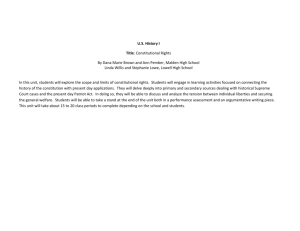

Constitutional Rights unit pilot August 2013

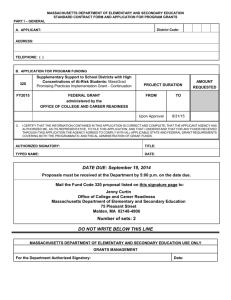

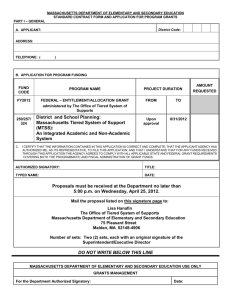

advertisement