Document

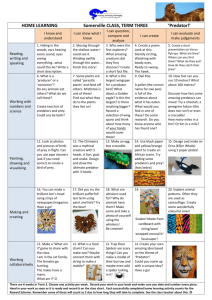

advertisement

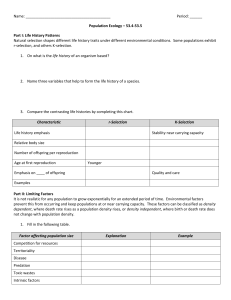

PREDATION • READINGS: FREEMAN Chapter 53 • Students who wish to observe their religious holidays in lieu of attending class must notify Dr. Molumby (molumby@uic.edu). CONSUMPTION • The consuming of one living thing by another. • A basic eating relationship between populations of different species. • Must be evaluated on the basis of its effects on populations, not on individuals. • A + (consumer) / - (consumed) interaction. MAJOR TYPES OF CONSUMPTION • Herbivory --- Eating of plants by animals. May not result in death of individual plant. • Parasitoidism --- Larvae of parasitoids consume hosts. • Cannibalism --- The eater and eaten belong to the same species (intraspecific predation). • Parasitism --- Host provides nutrition to one or many individual parasites. Host may or may not die. • Predation --- Predator kills prey and consumes all or part. HERBIVORY • Occurs when animals eat plants. • Herbivores are those animals that exclusively or primarily eat plant tissue. • Generally restricted to specific parts of the plant (leaves, flowers, fruits, roots, tubers, sap); thus, leaving the rest to regenerate. • Resembles predation when seed (which contains plant embryo), seedling or whole plant is consumed. VERTEBRATE HERBIVORES • Large ungulates are the most conspicuous native herbivores in North America. • Those that feed primarily on grasses and forbs are grazers. Those that feed on tree leaves are browsers. INVERTEBRATE HERBIVORES • Half of all insect species are thought to be herbivores. Groups such as butterflies, moths, weevils, leaf beetles, gall wasps, leaf-mining flies and plant bugs are almost exclusively plant eaters. • Snails, slugs, mites and millipedes are largely herbivores. HERBIVORY Is thought to be ecologically important, but its impact is still debated. Suggested positive impacts include: 1. Increased production and nutrient uptake. 2. Increased quality of leaf litter and soil. 3. Increased chances of successful seedling establishment. 4. Improved conditions for plant growth (pruning effect). Some Evolutionary Responses of Plants to Herbivory • 1. Mechanical forms of protection. Microscopic crystals in tissues, thorns, hooks, spines. • 2. Defensive chemicals. Strychnine, morphine, nicotine, digitoxin, etc. • 3. Fruits. Attractive and tasty tissues surrounding seeds that promote dispersal. PARASITOIDISM • Insects, usually flies and small wasps, that lay their eggs on living hosts. The larvae then feed within the body of the host, eventually causing death. • Recent experimental evidence suggests that parasitoids locate their hosts by responding to airborne chemical signals from plants damaged by the host. PARASITOIDS • A tachinid fly lays eggs on a hornworm (moth larva). The fly larvae develop by consuming the hornworm. • Many species of ichneumon wasps are parasitoids. CANNIBALISM • An individual consumes another individual of the same species. • A form of intraspecific predation. • Relatively common among insects when density is high. Usually involves adults consuming eggs and larvae. • Demonstrated to be density-dependent factor regulating experimental insect populations. PARASITISM • Occurs when a member of one species (parasite) consumes tissues or nutrients of another species (host). • Parasites live on or in their hosts; often for long periods of time. • Parasites are most often much smaller than their hosts. • It is not necessarily fatal to the host. A VERTEBRATE PARASITE • The sea lamprey was introduced into the Great Lakes in 1921 through the Welland Canal. • Contributed greatly to the decline of whitefish and lake trout (shown). • Chemical control programs started in 1956 have reduced lamprey populations. INVERTEBRATE PARASITES • Tapeworm is an intestinal parasite in many species of vertebrates, including humans. • The deer tick (small one) and wood tick are common external parasites on mammals. VIRAL PARASITES • The common influenza virus (top) has inhabited every host in this room! It has caused more deaths than any other pathogen. • The bird flu virus (bottom) is a potential threat to humans. Freeman Figure 52.9 Part 1 QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. Freeman Figure 52.9 Part 2 QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this pi cture. PREDATION • The most conspicuous interaction is when an individual of one species (predator) eats all or most of an individual of another species (prey). • The most thoroughly studied consumptive relationship between species. • Of high ecological and evolutionary significance. • An everyday occurrence in nature. Possible Outcomes of Predation • 1. Predator population has little effect on abundance of prey population. • 2. Predator population eradicates prey population; this may contribute to extinction of predator population due to lack of food. • 3. Predator and prey populations coexist in dynamic equilibrium. A Dynamic Equilibrium Model of Predator/Prey Populations • 1. Assume an exponential growth model for a prey population living in the absence of predators. • 2. Assume an exponential decline model for a predator population living in the absence of prey. • 3. Assume density of predators is a function of density of prey and vice versa. Prey Population Living Alone 18 16 16 14 Number (N) • Assume a constant rate of increase in absence of predators. • dN/dt = r1 N where N = number of prey t = time r1 = reproductive capacity of prey (births exceed deaths) 12 10 8 8 6 4 4 2 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 Time (t) 4 5 Predator Population Living Alone 18 16 16 14 Number (N) • Assume a constant rate of decline in absence of predators. • dP/dt = - r2 P where P = number of predators t = time - r2 = reproductive capacity of predators (deaths exceed births) 12 10 8 8 6 4 4 2 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 Time (t) 4 5 Predator and Prey Populations Living Together • Assume a constant rate of increase in prey population is slowed by an amount depending on the number of predators. dN/dt = (r1 - K1) N ; where K1 = a constant related to the effect of predation on prey. • Assume a constant rate of decrease in predator population is slowed by an amount depending on the number of prey. dP/dt = ( -r2 + K2) P ; where K2 = a constant related to the effect of predation on predators. A Model Predator/Prey Cycle Number of Individuals (N) 250 200 150 P re da to r P re y 100 50 0 0 20 40 60 80 Time (t) This graph shows a limit cycle of predators and prey. Description of Dynamic Equilibrium • When predator numbers are low, prey numbers increase rapidly. • As prey numbers increase, predators begin to increase. • When predators numbers are high, prey numbers decrease rapidly. • As prey numbers decrease, predator numbers fall. The Hare & Lynx Predator/Prey Relationship • Snowshoe hare and Canadian lynx show classic population cycles with a 10-11 year periodicity. • Hare are herbivores and feed on twigs under the snow in winter; lynx feed primarily on snowshoe hare. The Hare/Lynx Cycle Based on Pelt Sales Similar data is provided in Figure 53.10 (Freeman, 2005). Are Hare/Lynx Populations Dynamically Linked? • Evidence For: Lynxes usually have large populations at the same time or just after hares do. Prey abundance often has a dramatic effect on predator abundance. Snowshoe hare abundance has a strong influence on lynx abundance. • Evidence Against: Snowshoe hare populations show cycles on islands where lynxes are absent. Do lynx populations have a strong influence on hare populations? What is the impact of food and predation on the snowshoe hare density?* • Hypothesis: Food or predator or both will influence hare density, thus contributing to the snowshoe hare cycle? • Predictions: 1. Food addition (rabbit chow) will increase hare density. 2. Predator exclusion (enclosure by electric fence that excludes lynxes) will increase hare density. 3. Food addition and predator exclusion will interact to increase hare density. 4. Fertilizer (NPK plant nutrients) addition will stimulate plant growth that will act as hare food and thus increase hare density. *Reported in SCIENCE 8-25-95 What is the impact of food and predation on the snowshoe hare density? • Method: 1 kilometer 2 areas of boreal (coniferous) were managed for 8 years by: 1. Food addition (rabbit chow) 2. Predator exclusion (mammals only, not birds) 3. Food addition and predator exclusion 4. Fertilizer (NPK plant nutrients) addition 5. Control areas (nothing was done in these areas) The 5 different management areas were selected as random from a larger area that had a relatively uniform community structure. Snowshoe hare density was monitored at various periods throughout the 8 year study. What is the impact of food and predation on the snowshoe hare density? • Result: Relative to control areas: 1. Food addition tripled (3x) hare density. 2. Predator exclusion doubled (2X) hare density. 3. Food addition and predator exclusion increased hare density eleven-fold (11X). 4. Fertilizer addition had hare density equivalent to control areas (no effect). • Conclusion: The snowshoe hare population cycles results from: FOOD - HARE - LYNX INTERACTION • Also see: Figure 53.11 in Freeman (2005). He reports the results of the study at the end of 11 years. What Drives the 10-year Cycle of Snowshoe Hares?* I. Food Hypothesis** Test 1. Twig consumption increases as hare density increases, but 60-80% of available food is not consumed. Test 2. Unlimited added rabbit chow does not stop cycle. Test 3. Added natural food does not stop hare decline. * Bioscience 1/01 ** HYPOTHESIS REJECTED What Drives the 10-year Cycle of Snowshoe Hares?* I. Predator Hypothesis** Test 1. 95% of radio-collared hare deaths were due to predation. Test 2. There were few deaths of radiocollared hare where predators were excluded. Test 3. Predator exclusion nearly eliminated the decline phase of the snowshoe hare cycle. * Bioscience 1/01 ** HYPOTHESIS ACCEPTED Moose and Wolf of Isle Royale • The world’s longest running predator/prey research project. The 47th year of wolf and moose monitoring was completed in the winter of 2006. • Winter provides the best opportunities for aerial surveying of the wolf and moose populations, with leaves off the trees and snow on the ground. Moose Population (Early History) • Prior to 1900 there were no moose on the island. • Sometime between then and 1905 a moose population was established. • By 1929, the population was estimated to be around 2,000. • During the early 1930’s the moose destroyed their own food supply and numbers declined. • A fire in 1936 burned browse over a quarter of the island, and by 1937 the moose population was around 400. Many predicted extinction of the population. • The fire stimulated sapling production (browse), so by 1948 the population increased to around 800. Moose Population (Recent History) • First scientific surveys of the moose population began in 1959. • Since that time the population has fluctuated from a low of around 500 to a high of around 2500. Wolf Population • The first wolf tracks on Isle Royale were observed in 1949. • Annual monitoring began in 1959. • Numbers have been as low as 12 and as high as 50. Moose and Wolf Populations of Isle Royale • Significant fluctuations have been observed in both the moose and wolf populations since 1959. • The significant increase in wolf population during the 1970’s corresponds to the decline in moose. Wolves prey on very young, very old, sick or injured moose. • Evidence that wolves impact the moose population is lacking. QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. Predators as Agents of Biocontrol • Predators have been used in attempts to control a variety of plant and animal pests. Often called: biocontrol. • Ladybird beetles and ant lions (lacewing larvae) have been used. Parasites as Agents of Biocontrol • European rabbits were introduced into Australia in 1859 and became a major pest. • In late 1950, the myxoma virus, spread by mosquitoes, began killing rabbits in large numbers. By 1953, rabbit immunity was detected. Today, the virus may kill only 50 % of the rabbit population during an epidemic. • Another virus (calicivirus), native to China, was found and testing as a potential biocontrol agent began in 1995 and continues to the present. PREDATION • READINGS: FREEMAN Chapter 53 • Students who wish to observe their religious holidays in lieu of attending class must notify Dr. Molumby (molumby@uic.edu).