 0 Malawi Mauritius 6000 4000 2000 0 300 200 100 0 Uganda Zambia 1500 3000 2000 1000 0 1000 500 0 Zimbabwe 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 24 Figure 2: Ethiopia- COMESA: Potential Trade/Actual Trade (2004-2011) Kenya Egypt 400 300 200 100 0 400 300 200 100 0 Potential Trade /Actual Trade Malawi 6000 Mauritius 4000 3000 4000 2000 2000 1000 0 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2005200620072008200920102011 Uganda Zambia 6000 6000 4000 4000 2000 2000 0 0 Zimbabwe 6000 4000 2000 0 25 Figure 3: Kenya-COMESA: Potential Trade/Actual Trade (2004-2011) Egypt Potential Trade /Actual Trade 8 6 4 2 0 Ethiopia 20 15 10 5 0 Malawi 30 Mauritius 80 60 40 20 0 20 10 0 Zambia Uganda 1.5 15 1 10 0.5 5 0 0 Zimbabwe 300 200 100 0 26 Figure 4: Malawi-COMESA: Potential Trade/Actual Trade (2004-2011) Kenya Egypt 80 60 40 20 0 20 15 10 5 0 Mauritius Ethiopia 800 600 400 200 0 10000 Potential Trade /Actual Trade 5000 0 Zambia Uganda 25 20 15 10 5 0 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 Zimbabwe 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 27 Figure 5: Mauritius-COMESA: Potential Trade/Actual Trade (2004-2011) Egypt Ethiopia 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 1000 800 600 400 200 0 Kenya Potential Trade /Actual Trade 100 Malawi 6000 4000 50 2000 0 0 Uganda Zambia 1500 600 1000 400 500 200 0 0 Zimbabwe 300 200 100 0 28 Figure 6: Uganda-COMESA: Potential Trade/Actual Trade (2004-2011) Ethiopia Egypt 3000 1000 800 600 400 200 0 2000 1000 0 Malawi Kenya 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 Potential Trade /Actual Trade 8 6 4 2 0 Mauritius Zambia 6000 4000 2000 0 1500 1000 500 0 Zimbabwe 6000 4000 2000 0 29 Figure 7: Zambia-COMESA: Potential Trade/Actual Trade (2004-2011) Egypt 300 200 100 0 Ethiopia 2000 1000 0 Potential Trade /Actual Trade Kenya Malawi 40 30 20 10 0 8 6 4 2 0 Mauritius 600 400 200 0 Uganda 1000 500 0 Zimbabwe 6 4 2 0 30 Figure 8: Zimbabwe-COMESA: Potential Trade/Actual Trade (2004-2011) Egypt Ethiopia 1000 6000 4000 500 2000 0 0 Potential Trade /Actual Trade Kenya Malawi 400 300 200 100 0 15 10 5 0 Uganda Mauritius 150 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 100 50 0 Zambia 5 4 3 2 1 0 31