lec.4

advertisement

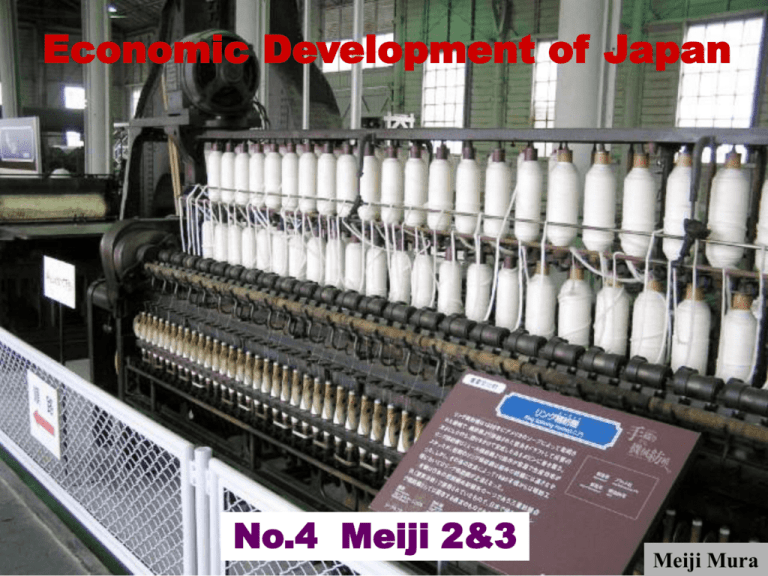

Economic Development of Japan No.4 Meiji 2&3 Meiji Mura P.56 Cumulative history, Edo achievements, national unity and nationalism Japan’s economic growth was driven mainly by private dynamism while policy was also helpful Private-sector dynamism and entrepreneurship (primary force) Policy support (supplementary) Rapid industrialization esp. Meiji and post WW2 period Policy was generally successful despite criticisms: --Power monopoly by former Satsuma & Choshu politicians --Privatization scandal, 1881 --Excessively pro-West --Unfair by today’s standard PP.57-58 Chronology of Meiji Industrialization 1870s - Monetary confusion and inflation US banking system adopted with little success Printing money to suppress Saigo’s Rebellion (1877) Early 1880s - Matsukata Deflation Stopping inflation, creating central bank (Bank of Japan) Landless peasants & urban poor (“proletariat”) emerge Late 1880s - First company boom Masayoshi Matsukata (Councilor of Finance) Osaka Spinning Company and its followers Series of company booms (late 1890s, late 1900s, WW1) Postwar management (after J-China War & J-Russia War) Fiscal spending continued even after war BoP crisis Active infrastructure building (local gov’ts) & military buildup P.230 Inflation in Meiji Period Rice Price per Koku (Yen/150kg) 25000 Matsukata deflation 20000 15000 10000 5000 Source: Management and Coordination Agency, Historical Statistics of Japan, Vol.4, 1988. 1912 1909 1906 1903 1900 1897 1894 1891 1888 1885 1882 1879 1876 1873 0 Money and Inflation in Early Meiji 250 Money i n ci rcul a ti on ( mi l l i on y en) 200 150 R i ce pri ce ( 1868=100) 100 50 Sa i g o's R ebel l i on Ma ts uk a ta def l a ti on 1890 1889 1888 1887 1886 1885 1884 1883 1882 1881 1880 1879 1878 1877 1876 1875 1874 1873 0 First Company Boom 6000 5000 Banking Transport Commerce Industry Agriculture 4000 3000 2000 1000 Legal capital 350 (million yen) 300 1892 1891 1890 1889 1888 1887 1886 1885 0 1884 Number of companies 250 Banking Transport Commerce Industry Agriculture 200 150 100 50 1892 1891 1890 1889 1888 1887 1886 1885 0 1884 Yoshio Ando ed, Databook on Modern Japanese Economic History, 2rd ed, Tokyo Univ. Press, 1979. PP.62-65 Technology Transfer 1. Foreign advisors (public and private sector) 2. Engineering education (studying abroad, Institute of Technology; technical high schools) 3. Copy production, reverse engineering, technical cooperation agreements (esp. automobiles, electrical machinery); sogo shosha (trading companies) often intermediated such cooperation Technical Experts Private-sector experts, 1910 Mining 513 (18.0%) Textile 300 (10.6%) Shipbuilding 250 (8.8%) Power & gas 231 (8.1%) Trading 186 (6.5%) Railroad 149 (5.2%) Food 149 (5.2%) TOTAL 2,843 (100%) (Graduates of Technical Univs. & High Schools) 16000 14000 12000 Private sector Public sector 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 P.64 Studying Abroad (Early Engineers) • First students: bakufu sent 7 students to Netherlands in 1862 (naval training) • By 1880s, 80 Japanese studied engineering abroad (shipbuilding, mechanics, civil engineering, mining & metallurgy, military, chemistry) • Destination: UK (28), US (20), France (14), Germany (9), Netherlands (8) • They received top-class education and could easily replace foreigners after coming back • They mostly worked in government (no modern private industries existed at first)—Ministry of Interior, MoF, Army, Navy, Ministry of Industry Kobu Daigakko 工部大学校 P.64 (Institute of Technology) • 1871 Koburyo of Ministry of Industry; 1877 renamed to Kobu Daigakko; 1886 merged with Tokyo Imperial University (under Ministry of Education) • First President: Henry Dyer (British engineer) with philosophy “judicious combination of theory and practice” • Preparatory course (2 years), specialized studies (2 years), internship (2 years) + government-funded overseas study for top students • 8 courses: civil engineering, mechanical engineering, shipbuilding, telecommunication, chemistry, architecture, metallurgy, mining (classes in English) • Producing top-class engineers (import substitution)—Tanabe Sakuro (designer of Biwako-Kyoto irrigation canal & power generation); Tatsuno Kingo (builder of Tokyo Station, BOJ, Nara Hotel, etc.) Parallel development or “hybrid technology” Manufacturing: Share of Output 100% Indigenous industries 80% 60% Factory size Employment Str uctur e of Pr ewar Japan 100% Indigenous (trade & service) 80% 60% Indigenous (manufacturing) 40% Modern industries 20% Agri, forestry, fishery 1930-35 1925-30 1920-25 1915-20 1910-15 1905-10 1900-05 1895-00 1890-95 1885-90 0% 1935-40 1930-35 1925-30 1920-25 1915-20 * indicates hybrid status 1910-15 M 1905-10 M* 1900-05 Modern 0% 1895-00 I* 20% 1890-95 I Indigenous Modern industries Large 1885-90 Technology Small 40% PP.65-67 PP.79-80 Neoclassical Labor Market Duration of Male Employment in Manufacturing Japanese workers: Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, Survey of Industrial Workers, 1901. 35 30 1902 25 Percent --Too much job hopping, do not stay with one company --Lack of discipline, low saving --Barrier to industrialization 1912 20 15 10 5 0 Female domestic workers: <1 1 2 3-4 5-6 7-9 10> Years --Urban industrialization and rural poverty and labor surplus female migration from villages to cities --End of Meiji to early Showa were the peak period of jochu (housemaid) --17.5% of non-farm female workforce, second largest after textile workers (1930) --5.7% of households hired jochu (1930) --There were both young and old jochu, some living-in and others commuting --International comparison (female non-farm employment share): UK 1851 (11.4%), US 1910 (11.8%), Thailand 1960 (10.6%), Philippines 1975 (34.3%) Source: Konosuke Odaka, “Dual Structure,” 1989. Wage: Gender Gap Farm employment Sen per day Male Female F/M % Textile weavers Sen per day Male Female F/M % Domestic servants Yen per month Male Female F/M % 1885 15.1 9.7 64.2% 12.3 7.5 61.0% 1.38 0.75 54.3% 1892 15.5 9.4 60.6% 12.0 8.4 70.0% 1.55 0.82 52.9% 1895 18.5 11.3 61.1% 18.3 11.6 63.4% 1.64 0.90 54.9% 1900 30.0 19.0 63.3% 33.0 20.0 60.6% 2.70 1.56 57.8% 1905 32.0 20.0 62.5% 34.0 13.0 38.2% 3.22 1.79 55.6% 1910 39.0 24.0 61.5% 49.0 27.0 55.1% 4.56 2.96 64.9% 1915 46.0 29.0 63.0% 46.0 30.0 65.2% 4.97 3.13 63.0% 1920 144.0 92.0 63.9% 175.0 95.0 54.3% 28.86 22.68 78.6% Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, "Table of Wages." Note: 1 yen = 100 sen. Konosuke Odaka: World of Craftsmen, World of Factories (NTT Publishing, 2000) • In Japan’s early factories, traditional shokunin (craftsmen) and modern shokko (workers) coexisted. • Craftsmen were proud, experienced and independent. They were the main force in initial technology absorption. • Workers received scientific education and functioned within an organization. Their skills and knowledge were open, global and expandable. • Over time, craftsmen were replaced by workers. Experience was not enough to deepen industrialization. Prof. Odaka proves these points by examining the history of concrete firms in metallurgy, machinery and shipbuilding. Prof. Odaka’s Working Hypotheses • In the early years of factories, Japan’s traditional craftsmen in mechanics and metal working played key roles in absorbing new technology. Farmers and merchants were not suitable for factory operation. • However, trained engineers, not craftsmen, created a modern production system suitable for Japan. – Adaptation of imported system to Japanese context – Production management system, including hired labor – Skill formation system based on formal education and OJT • The gap between craftsmen’s skill and modern technology had to be bridged. Hired foreigners, then Japanese engineers, provided this bridge up to WW2. PP.65, 179-181 Monozukuri (Manufacturing) Spirit • Mono means “thing” and zukuri (tsukuri) means “making” in indigenous Japanese language. • It describes sincere attitude toward production with pride, skill and dedication. It is a way of pursuing innovation and perfection, often disregarding profit or balance sheet. • Many of Japan’s excellent manufacturing firms were founded by engineers full of monozukuri spirit. Sakichi Toyota 1867-1930 Konosuke Matsushita 1894-1989 Soichiro Honda 1906-1991 Akio Morita (Sony’s co-founder) 1921-1999 Toyota Techno Museum in Nagoya displays textile machines in actual operation, including Sakichi Toyota’s 1924 invention. It also explains Toyota’s car history. www.tcmit.org/english/index.html Meiji Mura (Meiji Village) is an open-air museum of Meiji architecture and culture, Inuyama City, Aichi Prefecture www.meijimura.com/english/index.html