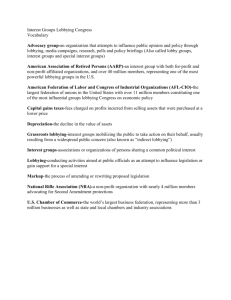

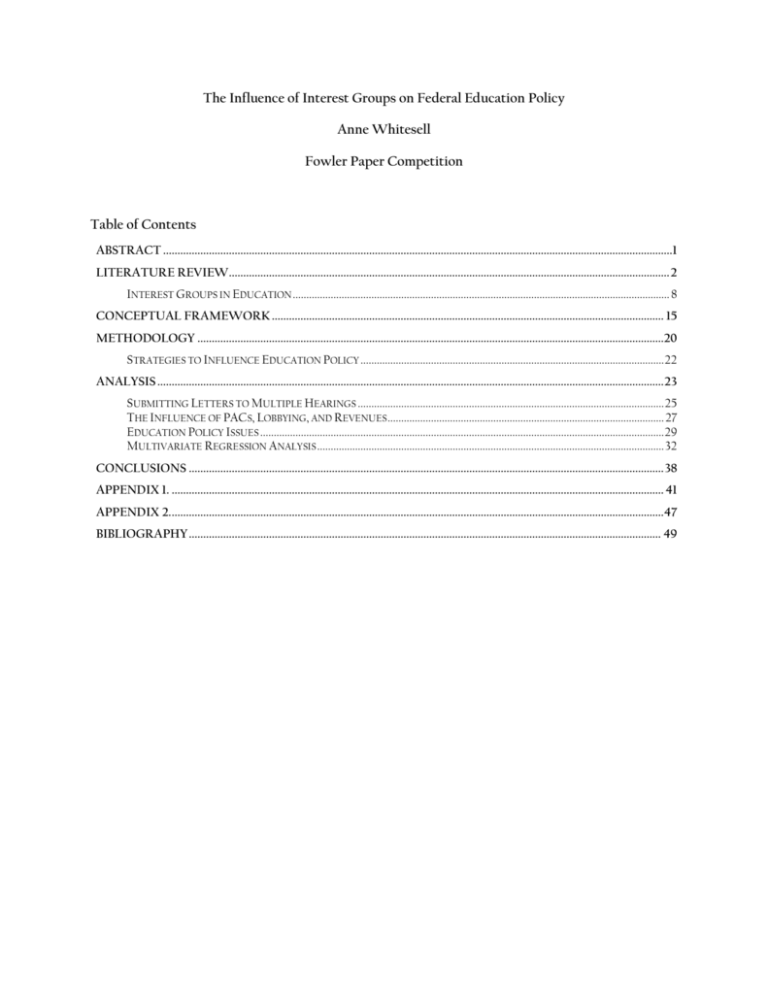

To study the influences of interest groups on

advertisement