Prepared by Casey Kalber and Christina McCree on 2/22/2012

advertisement

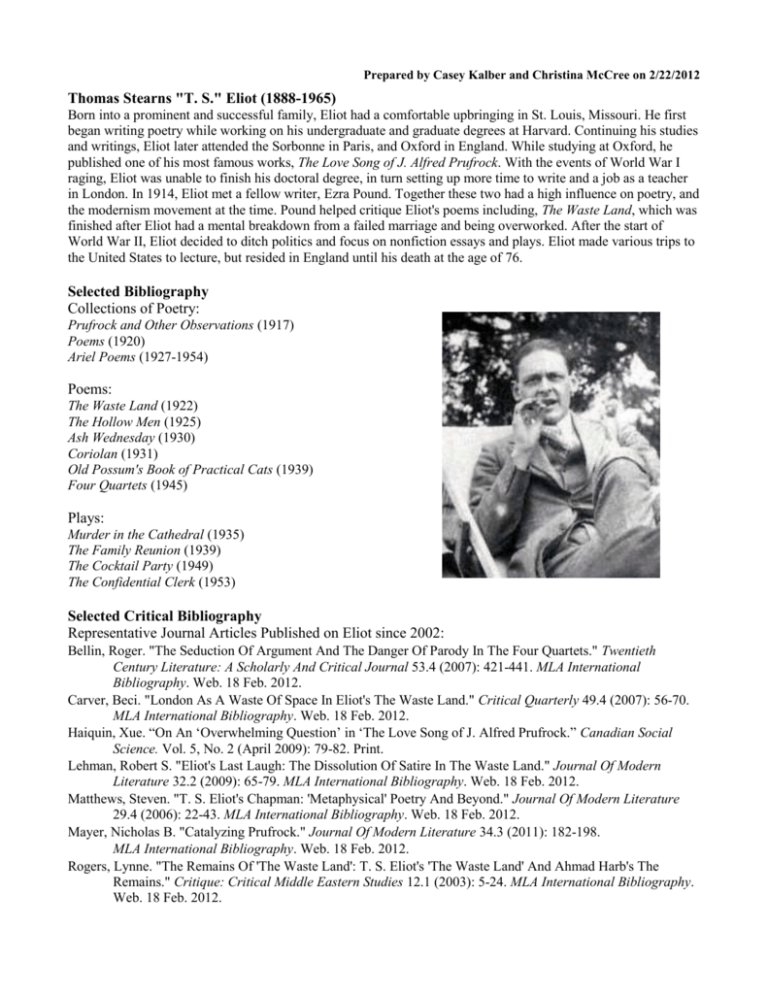

Prepared by Casey Kalber and Christina McCree on 2/22/2012 Thomas Stearns "T. S." Eliot (1888-1965) Born into a prominent and successful family, Eliot had a comfortable upbringing in St. Louis, Missouri. He first began writing poetry while working on his undergraduate and graduate degrees at Harvard. Continuing his studies and writings, Eliot later attended the Sorbonne in Paris, and Oxford in England. While studying at Oxford, he published one of his most famous works, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. With the events of World War I raging, Eliot was unable to finish his doctoral degree, in turn setting up more time to write and a job as a teacher in London. In 1914, Eliot met a fellow writer, Ezra Pound. Together these two had a high influence on poetry, and the modernism movement at the time. Pound helped critique Eliot's poems including, The Waste Land, which was finished after Eliot had a mental breakdown from a failed marriage and being overworked. After the start of World War II, Eliot decided to ditch politics and focus on nonfiction essays and plays. Eliot made various trips to the United States to lecture, but resided in England until his death at the age of 76. Selected Bibliography Collections of Poetry: Prufrock and Other Observations (1917) Poems (1920) Ariel Poems (1927-1954) Poems: The Waste Land (1922) The Hollow Men (1925) Ash Wednesday (1930) Coriolan (1931) Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats (1939) Four Quartets (1945) Plays: Murder in the Cathedral (1935) The Family Reunion (1939) The Cocktail Party (1949) The Confidential Clerk (1953) Selected Critical Bibliography Representative Journal Articles Published on Eliot since 2002: Bellin, Roger. "The Seduction Of Argument And The Danger Of Parody In The Four Quartets." Twentieth Century Literature: A Scholarly And Critical Journal 53.4 (2007): 421-441. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 18 Feb. 2012. Carver, Beci. "London As A Waste Of Space In Eliot's The Waste Land." Critical Quarterly 49.4 (2007): 56-70. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 18 Feb. 2012. Haiquin, Xue. “On An ‘Overwhelming Question’ in ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Canadian Social Science. Vol. 5, No. 2 (April 2009): 79-82. Print. Lehman, Robert S. "Eliot's Last Laugh: The Dissolution Of Satire In The Waste Land." Journal Of Modern Literature 32.2 (2009): 65-79. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 18 Feb. 2012. Matthews, Steven. "T. S. Eliot's Chapman: 'Metaphysical' Poetry And Beyond." Journal Of Modern Literature 29.4 (2006): 22-43. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 18 Feb. 2012. Mayer, Nicholas B. "Catalyzing Prufrock." Journal Of Modern Literature 34.3 (2011): 182-198. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 18 Feb. 2012. Rogers, Lynne. "The Remains Of 'The Waste Land': T. S. Eliot's 'The Waste Land' And Ahmad Harb's The Remains." Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies 12.1 (2003): 5-24. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 18 Feb. 2012. A Review of Xue Haiquin’s “On An ‘Overwhelming Question’ in ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Canadian Social Science Vol. 5, No. 2 (April 2009) p. 79-82. In her essay “On An ‘Overwhelming Question’,” Haiquin explores T.S Eliot’s images and allusions for implying the “question.” She analyzes the meanings of many of Eliot’s references to scenery, literature, and religion in relation to the seemingly doomed character. Although “Prufrock” is a more light-hearted piece than “The Waste Land,” it should be read with the same analytical state of mind to catch Eliot’s witty commentary. First, Haiquin addresses the use of images for implying the question. In the beginning of the poem, Prufrock starts with, “Let us go, you and I,/When the evening is spread out against the sky/Like a patient etherized upon a table…” (lines 1-3). As many critics have pointed out, “you” and “I” are not two different people, but rather two states of mind (80). The “you” is the thinking self, while the “I” is the public personality that is seen the most. “You” is therefore Prufrock’s true self. Also, the evening images are used to imply that the world is passively covered in darkness and that it is difficult for most people to distinguish their true selves while under a mask. Eliot continues to use weather images in the third stanza. The “yellow smoke” usually covers up something, just as fog would, so Prufrock thinks that there will be time “to prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;/There will be time to murder and create…” (lines 26-27). He is so self-conscious and indecisive that he needs time to prepare a false version of himself before the party. Next, Haiquin analyzes Eliot’s use of literary characters and religious figures. The epigraph before the first stanza comes the Inferno of Dante’s “Divine Comedy.” Guido da Montefeltro identifies himself to Dante, basing his self-revelation that no one will discover his identity. Here, Eliot alludes Montefeltro to Prufrock; the difference between them is that Montefeltro dares to reveal to reveal his true identity while Prufrock is afraid to. Also, Eliot compares Prufrock to Hamlet from the Shakespeare play. Hamlet is famous for his hesitancy, indecision, and drawn out dialogues of anxiety, doubt, or unhappiness (81). Prufrock is a sort of modern Hamlet, because he is also very indecisive. Still, he claims he is not the same as the prince, because he is not as noble. Finally, the religious figures that are alluded to are John the Baptist and Lazarus. These two characters, when Prufrock speaks of them, are used to form a vivid contrast or comparison with him. He is neither a prophet, nor a great sage, but merely a “perplexed, unheroic, inhibited, twentieth-century young man” (81). In conclusion, Haiquin declares that the reason for all of the allusions is to make a point: Prufrock is divided into two selves. One wants him to ask the “overwhelming question,” while the other tries to prevent it (82). By writing this poem, Eliot attempted to shed light on the predicament of people in the modern world: a battle within themselves.