Section 1: Introduction to Macroeconomics

Concepts you’ll learn

1. What “economics” means as a science, and why it’s not a science at all

2. The definition of “money” in economics

3. Government involvement in economics

4. Gross National Product (GNP) and Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

5. The Velocity of Money

6. The Money Multiplier Effect

7. Employment, Unemployment, and Inflation

8. The Business Cycle

9. The Federal Reserve structure and tools of monetary policy

10.Tools of fiscal policy

11.Budget and trade deficits

12.Comparative advantage

Problems you’ll solve

1. Forecast government policy reactions to certain economic developments

2. Forecast the economic impact of government policies

©2014 D. M. Kaufman. All rights reserved

Awright – What’s Economics?

•

Economics is nothing more (or less) than the study of how nations and

individuals manage appetites – needs and wants – for goods and services in

the face of scarce resources

–

•

•

•

“Scarcity” is not the same as “shortage.” Shortages are typically short-term. If a grocery store

runs out of food today, they’ll likely have more tomorrow. Even if the shortage is a longer-lived

crisis; weeks, months, or even years long, it will end. Scarcity, on the other hand, never ends.

There will always be a greater human appetite for goods and services than planet Earth’s resources

can provide.

Macroeconomics focuses on nations’ and governments’ efforts to manage

scarcity.

Microeconomics focuses on individuals’ efforts to manage scarcity.

High level definitions of modern economic systems (there are more than

these three, but they’re the ones you’ll hear and read about the most often

in life)

–

–

–

Capitalism: An economic system based on a free market, open competition, profit motive and

private ownership of the means of production. Capitalism encourages private investment and

business, compared to a government-controlled economy. Investors in these private companies (i.e.

shareholders) also own the firms and are known as capitalists. In such a system, individuals and

firms have the right to own and use wealth to earn income and to sell and purchase labor for wages

with little or no government control. The function of regulating the economy is then achieved mainly

through the operation of market forces where prices and profit dictate where and how resources are

used and allocated. The U.S. is a capitalistic system although, as we’ll see, the U.S. does exercise

some control over its economy.

Socialism: In theory, the government assumes control over all economic decisions. In practice, only

certain aspects of economic activity falls under government control. i.e. In much of Europe, health

care is managed by the government and is provided free of charge to all citizens.

Communism: Communism goes beyond socialism in that, rather than managing one or more

aspects of economic activity (i.e. health care), all or most economic activity is prescribed by the

government and all property and wealth is controlled by the government. In other words, not only

is health care administered by the government, but in some cases an individual can only study to

become a doctor, nurse, or health care administrator if the government says it’s okay. And this

level of control extends to all or most career paths and walks of life.

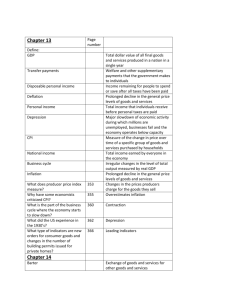

Macroeconomics -- Definitions

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Money: In economics, “money” really refers to “money supply,” which is the entire quantity of bills, coins, loans,

credit and other liquid instruments in a country's economy, and is referred to by its three subcategories – M1, M2,

and M3.

M1: A category of the money supply that includes all physical money such as coins and currency; it also includes

demand deposits (checking accounts). This is used as a measurement for economists trying to quantify the

amount of money in circulation. The M1 is a very liquid measure of the money supply, as it contains cash currency

and assets that can quickly be converted to cash currency.

M2: Includes M1 as well as all time-related deposits, savings deposits, and non-institutional money-market funds.

M2 is a broader classification of money than M1. Economists use M2 when looking to quantify the amount of

money in circulation and trying to explain different economic monetary conditions.

M3: Includes M2 as well as all large time deposits, institutional money-market funds, short-term repurchase

agreements, along with other larger liquid assets. This is the broadest measure of money; it is used by

economists to estimate the entire supply of money within an economy.

Money Velocity: A term used to describe the rate at which money is exchanged from one transaction to another.

Opportunity Cost: The cost of pursuing one course of action measured in terms of the foregone return that could

have been earned on an alternative course of action (more details in Section 4).

GDP: Gross Domestic Product. The monetary value of all the finished goods and services produced within a

country's borders in a specific time period, though GDP is usually calculated on an annual basis. It includes all of

private and public consumption, government outlays, investments and exports less imports that occur within a

defined territory.

GNP: Gross National Product. An economic statistic that includes GDP, plus any income earned by residents from

overseas investments, minus income earned within the domestic economy by overseas residents.

Business Cycle: The recurring and fluctuating levels of economic activity that an economy experiences over a

long period of time. The five stages of the business cycle are growth (expansion), peak, recession (contraction),

trough and recovery. At one time, business cycles were thought to be extremely regular, with predictable

durations, but today they are widely believed to be irregular, varying in frequency, magnitude and duration.

Inflation: The rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, and, consequently,

purchasing power is falling. (You’ll keep hearing about this one as well.)

Full Employment: A situation in which all available labor resources are being used in the most

economically efficient way. Full employment embodies the highest amount of skilled and unskilled labor that could

be employed within an economy at any given time.

Unemployment: The percentage of the total labor force that is unemployed but actively seeking employment and

willing to work.

Fiscal Deficit: When a government's total expenditures exceed the revenue that it generates (excluding money

from borrowings). Deficit differs from debt, which is an accumulation of yearly deficits.

Trade Deficit : An economic measure of a negative balance of trade in which a country's imports exceeds its

exports. A trade deficit represents an outflow of domestic currency to foreign markets.

Comparative Advantage: A situation in which a country, individual, company or region can produce a good at a

lower opportunity cost than a competitor.

The U.S. Government’s Role in the U.S. Economy

• Remember, the U.S. economy is based on

capitalism…

• …but that doesn’t mean the government doesn’t

have a role to play.

• Most simply put, the U.S. government attempts to

do two things:

– Encourage production of what the nation needs most

• The U.S. government can either hire people or encourage business to

produce goods and services which, in the government’s opinion, are in

the best interest of the United States.

– Guide the economy through the business cycle

• The U.S. executive branch and the Federal Reserve both have very

powerful tools available to them which can encourage the economy to

expand or contract, and the rate at which it expands or contracts

Encouraging Production – “Guns and Butter”

•

•

Eh? Guns and Butter? Is that an 80s hair band?

No. It’s an oversimplification of the opportunity costs faced by the government

Production

Possibility Curve

2nd production

possibility curve,

assuming

increased

productivity

•

•

The “Guns and Butter Curve” is the classic economic example of the production

possibility curve, which demonstrates the idea of opportunity cost. In a

theoretical economy with only two goods, a choice must be made between how

much of each good to produce. As an economy produces more guns (military

spending) it must reduce its production of butter (consumer spending), and vice

versa.

In the chart, the solid red curve represents all possible choices of production for

the economy. The black dots represent two possible choices of outputs. The point

here is that every choice has an opportunity cost; you can get more of something

only by giving up something else. Also notice that the curve is the limit to the

production - you cannot produce outside the curve unless there is an increase in

productivity.

GDP, GNP, and the Velocity of Money

• More on GDP

– GDP = C + G + I + NX, where:

"C" is equal to all private consumption, or consumer spending, in a nation's economy

"G" is the sum of government spending

"I" is the sum of all the country's businesses spending on capital

"NX" is the nation's total net exports, calculated as total exports minus total imports.

(NX = Exports - Imports)

– GDP is commonly used as an indicator of the economic health of a country, as well as

to gauge a country's standard of living. A “recession” officially occurs when GDP

contracts for two or more consecutive quarters (that is, six months or more).

• More on GNP

– GNP is another measure of a country's economic performance, or what its citizens

produced (i.e. goods and services) and whether they produced these items within its

borders. Like GDP, GNP is often used as a benchmark for economic health.

• More on Money Velocity

– Velocity is important for measuring the

rate at which money in circulation is

used for purchasing goods and services.

This helps investors gauge how robust

the economy is.

• The faster the money velocity,

the faster GDP and GNP grow

Government

Services

& Income

Services

Taxes

Taxes

Goods, Services,

& Income

Consumers

Businesses

Payments

• Notice anything funny about this? Is higher money velocity always best? Are you sure?

• So, part of this continuum is households making payments to businesses. Are more and higher payments

always better? So it’s best to save nothing? Or to take on debt to spend even more than you earn?

• Funnily enough, economists debate this stuff, and they never agree, because economics is always a

balancing act, and you can seldom be sure of the exact outcome. The “right” amount to save – for one’s

own financial health, for the health of the economy as a whole, etc. – is actually a very complex topic, and

it’s one of thousands upon thousands.

The Money Multiplier Effect

•

•

•

We just saw how money moving more

quickly through the system increases

economic activity. Let’s take a closer

look at another wrinkle…

Touching all parts of the system are

banks and credit markets. These

markets have the powerful ability to

expand an economy’s money supply

through a phenomena called the

“Money Multiplier Effect.”

What Does Multiplier Effect Mean?

Government

Services

& Income

Services

Banks and Taxes

Goods, Services,

Credit

Markets

& Income

Taxes

Households

Businesses

Payments

–

It’s the expansion of a country's money supply that results from banks being able to lend. The size

of the multiplier effect depends on the percentage of deposits that banks are not required to

hold as reserves (i.e. if you deposit $100 in a bank, that bank is not required to keep the entire

$100 on hand – it can use a portion of it to invest or lend in an attempt to earn more money than

they have to pay you in interest). In other words, it is money used to create more money and is

calculated by dividing total bank deposits by the reserve requirement.

–

Example: The formula for the money multiplier is:

To calculate the impact of the multiplier effect on the money supply, we start with the amount

banks initially take in through deposits and divide this by the reserve ratio. If, for example, the

reserve requirement is 20%, for every $100 a customer deposits into a bank, $20 must be kept in

reserve. However, the remaining $80 can be loaned out to other bank customers. This $80 is then

deposited by these customers into another bank, which in turn must also keep 20%, or $16, in

reserve but can lend out the remaining $64. This cycle continues - as more people deposit money

and more banks continue lending it - until finally the $100 initially deposited creates a total of $500

(or $100 divided by 0.2) in deposits. This creation of deposits is the multiplier effect.

The higher the reserve requirement, the tighter the money supply, which results in a lower

multiplier effect for every dollar deposited. The lower the reserve requirement, the larger the money

supply, which means more money is being created for every dollar deposited.

A high velocity of money and a high money multiplier effect can act as dual booster rockets

for the economy, but… balance is still needed (you’ll be hearing “balance” a lot).

More on Balance: Unemployment and Inflation

•

At first blush, you might think that 0% unemployment should be a primary

economic goal, but… think it through…

–

–

•

–

The above phenomenon is called the “Price/Wage Spiral,” and it provides

tremendous fuel for high inflation rates.

–

–

•

If everyone is employed, companies can’t easily grow their workforces. They have to offer higher

and higher wages to entice workers to join them.

Workers then take all that money and bid against each other for the same goods and services,

pushing prices up.

Rising prices then lead workers to demand higher wages, and the cycle begins again.

Remember how inflation works. As inflation rises, every dollar will buy a smaller percentage of a

good. For example, if the inflation rate is 2%, then a $1 pack of gum will cost $1.02 in a year.

Low-to-moderate inflation is expected, but high inflation (sometimes called hyperinflation) rates can

cripple an economy by eroding everyone’s purchasing power and standard of living. Most countries

try to sustain inflation rates of 2% to 3%.

•

So, interestingly enough, some unemployment keeps wages in check, and

therefore helps constrain inflation, but…

What level of unemployment should be the target? That’s another topic

that economists endlessly debate.

Side Note: How high can the inflation rate get?

•

Ah, okay, another side note: how can it get that high?

•

–

–

In the U.S., the oil crisis of the 1970s sent inflation over 10%.

In Zimbabwe in 2008, the inflation rate climbed over 9,000,000%. That’s not a typo.

–

In many countries, including the U.S. each unit of currency used to be backed by an equivalent unit

of gold – referred to as the “gold standard.”

As the world population grew, the gold standard became regarded as a barrier to global economic

growth. Hyperinflation was an impossibility, but a finite amount of money had to be spread ever

more thinly over more and more people and businesses.

In 1971, Richard Nixon took the U.S. off the gold standard. Right move? Guess what? Economists

are still debating it.

–

–

Practical “Balance”: The Business Cycle

•

•

•

Over the long term, the U.S. and

worldwide economies trend

upward (as measured by GDP).

But, they don’t trend up in a

straight line. The fluctuations

make up the business cycle

A wise government will try to

dampen the business cycle – you

don’t want the peaks to be too

high or the troughs to be too

deep. Moderate, steady growth is

the goal.

Peak

Recovery

Trough

– To dampen a peak, money and other

resources need to be withheld from

the economy. This is called “saving

your way off the peak.”

– To dampen a trough, money and resources need to be poured into the economy. This is

called “spending your way out of the trough.”

•

•

We’ve learned this lesson the hard way. Ever heard of the Great

Depression? It was caused in part by the government adopting a stance

of withholding money and resources (a “tight money” policy) after the

economy peaked and started trending downward after the “Roaring 20s.”

The trough was hugely exacerbated. What saved us? The massive

spending required to fund WWII.

Of course, managing the business cycle effectively requires politically

unpopular decisions from time to time. That means we need a decision

making body that is not directly subject to the electoral process.

The U.S. Federal Reserve System

•

The Federal Reserve System (also called the Federal Reserve; informally

The Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. Created in

1913 by the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act (signed by Woodrow

Wilson).

Fed Structure

•

–

The graph to the right provides an overview of this

Fed pyramid. For a little insight into the structure of

the Federal Reserve System, consider a few of the

numbers.

•

•

•

•

•

•

At the top of this pyramid is the Chairman of the Board of

Governors, the one person who runs the show.

Next is the Board of Governors, consisting of 7 folks

(including the Chairman), usually economists by training,

who make the big decisions.

The next layer is occupied by Federal Reserve Banks.

These 37 banks dispersed throughout the country,

include 12 District Banks (Headquartered in Boston, New

York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, St. Louis, San Francisco,

Richmond, Atlanta, Chicago, Minneapolis, Kansas City,

and Dallas), and 25 Branch Banks which interact directly

with commercial banks and are primarily responsible for

carrying out the actions of the Fed.

At the bottom of the pyramid are the economy's

commercial banks, including traditional banks, savings

and loan associations, credit unions, and mutual savings

banks. While the number changes over time from

mergers, closings, new start-ups and the like, the total

number of establishments is in the range of about

20,000.

Federal Open

Market

Committee

1

Chairman

Federal

Advisory

Council

7

Board of

Governors

37

Federal Reserve Banks

20,000

Non-Member Banks

350,000,000

The Public

Beneath the pyramid, the foundation upon which the pyramid is built, is the public, the non-bank public to be precise.

This includes people, businesses, and even government agencies that make use of commercial banking services.

Note the two ovals to the side of the pyramid. Each oval is comprised of 12 members. The 12 residing in the oval labeled

Federal Open Market Committee (or FOMC, the 7 Board Members and 5 rotating heads of the 12 District Banks) are

critical to the Federal Reserve's money-supply control. The 12 occupying the other oval labeled Federal Advisory Council

(comprised of the 12 heads of the District Banks) are not quite as important, but still worth noting since they do advise

the FOMC.

The Fed’s Tools

•

•

•

So, what does the Fed do to affect the economy?

The FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) sets Monetary Policy, or what

actions the Fed will take to control the money supply, which in turn influences

the economy. The FOMC’s decisions are implemented by the 37 member banks

and must be followed by the other ~20,000 non-member banks as a requisite to

staying in business.

The most important actions and tools available to the FOMC are:

–

–

–

Reserve Requirement: Requirement regarding the amount of funds that banks must hold in

reserve against deposits made by their customers. This money must be in the bank's vaults or at

the closest Federal Reserve bank. Changes to the reserve requirement are seldom used by the

FOMC because they cause immediate liquidity problems for banks with low excess reserves.

Recently the Federal reserve requirement has effectively been 10%.

Interest Rates: Higher interest rate make borrowing more expensive, and therefore decrease the

economy’s velocity of money. Lower interest rates have the opposite effect.

• Discount Rate: The interest rate that an eligible depository institution (usually a nonmember bank) is charged to borrow short-term funds directly from a Federal Reserve Bank.

• Federal Funds Rate: The interest rate at which a depository institution lends immediately

available funds (balances at the Federal Reserve) to another depository institution overnight.

This is what news reports are referring to when they talk about the Fed changing interest

rates. In fact, the FOMC sets a target for this rate, but not the actual rate itself (because it is

determined by the open market).

Open Market Operations: The practice by which the Fed buys or sells government securities. If

the Fed buys them, it effectively increases the U.S. money supply. If it sells them, it is effectively

destroying money.

• The Fed is incredibly powerful, but not infallible. Remember the premise that a “tight money” policy

exacerbated the Great Depression? That “tight money” policy was put into effect by… the Fed.

• The effectiveness and wisdom of the Fed’s actions are (huge surprise) endlessly debated by economists, but

its existence as a non-elected entity is generally perceived as a benefit to our economy.

• Interesting, isn’t it, that in order to best serve the people we need a powerful entity that we don’t elect?

But that’s a discussion for a government class…

Fiscal Policy and Fiscal Deficits vs. Surpluses

• The Fed isn’t the only entity with centralized power over

the U.S. economy. Never forget about POTUS (The

President of the United States).

• POTUS is subject to oversight from the legislative

branch (The House and Senate), but can generally set

the tone for what is called Fiscal Policy.

• The most important tools of Fiscal Policy are

government spending and taxation.

• A neutral stance of fiscal policy implies a balanced budget where G = T

(Government spending = Tax revenue). Government spending is fully funded by

tax revenue and overall the budget outcome has a neutral effect on the level of

economic activity.

• An expansionary stance of fiscal policy involves a net increase in government

spending (G > T) through rises in government spending or a fall in taxation

revenue or a combination of the two. This will lead to a larger budget deficit or a

smaller budget surplus than the government previously had, or a deficit if the

government previously had a balanced budget. Expansionary fiscal policy is

usually associated with a budget or fiscal deficit.

• A contractionary fiscal policy (G < T) occurs when net government spending is

reduced either through higher taxation revenue or reduced government spending

or a combination of the two. This would lead to a lower budget deficit or a larger

surplus than the government previously had, or a surplus if the government

previously had a balanced budget. Contractionary fiscal policy is usually

associated with a surplus.

Let’s Look at the Business Cycle Again

•

Ideally, then, what should a

government do to optimize the

business cycle?

–

1

In theory, when GDP gets above the target

trend line, the government should try to

dampen the cycle and create a budget surplus:

•

–

2

•

And when GDP gets below the target trend

line, the government should try to dampen

the trough:

•

•

•

•

Recovery

1

The Fed should buy securities, lower interest

rates, and lower reserve requirements

POTUS should lower taxes and increase spending;

if enough of a surplus has been created during

the previous expansionary time frame, this can

be done without incurring a budget or fiscal deficit.

3

2

5

Trough

–3

And so the cycle goes on…

–

The U.S. Economy is big. Huge. Guiding it is trying to run an aircraft carrier through a tight slalom

course. In high wind. With ice burgs in the way. Besides, economists always debate everything,

right? Exactly who should the policy makers listen to when it’s time to turn the wheel?

For political reasons, fiscal policy and monetary can take very different tacks. In the early 80s, for

example, Reagan cut taxes to increase his popularity while the Fed chairman, Paul Volcker, raised

interest rates through the roof to combat lingering inflation from the oil crisis.

Not to put too fine a point on it, sh*t happens. Things like World War II. Earthquakes. Floods,

Swine Flu. It’s difficult to plan effectively for every contingency.

Great. So what’s so tough about that?

Three major things:

–

–

•

The Fed should sell securities in Open

Market Operations, increase interest

rates, and increase reserve requirements.

POTUS should raise taxes and decrease spending.

4

Peak

Target

Trend

Line

And mistakes can be costly, ranging from hyperinflation

depression 5 .

4

to economic

Final Note on Macroeconomics

• Comparative Advantage and Trade Deficits

– Comparative Advantage

• A situation in which a country, individual, company or region can produce a good at a lower

opportunity cost than a competitor.

• Let's break this down into a simple example. Suppose that two firms both produce two main

products: ice cream and bicycles. The first firm, the Danish Ice Cream and Bicycle Co., is

located in Denmark, where dairy milk is abundant; the second firm, the Gobi Ice Cream and

Bicycle Co., is smack in the middle of the Gobi Desert.

The Gobi Ice Cream and Bicycle Co. must spend a lot of money to make ice cream, whereas

the Danish Ice Cream and Bicycle Co. spends way less to produce the same amount. The two

firms are dead even in their production costs for bicycles.

Because the Danish Ice Cream and Bicycle Co. has a comparative advantage with ice cream

production, it should probably consider turning exclusively to ice cream. Along the same vein,

the Gobi Ice Cream and Bicycle Co. should probably give up the ice cream and focus on the

product in which it is the least disadvantaged (bicycles).

– Trade Deficit

• An economic measure of a negative balance of trade in which a country's imports exceeds its

exports. A trade deficit represents an outflow of domestic currency to foreign markets.

• Economic theory dictates that a trade deficit is not necessarily a bad situation because it often

corrects itself over time. However, a deficit has been reported and growing in the United

States for the past few decades, which has some economists worried. This means that large

amounts of U.S. dollars are being held by foreign nations, which may decide to sell at any

time. A large increase in dollar sales can drive the value of the currency down, making it more

costly to purchase imports.

The law of comparative advantage doesn’t ensure that governments will trade in

their long-term best interests.

Section 1: Practice Problems

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Define GDP. Now, explain it.

Define the Production Possibility Curve. Explain it.

Describe the Velocity of Money’s effect on the economy.

If the federal reserve requirement is 15%, how much

money will be generated in the economy by every $100

deposited in a bank?

If the economy has been growing like gangbusters for

the past year, and POTUS cuts taxes by 50%, would you

call that a good move or a bad move? Why?

If the economy has been in a recession for the past

three quarters, and the Fed sells government securities

in open market operations, would you call that a good

move or a bad move? Why?

If the economy has been in a recession for the past six

quarters, and the Fed cuts interest rates, would you call

that a good move or a bad move? Why?

If you were interested in the current health of the U.S.

economy, can you name a few pieces of data, or

indicators, you’d like to look at? If you can’t, you’d

better re-read this section.