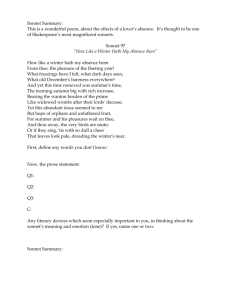

Shakespeare Sonnet Nonfiction Article

advertisement

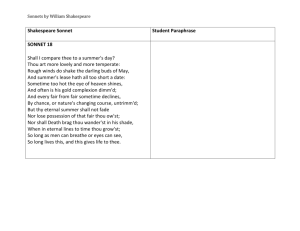

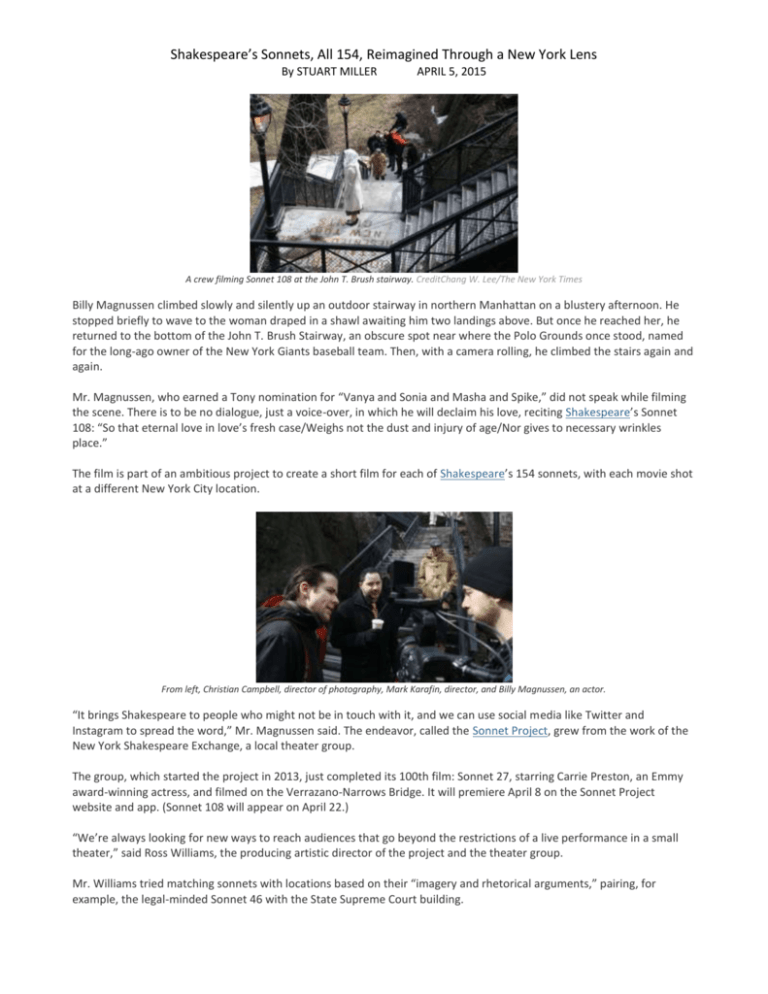

Shakespeare’s Sonnets, All 154, Reimagined Through a New York Lens By STUART MILLER APRIL 5, 2015 A crew filming Sonnet 108 at the John T. Brush stairway. CreditChang W. Lee/The New York Times Billy Magnussen climbed slowly and silently up an outdoor stairway in northern Manhattan on a blustery afternoon. He stopped briefly to wave to the woman draped in a shawl awaiting him two landings above. But once he reached her, he returned to the bottom of the John T. Brush Stairway, an obscure spot near where the Polo Grounds once stood, named for the long-ago owner of the New York Giants baseball team. Then, with a camera rolling, he climbed the stairs again and again. Mr. Magnussen, who earned a Tony nomination for “Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike,” did not speak while filming the scene. There is to be no dialogue, just a voice-over, in which he will declaim his love, reciting Shakespeare’s Sonnet 108: “So that eternal love in love’s fresh case/Weighs not the dust and injury of age/Nor gives to necessary wrinkles place.” The film is part of an ambitious project to create a short film for each of Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets, with each movie shot at a different New York City location. From left, Christian Campbell, director of photography, Mark Karafin, director, and Billy Magnussen, an actor. “It brings Shakespeare to people who might not be in touch with it, and we can use social media like Twitter and Instagram to spread the word,” Mr. Magnussen said. The endeavor, called the Sonnet Project, grew from the work of the New York Shakespeare Exchange, a local theater group. The group, which started the project in 2013, just completed its 100th film: Sonnet 27, starring Carrie Preston, an Emmy award-winning actress, and filmed on the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. It will premiere April 8 on the Sonnet Project website and app. (Sonnet 108 will appear on April 22.) “We’re always looking for new ways to reach audiences that go beyond the restrictions of a live performance in a small theater,” said Ross Williams, the producing artistic director of the project and the theater group. Mr. Williams tried matching sonnets with locations based on their “imagery and rhetorical arguments,” pairing, for example, the legal-minded Sonnet 46 with the State Supreme Court building. He mixed well-known locations, like Grand Central Terminal and the Unisphere, with less familiar ones, like the Holocaust memorial near Madison Square Park. “I wanted a balance so people from out of town had somewhere they could say, ‘I know what that is,’ and others for New Yorkers who might go by these sites every day without realizing it and now they’ll notice them,” Mr. Williams said. Mr. Williams has relied mostly on little-known actors. He has, however, reserved Sonnet 18 — “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day” — and the finale, Sonnet 154, for the most famous names because they will be “calling cards for the project.” (The last sonnet should premiere next spring.) So far, the project’s organizers have spent about $30,000, most if it raised through crowd-funding campaigns. All the actors work at no cost. Mr. Williams hopes to create a walking tour app out of the project. He is also writing a curriculum for high school teachers, to help students learn iambic pentameter, the meaning of the sonnets, and how to make their own films. Some directors found inspiration at the location where the films were shot. At Leidy’s Shore Inn, a 110-year-old bar on Staten Island, Daniel Finley, who was making Sonnet 19, filmed Laurie Birmingham, an actress who works mostly in regional theater, as a world-weary regular musing over her drink. “We walked in at 10 a.m. and the regulars were there watching OTB and scratching their lotto tickets,” he said. “We learned some of their stories and Laurie based her character on those impressions.” At the John T. Brush Stairway, at Edgecombe Avenue near West 157th Street, the director, Mark Karafin, considered incorporating baseball into his film but stuck to the text’s theme “about love being ageless.” While filming Sonnet 116 on the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, Virginia Donohue, who has appeared in a New York Shakespeare Exchange production, spent four hours strolling in the pouring rain with Rich Sommer, an actor familiar to fans of “Mad Men.” She shrugged it off. “The theme is about love’s constancy and the rain was like another obstacle thrown our way so it fit the theme,” she said. Besides: Mr. Sommer happens to be her husband and, she said, “We have small children, so getting a few hours with him away from them is great no matter what.” For Sonnet 13, the director, Ryan Mitchel, faced a different challenge. He and Devin E. Haqq, an actor, wanted to film inside Yankee Stadium while on a tour of it, but their film equipment was not allowed. When they returned a week later, Mr. Mitchel carried a 35-millimeter camera that also records video. “I could film with it but they thought I was just taking photos,” Mr. Mitchel said. Another director, Nicholas Biagetti, tried to film without being noticed after he was unable to get a permit to film Sonnet 50 at Kennedy Airport. He held his camera low to the ground while an actress, Cristina Lippolis, wearing a prosthetic pregnancy belly, lugged a suitcase. Many passers-by seemed to regard Mr. Biagetti as a loutish sort for not carrying her bag. “I got dirty looks,” he said. Ms. Preston and the director, Michael Dunaway, met their share of surprises too, while filming Sonnet 27, about an obsessive love creating a jangle of nerves. Ms. Preston plays a married commuter on her way home, exhausted but excited by a workplace affair. But the drive over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, in a hired car, went smoothly. Too smoothly. “We were hoping for a traffic jam — it’s the perfect metaphor for being stuck in your own mind at the end of a long day — and we filmed at rush hour, but the traffic flowed perfectly,” Ms. Preston said. Ms. Preston said she, Mr. Dunaway, and Karin Hayes, the co-director, went back over the bridge 10 times to get the shots they wanted, running up a much higher than expected bill. “What we forgot about was the toll,” Mr. Dunaway said. “I chalk it all up to the sacrifices we make for art.”