Culture and Social Psychology

advertisement

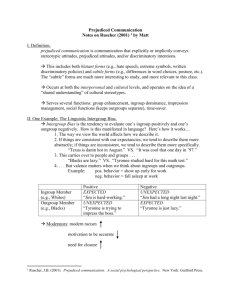

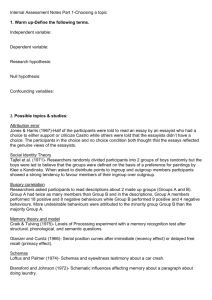

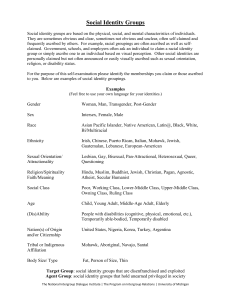

Intergroup Relations Theory and Research: An overview CULTURE AND COOPERATION Cooperation: people’s ability to work together toward common goals Psychologically, human trust and cooperation are based on unique human cognitive abilities (e.g. empathy and concern for others). Cultural differences in cooperation Decisions about cooperation are usually based on specific situational constraints that we encounter, but cultural perspective will invariably apply as well. We are certainly more willing to cooperate with friends and family than with total strangers. But to get a better understanding of the psychology of cooperation we must go beyond mere common sense. What are the relevant theories? What does the research show? How powerful is the role of culture? CULTURE AND INTERGROUP RELATIONS Ingroups and Outgroups A good starting point is group formation itself. Individuals in all cultures make distinctions among the individuals with whom they interact based on group memberships. One type of meaningful social relationship that people of all societies make are ingroups and outgroups Ingroups: Characterized by history of shared experiences and anticipated future interaction. Our ingroups gives a us a sense of intimacy, familiarity, trust and personal security. Ingroups and Outgroups All cultures make ingroup-outgroup differentiation, which leads to psychological consequences. People expect greater similarities between themselves and ingroup and attribute more uniquely human emotions. Cultures ascribe different meanings to ingroup and outgroup relationships. Ingroups and Outgroups Structure and Formation of Ingroup/Outgroup Relationships Cultures differ in formation and structure of self-ingroup and self-outgroup relationships In North American culture, ingroup and outgroup membership is stable, where not true for other cultures (e.g. Zimbabwe) Ingroups and Outgroups The meaning of Ingroup/Outgroup Relationships In Individualistic cultures, people Have more ingroups Are not attached to any single group Survival of individual and society more dependent on individual interests Make less distinctions between in- and outgroups In Collectivistic cultures, people Have fewer ingroups Are very attached to the ingroups to which they belong Survival of individual and society more dependent on group interests Make large distinctions between in- and outgroups Ingroups and Outgroups The meaning of Ingroup/Outgroup Relationships Differences in meaning of ingroup relationships have consequences for behavior Self-outgroup relationships also differ My Own Research: Cross-Cultural Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations Research Questions What are the conditions which force groups to Cooperate with one another? What are the conditions which force groups to compete with on another? Classic work by Sherif and his associates attributed intergroup competition to negatively interdependent goals, i.e., competition for a valued but limited resource. What does this mean? A valued resource can be obtained by one group only at the expense of another group. This causes conflict between groups On the flip side you have positive interdependence in which case a valued but limited resource can be obtained only by working together (cooperating) with one or more groups. This decreases intergroup conflict. From this perspective, group self interest is the primary motivator in group relations The lingering question is : Can there be intergroup cooperation or competition when there is no valued but limited resource at stake? This question was answered by the work of Tajfel and his students by proposing and empirically supporting Social Identity Theory (SIT).. According to SIT, any social categorization which creates identifiable, distinct social groups is enough to evoke in-group bias (favoring one’s own group). Tajfel and associates used the so called minimal group paradigm to support SIT. Competition in the absence of a tangible resource or goal in called social competition. To summarize, according to SIT, mere awareness of membership in a distinct social category is sufficient to evoke in-group bias. These spontaneously generated biases in attitudes and behavior stem from our inherent tendency to achieve positively valued distinctiveness favoring our own group. My own research pushed to envelope by employing naturally occurring groups within a classic experimental paradigm. We selected two ethnic groups which varied significantly in status disparity. One group, Anglos (mainstream Americans), enjoyed Majority Status, whereas the other group, Hispanics, represented a Minority Status social group. The other variable of interest was numeric representation within an intergroup context. In our first study, we used a four person group set-up and either pitted one Angle against three Hispanics (Hispanic Majority) or one Hispanic against three Anglos (Anglo Majority) Physical Set-Up Subjects were seated around a table with partitions to prevent verbal interaction. Each subject compartment contained a controller-like device with a small led screen and two keys, one marked “individual”, the other “group”. The LED screen displayed a number from 1 to 3, representing how many of the other subjects responded “group” after each trial. Pay Off Matrix Placed in from of each subject was a pay-off matrix with numbers representing points they would earn for choosing “individual” or “group” The pay-off varied as a function of how many of the subject picked “group” The pay-off increased for every one with the number of subjects choosing “group”. A subject responding “individual” earned more points than the other subjects for a given trial but, in the long run, would end up with less total points than if he or she had chosen “group”. Hence, the individual response strategy maximized the point difference between a subjects and the others BUT resulted in less total points. The group response resulted in more overall points for the subjects as well as for others. – Greater Absolute Gains. Hence, one strategy would result in less total points for you But even less for the others. The other strategy would increase your overall points BUT also the point totals for the others. Of course, the feedback given after each trail regarding the number of Subject choosing “group” was manipulated to create a “competitive” or “cooperative” intergroup context. What did we find? A Follow-UP Study Questions left unanswered Because the numeric minority condition had had only one subject, we could not conclude if the findings had to do with the “solo” effect (me versus them) as opposed to true intergroup relations effect (us versus them). Also, in the initial study the feedback (cooperative vs. competitive) was a within subjects manipulation. This meant that subjects were exposed to both conditions. Even with half getting “cooperative” first and half “competitive” first, we could not rule out carry over effects. To answered these questions, in the follow-up study, we extended the number of subjects in each group from four to six and place subjects in all possible in-group vs. out-group numeric ratios, ranging from 1 out of 6 to 6 out of six for both Anglo and Hispanic subjects. What did we find?