The Gilded Age

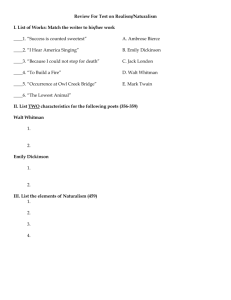

advertisement

Chapter 6 The civil war and the “Gilded Age The Gilded Age Writer and humorist, Mark Twain, wrote the novel The Gilded Age ridiculing Washington D.C. and many of the leading figures of the day Exit Continue Social background The saga of American wealth creation, both for the nation and for its enterprising capitalists, reached its apotheosis during the Gilded Age, a period roughly delimited by the end of Civil War and the beginning of World War I. In America, this period was characterized by seemingly boundless economic expansion and the emergence of a new nation, which had completed the conquest of its vast Western territories and taken the lead among other nations, in industry and trade. America had always been a continent of opportunity, a promising land for the adventurous capitalist as well as for the poor immigrant. Yet, during the Gilded Age, the rapid transformation from an agricultural and mercantile economy to industrialism, presented unprecedented opportunities to daring speculators and inventive entrepreneurs. As the United States economy transformed itself and grew under the leadership of new tycoons, America's established mercantile society once again transformed itself under the impact of the nouveau riches, opportunistic industry leaders or speculative railroad promoters. Exit Continue Walt Whitman (1819-1892) Born on Long Island, New York, Walt Whitman was the son of a poor Quaker farmer-carpenter, and left school at eleven to work as an office boy, first for a law firm and then for a newspaper. Although he had only a few years of formal education he was a rapid and eager reader having read, he later said, almost all of Sir Walter Scott’s novels and much of his poetry before he was twelve. He soon became a typesetter, began contributing short items to his own and other journals. When he was seventeen two big fires temporarily halted the development of the printing industry in Brooklyn and Whitman was forced to return across the bay to his family’s farm. There he made a living by teaching in a country school and angered his father by refusing to help with the farm work after school hours. Five years later, he returned to journalism, he wrote several dull, conventional short stories and some very poor sentimental verse. At that time, he became interested in politics, moving toward abolitionism from support for the Mexican War and a very “moderate” anti-slavery position. Exit Continue Walt Whitman (1819-1892) . In 1842 he went back to Brooklyn and became editor of The New York Aurora. Four years later he assumed editorship of the Brooklyn Eagle, but because of the radical tone of his editorials he did not keep the post for very long. While working for these various newspapers he also began to write poetry and short stories. His early works include a temperance tract, Franklin Evans (1842), written in the form of a novel. In 1848, he traveled south to work on the New Orleans Crescent. The experience of the vastness of the American landscape and the variety of its people made a deep impression on him. He returned to New York later that year and turned his attention increasingly toward poetry. In 1855 he printed the edition of an electrifying book that made up the first edition of Leaves of Grass. The book received little attention, however, it elicit a letter of praise from Ralf Waldo Emerson, which Whitman printed in the second edition (1856). This edition also included 20 new poems, among them “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”. In 1857 he became editor of the Brooklyn Times, his contributions to which were subsequently published in I Sit and Look Out (1932). Exit Continue Walt Whitman (1819-1892) In 1860 he found a publisher for a new poems, including those of the “Calamus” and “ Children of Adam” sections. Whitman was largely self-taught; he left school at the age of 11 to go to work, missing the sort of traditional education that made most American authors respectful imitators of the English. His Leaves of Grass (1855), which he rewrote and revised throughout his life, contains “Song of Myself”, the most stunningly original poem ever written by an American. The enthusiastic praise that Emerson and a few others heaped on this daring volume confirmed Whitman in his poetic vocation, although the book was not a popular success. A visionary book celebrating all creation, Leaves of Grass was inspired largely by Emerson’s writings, especially his essay “The Poet”, which predicted a robust, open-hearted, universal kind of poet uncannily like Whitman himself. The poem’s innovative, unrhymed, free-verse form, open celebration of sexuality, vibrant democratic sensibility, and extreme Romantic assertion that the poet’s self was one with the poem, the universe, and the reader permanently altered the course of American poetry. Exit Continue Walt Whitman (1819-1892) More than any other writer, Whitman invented the myth of democratic America. “The Americans of all nations at any time upon the earth have probably the fullest poetical nature. The United States is essentially the greatest poem.” When Whitman wrote this, he daringly turned upside down the general opinion that America was too brash and new to be poetic. He invented a timeless America of the free imagination, peopled with pioneering spirits of all nations. D.H. Lawrence, the British novelist and poet, accurately called him the poet of the “open road”. Major works Leaves of Grass, Drum-taps (1865) Exit Continue Walt Whitman (1819-1892) The major work of Walt Whitman, the collection consisted of 12 untitled poems when it was first published in 1855. Over the next 37 years it appeared in five revised editions and three reissues. Whitman added, deleted, or revised poems for each edition. Both the form and content of the poems in Leaves of Grass were revolutionary; Whitman’s sprawling lines and cataloguing technique, as well as his belief that poetry should include the lowly, the profane, even the obscene, have had enormous influence. His intention in writing Leaves of Grass, he said, was to create a truly American poem, one “proportionate to our continent, with its powerful races of men, its tremendous historic events, its great oceans, its mountains, and its illimitable prairies.” But the poem goes beyond its specifically American subject to deal with the universal themes of nature, fertility, and mortality. Exit Continue Leaves of Grass is as vast, energetic, and natural as the American continent; it was the epic generations of American critics had been calling for, although they did not recognize it. Movement ripples through “Song of Myself” like restless music: My ties and ballasts leave me... I skirt sierras, my palms cover continents I am afoot with my vision. The poem bulges with myriad concrete sights and sounds. Whitman’s birds are not the conventional “winged spirits” of poetry. His “yellow-crown’d heron comes to the edge of the marsh at night and feeds upon small crabs.” Whitman seems to project himself into everything that he sees or imagines. He is mass man, “Voyaging to every port to dicker and adventure, / Hurrying with the modern crowd as eager and fickle as any.” But he is equally the suffering individual, “The mother of old, condemn’d for a witch, burnt with dry wood, her children gazing on.... I am the hounded slave, I wince at the bite of the dogs.... I am the mash’d fireman with breast-bone broken....” Exit Continue 1 I celebrate myself, And what I assume you shall assume, For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. I loafe and invite my soul, I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass. My tongue, every atom of my blood, formed from this soil, this air, Born here of parents born here from parents the same, and their parents the same, I, now thirty seven years old in perfect health begin, Hoping to cease not till death. Creeds and schools in abeyance, Retiring back a while sufficed at what they are, but never forgotten, I harbor for good or bad, I permit to speak at every hazard, Nature without check with original energy. Exit Continue Song of Myself The celebrated poem by Walt Whitman which introduced the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855. Over 1300 lines long in its final version (1891-1892), it set forth the major themes of Whitman’s early work: the poet’s celebration of the self and of its relation to the common men and women for whom “leaves of grass” is a metaphor; the beauty and spiritual inheritance of the natural world; and the omnipresence and immortality of the cosmic “I” who “ sings” the poem. The poem displays the influence of Emerson’s thought, and Emerson himself hailed it as “ the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed.” It is written in the long, free-verse lines that Whitman used for most of his poetry, and its endless catalogues –“ I will not have a single person slighted or left away. / the kept woman, sponger, thief, are hereby invited” attempt to take up into the poem the multiplicity of American life. Whitman’s voice electrifies even modern readers with his proclamation of the unity and vital force of all creation. He was enormously innovative. From him spring the poem as autobiography, the American Everyman as bard, the reader as creator, and the still-contemporary discovery of “experimental”, or organic form. Exit Continue Song of Myself Three Themes 1. 2. 3. The idea of the self; The identification of the self with other selves; The poet’s relationship with the elements of nature and the universe. Images & Symbols • Houses and rooms represent civilization; • Perfumes signify individual selves; • The atmosphere symbolizes the universal self. The self is conceived of as a spiritual entity which remains relatively permanent in and through the changing flux of ideas and experiences which constitute its conscious life. The self comprises ideas, experiences, psychological states, and spiritual insights. The concept of self is the most significant aspect of Whitman’s mind and art. Exit Continue I hear America singing I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear, Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong, The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam, The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off work, The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deckhand singing on the steamboat deck, The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing as he stands, The wood-cutter's song, the ploughboy's on his way in the morning, or at noon intermission or at sundown, The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work, or of the girl sewing or washing, Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else, Exit Continue The day what belongs to the day--at night the party of young fellows, robust, friendly, Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs. This poem underscores Whitman’s basic attitude toward America, which is part of his ideal of human life. The American nation has based its faith on the creativeness of labor, which Whitman glorifies in this poem. The catalog of craftsmen covers not only the length and breadth of the American continent but also the large and varied field of American achievement. This poem expresses Whitman’s love of America—its vitality, variety, and the massive achievement which is the outcome of the creative endeavor of all its people. It also illustrates Whitman’s technique of using catalogs consisting of a list of people. Exit Continue O Captain! my Captain! O Captain! my Captain! our fearful trip is done, The ship has weather'd every rack, the prize we sought is won, The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting, While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring; But O heart! heart! heart! O the bleeding drops of red, Where on the deck my Captain lies, Fallen cold and dead. O Captain! my Captain! rise up and hear the bells; Rise up- for you the flag is flung- for you the bugle trills, For you bouquets and ribbon'd wreaths- for you the shores a-crowding, For you they call, the swaying mass, their eager faces turning; Exit Continue Here Captain! dear father! This arm beneath your head! It is some dream that on the deck, You've fallen cold and dead. My Captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still, My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will, The ship is anchor'd safe and sound, its voyage closed and done, From fearful trip the victor ship comes in with object won; Exult O shores, and ring O bells! But I with mournful tread, Walk the deck my Captain lies, Fallen cold and dead. Exit Continue Walt Whitman (1819-1892) Influence Through Whitman, American poems finally freed themselves from the old English traditions. He invented a completely new and completely American form of poetic expression. To him, message was always more important than form, and he was the first to explore fully the possibilities of free verse. In his poetry the lines are not usually organized into stanzas; they look more like ordinary sentences. Although he rarely uses rhyme or meter, we can still hear (or feel) a clear rhythm. If you look back over the poems included here, you will find that words or sounds are often repeated. This, along with the content, gives unity to his poetry. Whitman developed his style to suit his message and the audience he hoped to reach. He wrote without the usual poetic ornaments, in a plain style so that ordinary people could read him. He strongly believed that Americans had a special role t o play in the future of mankind. Although he often disapproved of American society, he was certain that the success of American democracy was the key to the future happiness of mankind. Exit Continue Domestic Goddess Harriet Beecher-Stowe is most famous for her controversial anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. Stowe was born in 1811 in Litchfield, Connecticut, the seventh of nine children. Her father was the well-known Congregational minister Lyman Beecher and his wife was Roxana Foote Beecher. Roxana Beecher died when her daughter was five years old, causing Beecher to feel great empathy, she felt, for slave mothers and children who were separated under slavery. As Elizabeth Ammons points out in her preface to the Norton edition, if Beecher had been a man, she probably would have followed in her father's footsteps and become a minister. As it was, she was also wife and sister to preachers. She maintained that it was her Christian passion which compelled her to write her novel. The Stowes' family was not rich, and therefore, Harriet's life was sometimes conflicted between the necessities of motherhood and writing, or, between vocation and avocation. She eventually bore six children, with whom her writing competed. Exit Continue Stowe chose to write Uncle Tom's Cabin because her sister-in-law urged her to use her skills to aid the cause of abolition. The novel was incredibly popular and sold more copies than any book before it, with the exception only of the Christian Bible. "Today, Uncle Tom's Cabin raises many questions. It requires readers to confront and think about racism, and theories of race in the United States. It provokes important questions about differing feminist ideologies and agendas across race and time" (Ammons, intro). Whatever our feelings about the novel, it remains one of the most influential American texts written by either man or woman. It is possibly the first American social protest novel, and anyone concerned with the state of race relations should read it. Critics often denounce the novel for its often sentimental and stereotyped portrayal of its African-American characters, and for romanticizing slavery, but others answer their claims by saying that the critics have not read or completely understood Stowe's intended message and agenda. Whatever your personal feelings about the novel, and Stowe's agenda, it remains an important text for our history. Exit Continue Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) united Northern feelings against slavery. As soon as it was published, it became a great popular success. Hundreds of thousands copies were sold in American before the Civil War: since then it has been translated into over twenty languages and millions of copies have been sold worldwide. It is the story of an old black slave, Uncle Tom, who has the hope of freedom held before him but who never escapes from his slavery. In the end, he welcomed the death caused by his cruel master, Simon Legree. As a masterpiece of Abolitionist propaganda, Exit Continue the book had its effect. It helped expand the campaign in the North against Southern slavery that led to the Civil War. In 1863, when Abraham Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) in Washington, he greeted her with, “so you’re the little woman who made the book that made the great war.” An actual advertisement from 1784 Exit Continue Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) Emily Dickinson was born in 1830 into a Calvinist family of Amherst, Massachusetts. Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, in 1830. She attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley. Emily was an energetic and outgoing woman while attending the Academy and Seminary. It was later, during her midtwenties that Emily began to grow reclusive. In the years that followed, she seldom left her house and visitors were scarce. The people with whom she did come in contact, however, had an intense impact on her thoughts and poetry. She was particularly stirred by the Reverend Charles Wadsworth, whom she met on a trip to Philadelphia. He left for the West Coast shortly after a visit to her home in 1860, and his departure gave rise to a heartsick flow of verse from Dickinson, who deeply admired him. By the 1860s, she lived in almost total physical isolation from the outside world, but actively maintained many correspondences and read widely. Exit Continue Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) She is, in a sense, a link between her era and the literary sensitivities of the turn of the century. She never married, and she led an unconventional life that was outwardly uneventful but was full of inner intensity. She loved nature and found deep inspiration in the birds, animals, plants, and changing seasons of the New England countryside. We find no mention of the war or any other great national event in her poetry. She lived a quiet, very private life in her little hometown of Amherst, Massachusetts. Dickinson spent the latter part of her life as a recluse, due to an extremely sensitive psyche and possibly to make time for writing (for stretches of time she wrote about one poem a day). Her day also included moneymaking for her attorney father, a prominent figure in Amherst who became a member of Congress. Of all the great writers of the nineteenth century, she had the least influence on her times. Yet, because she was cut off from the outside world, she was able to create a very personal and pure kind of poetry. Since her death, her reputation has grown enormously and her poetry is now seen as very modern for its time. Exit Continue Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) Features Dickinson’s terse, frequently imagistic style is even more modern and innovative than Whitman’s. She never uses two words when one will do, and combines concrete things with abstract ideas in an almost proverbial, compressed style. Her best poems have no fat; many mock current sentimentality, and some are even heretical. She sometimes shows a terrifying existential awareness. Like Poe, she explores the dark and hidden part of the mind, dramatizing death and the grave. Yet she also celebrated simple objects -- a flower, a bee. Her poetry exhibits great intelligence and often evokes the agonizing paradox of the limits of the human consciousness trapped in time. She had an excellent sense of humor, and her range of subjects and treatment is amazingly wide. Her poems are generally known by the numbers assigned them in Thomas H. Johnson’s standard edition of 1955. They bristle with odd capitalization and dashes. Exit Continue Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) The subjects of Dickson’s poetry are the traditional ones of love, nature, religion, and mortality, seen through her puritan eyes, or as she described it, “ New Englandly”. Much of the dramatic tension stems from her religious doubt; she was unable to accept the orthodox religious faith of her friends and schoolmates, yet she longed for the comfort and emotional stability that such faith could bring. Many of her lyrics, in their mixture of rebellious and reverent sentiments, illustrate this conflict. Her poetry is also notable for its technical irregularities, which alarmed her early editors and reviewers. Her characteristic stanza is four lines long, and most poems consist of just two stanzas. She often separated her words with dashes, which tend to relieve the density of the poems and introduce into them moments of speculative silence. Other characteristics of her style: sporadic capitalization of nouns; convoluted and ungrammatical phrasing; off- rhymes; broken meters; bold, unconventional, and often startling metaphors; and aphoristic wit, all these have greatly influenced 20th century poets and contributed to Dickson’s reputation as one of the greatest and most innovative poets of 19th century American literature. Exit Continue Major works Poetry Poems by Emily Dickinson (1890) Poems: Second Series (1891) Poems: Third Series (1896) The Single Hound: Poems of a Lifetime (1914) The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson (1924) Further Poems of Emily Dickinson: Withheld from Publication by Her Sister Lavinia (1929) Unpublished Poems of Emily Dickinson (1935) Bolts of Melody: New Poems of Emily Dickinson (1945) The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson (1960) Final Harvest: Emily Dickinson's Poems (1962) Prose Letters of Emily Dickinson (1894) Emily Dickinson Face to Face: Unpublished Letters with Notes and Reminisces (1932) Exit Continue I heard a fly buzz when I died I heard a fly buzz when I died; I willed my keepsakes, signed away The stillness round my form What portion of me I Was like the stillness in the air Could make assignable,—and then Between the heaves of storm. There interposed a fly, The eyes beside had wrung them dry, With blue, uncertain, stumbling buzz, And breaths were gathering sure Between the light and me; For that last onset, when the king And then the windows failed, and then Be witnessed in his power. Exit I could not see to see. Continue I heard a fly buzz when I died The death in this poem is painless, yet the vision of death it presents is horrifying, even gruesome. The appearance of an ordinary, insignificant fly at the climax of a life at first merely startles and disconcerts us. But by the end of the poem, the fly has acquired dreadful meaning. Clearly, the central image is the fly. It makes a literal appearance in three of the four stanzas and is what the speaker experiences in dying. The room is silent except for the fly. The poem describes a lull between "heaves," suggesting that upheaval preceded this moment and that more upheaval will follow. It is a moment of expectation, of waiting. There is "stillness in the air," and the watchers of her dying are silent. And still the only sound is the fly's buzzing. The speaker's tone is calm, even flat; her narrative is concise and factual. "I heard a fly buzz when I died" is one of Emily Dickinson's finest opening lines. It effectively juxtaposes the trivial and the momentous; the movement from one to the other is so swift and so understated and the meaning so significant that the effect is like a blow to an emotional solar plexus (solar plexus: pit of the stomach). Some readers find it misleading because the first clause ("I heard a fly buzz") does not prepare for the second clause ("when I died"). Is the dying woman or are the witnesses misled about death? does the line parallel their experience and so the meaning of the poem? Exit Continue I'm Nobody! Who are you? (260) I'm Nobody! Who are you? Are you--Nobody--too? Then there's a pair of us? Don't tell! they'd advertise--you know! How dreary--to be--Somebody! How public--like a Frog -- To tell one's name--the livelong June– To an admiring Bog! Exit Continue I'm Nobody! Who are you? (260) Dickinson adopts the of a child who is open, naive, and innocent. However, are the questions asked and the final statement made by this poem naive? If they are not, then the poem is because of the discrepancy between the persona's understanding and view and those of Dickinson and the reader. Under the guise of the child's accepting society's values, is Dickinson really rejecting those values? Is Dickinson suggesting that the true somebody is really the nobody? The childspeaker welcomes the person who honestly identifies herself and who has a true identity. These qualities make that person "nobody" in society's eyes. To be "somebody" is to have status in society; society, the majority, excludes or rejects those who lack status or are "nobody"--"they'd banish us" for being nobody. In stanza 2, the child-speaker rejects the role of "somebody" ("How dreary"). The frog comparison depicts "somebody" as self-important and constantly selfpromoting. She also shows the false values of a society (the "admiring bog") which approves the frog-somebody. Does the word "bog" (it means wet, spongy ground) have positive or negatives? What qualities are associated with the sounds a frog makes (croaking)? Exit Continue Mark Twain (1835-1910) Samuel Clemens, better known by his pen name of Mark Twain, grew up in the Mississippi River frontier town of Hannibal, Missouri. Ernest Hemingway’s famous statement that all of American literature comes from one great book, Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, indicates this author’s towering place in the tradition. Twain’s style, based on vigorous, realistic, colloquial American speech, gave American writers a new appreciation of their national voice. Twain was the first major author to come from the interior of the country, and he captured its distinctive, humorous slang and iconoclasm. For Twain and other American writers of the late 19th century, realism was not merely a literary technique: It was a way of speaking truth and exploding wornout conventions. Thus it was profoundly liberating and potentially at odds with society. The most well-known example is Huck Finn, a poor boy who decides to follow the voice of his conscience and help a Negro slave escape to freedom, even though Huck thinks this means that he will be damned to hell for breaking the law. Exit Continue All you need is ignorance and confidence; then success is sure. Everyone is a moon, and has a dark side which he never shows to anybody. The man who does not read good books has no advantage over the man who can't read them. Education consists mainly in what we have unlearned. Of all the animals, man is the only one that is cruel. He is the only one that inflicts pain for the pleasure of doing it. I learned long ago never to say the obvious thing, but leave the obvious thing to commonplace and inexperienced people to say. Let us endeavor so to live that when we come to die even the undertaker will be sorry. When in doubt, tell the truth. Exit Continue Mark Twain (1835-1910) Major works The Gilded Age (1873), The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876), Life on the Mississippi (1883), Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), The Prince and the Pauper(1881) A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court(1889) The Man That Corrupted Hadleydburg (1900), Exit Continue The Celebrated Jumping Frog This collection of stories was Mark Twain’s first published book. The title sketch, which first appeared in the New York Saturday Press in 1865, was based on an old California folk tale. Dan’l Websteer, the champion-jumping frog, is owned by Jim Smiley. A stranger claims that any frog could beat him, and sends Smiley off to catch another one to have a contest. Dan’l is defeated, but only because, as Smiley discovers after the race, the stranger has filled the stomach of the other man’s frog with tiny metal balls. It is a typical Western humor story called a “hoax”. Like all the Western humorists, Twain’s work is filled with stories about how ordinary people trick experts, or how the weak succeed in “hoaxing” the strong. Exit Continue The Gilded Age The Gilded Age written in collaboration with an older writer, Charles Dudley Warner. It sold well and the name, which Twain created, is still often used to describe the corrupt post Civil War period in which and about which, the book was written. Yet neither Twain nor his co-author’s understanding of the age was really adequate, and the collaboration resulted in a rather fragmentary uneven work. The sharply satirized the fraudulent land speculation, dishonest or self-deceiving hopes in get-rich-quick schemes, and above all the public corruption of its era. Congressmen as well as state legislators openly took bribes to vote for bills authorizing the virtual theft of huge tracts of public land and public funds. The Gilded Age also satirized many of the pseudo-romantic popular novels of the time and attacked hypocritical professions of religion, patriotism, or philanthropy. But it moves uneasily from satire to farce, includes chapters of sheer melodrama in the style of the very novels it was mocking, and weakens even its many telling pictures of political corruption by the unrealized basic contradiction in Twain’s own thinking. Exit Continue The Adventure of Tom Sawyer A novel by Mark Twain published in 1876. Tom is an intelligent and imaginative boy, who is nevertheless careless and mischievous. In one of the book’s most famous episodes he is forced to whitewash the frontyard fence as punishment for playing truant. He evades the task by pretending it is a great privilege, and then allowing other boys to take over from him for a considerable price. Tom lives in the respectable home of his Aunt Polly in the Mississippi River town of St Petersburg, Missouri. His preferred world, however, is the outdoor and parentless life of his friend Huck Finn. When Tom is rebuffed by his sweetheart, Becky Thatcher, he and Huck take to the diversion of playing pirates. By coincidence, they are in the graveyard on the night that Indian Joe murders the town doctor and frame the drunkard, Muff Potter, by placing the knife in his hands. Exit Continue The Adventure of Tom Sawyer Tom, Huck, and a third boy hide out on a river island in fear of the half-breed murderer, and are believed dead. They finally return to witness their own passionate eulogies, and with much uproar they are discovered in the funeral audience. Later Tom becomes a hero, when at the trial of Muff Potter he stands up and accuses the true murderer. Joe rushes from the room and thus proves his own guilt. Subsequently Tom and Becky abandon a school picnic and get themselves lost for several days in the very cave where Joe is hiding. They make good their escape, and Tom then returns to cave with Huck. They find Injun Joe dead, and also find his buried treasure. The two boys return to town as heroic as ever, and the riches are divided between them. Exit Continue Huckleberry Finn Twain's masterpiece, which appeared in 1884, is set in the Mississippi River village of St. Petersburg. The son of an alcoholic bum, Huck has just been adopted by a respectable family when his father, in a drunken stupor, threatens to kill him. Fearing for his life, Huck escapes, feigning his own death. He is joined in his escape by another outcast, the slave Jim, whose owner, Miss Watson, is thinking of selling him down the river to the harsher slavery of the Deep South. Huck and Jim float on a raft down the majestic Mississippi, but are sunk by a steamboat, separated, and later reunited. They go through many comical and dangerous shore adventures that show the variety, generosity, and sometimes cruel irrationality of society. In the end, it is discovered that Miss Watson had already freed Jim, and a respectable family is taking care of the wild boy Huck. Exit Continue Huckleberry Finn But Huck grows impatient with civilized society and plans to escape to “the territories” -- Indian lands. The ending gives the reader the counterversion of the classic American success myth: the open road leading to the pristine wilderness, away from the morally corrupting influences of “civilization”. Huckleberry Finn has inspired countless literary interpretations. Clearly, the novel is a story of death, rebirth, and initiation. The escaped slave, Jim, becomes a father figure for Huck; in deciding to save Jim, Huck grows morally beyond the bounds of his slave-owning society. It is Jim’s adventures that initiate Huck into the complexities of human nature and give him moral courage. Exit Continue Life on the Mississippi Originally published in 1883, Life on the Mississippi is Mark Twain’s memoir of his youthful years as a cub pilot on a steamboat paddling up and down the Mississippi River. Twain used his childhood experiences growing up along the Mississippi in a number of works, including The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, but nowhere is the river and the pilot’s life more thoroughly described than in this work. Told with insight, humor, and candor, Life on the Mississippi is an American classic. The unstable relationship between reality and illusion is Twain's characteristic theme, the basis of much of his humor. The magnificent yet deceptive, constantly changing river is also the main feature of his imaginative landscape. Exit Continue Life on the Mississippi In Life on the Mississippi, Twain recalls his training as a young steamboat pilot when he writes: “I went to work now to learn the shape of the river; and of all the eluding and ungraspable objects that ever I tried to get mind or hands on, that was the chief.” Twain’s moral sense as a writer echoes his pilot’s responsibility to steer the ship to safety. Samuel Clemens’s pen name, “Mark Twain”, is the phrase Mississippi boatmen used to signify two fathoms (3.6 meters) of water, the depth needed for a boat’s safe passage. Twain’s serious purpose, combined with a rare genius for humor and style, keep his writing fresh and appealing. Exit Continue A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) is a work of humorous invention set in motion by G. W. Cable, who first brought Malory’s Morte d’Arthur to Mark Twain’s attention. It displays every variety of his style from the mock-heroic and shirt-sleeve journalese of the Yankee’s familiar vein to the careful euphonies of his descriptions of English landscape and the Dantean mordancy of the chapter “In the Queen’s Dungeons.” It exhibits his humour in moods from the grimmest to the gayest, mingling scenes of pathos, terror, and excruciating cruelty with hilarious comic inventions and adventures, which prove their validity for the imagination by abiding in the memory; the sewing-machine worked by the bowing hermit, the mules blushing at the jokes of the pilgrims, the expedition with Alisande, the contests with Merlin, the expedition with King Arthur, Launcelot and the bicycle squad, and the annihilation of the chivalry of England. The hero is, despite the title, no mere Yankee but Mark Twain’s “personal representative”—acquainted with the Exit Continue A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court machine shops of New Haven but acquainted also with navigation on the Mississippi and with Western journalism and with the use of the lariat. The moment that he enters “the holy gloom” of history he becomes, as Mark Twain became when he went to Europe, the representative of democratic America, preaching the gospel of commonsense and practical improvement and liberty and equality and free thought inherited from Franklin, Paine, Jefferson, and Ingersoll. Those to whom Malory’s romance is a sacred book may fairly complain that the exhibition of the Arthurian realm is a brutal and libellous travesty, attributing to the legendary period of Arthur horrors which belong to medieval Spain and Italy. Mark Twain admits the charge. He takes his horrors where he finds them. His wide-sweeping satirical purpose requires a comprehensive display of human ignorance, folly, and iniquity. He must vent the flame of indignation which swept through him whenever he fixed his attention on human history—indignation against removable dirt, ignorance, injustice, and cruelty. As a radical American, he ascribed a great share of these evils to monarchy, aristocracy, and an established church, and he made his contemporary references pointed and painful to English sensibilities. Exit Continue The Prince and the Pauper(1881) "Twain was . . . enough of a genius to build his morality into his books, with humor and wit and—in the case of The Prince and the Pauper—wonderful plotting.“ —E. L. Doctrow Set in sixteenth-century England, Mark Twain's classic "tale for young people of all ages" features two identicallooking boys—a prince and a pauper—who trade clothes and step into each other's lives. While the urchin, Tom Canty, discovers luxury and power, Prince Edward, dressed in rags, roams his kingdom and experiences the cruelties inflicted on the poor by the Tudor monarchy. As Christopher Paul Curtis observes in his Introduction, The Prince and the Pauper is "funny, adventurous, and exciting, yet also chock-full of . . . exquisitely reasoned harangues against society's ills." Exit Continue Topics for discussion 1. 2. Do you find Mark Twain’s description of the friendship between Huck and Jim appealing? Why? How does Huck, a boy with rebellious spirit, come to be a real hero in the reader’s mind? Is his moral travail reasonable? Why? 3. Elaborate on Mark Twain’s use of language in the story. 4. Why do we say The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is a realistic novel? What does Mark Twain convey through the adventures of Huck and Jim on the Mississippi? Exit Continue 1. The Prince and the Pauper is set in sixteenth-century Tudor England during the reign of Henry VIII. This time was marked by a great social and economic disparity between the rich and the poor. How does Twain tackle this issue in the novel? What did you learn from this time period about democracy and monarchy? 2. Some might say Miles Hendon acts as the "hero" in this novel. What heroic qualities does he possess? Is he lacking any that prevent him from being a true hero? 3. What are some of the similarities between Tom's and Edward's lives? What makes the other's life more appealing to Tom and Edward, respectively? How do they grow through their experiences? 4. In the novel, children believe that Edward is the king while the adults do not. Are there other examples where children have greater knowledge than adults? Consider Twain's implications here. 5. The Prince and the Pauper has been compared in style to works of Dickens. What aspect of the novel stands out to you most? Exit Continue