Asexy Story - Warren Wilson Inside Page

A

SEXY

S

TORY

:

Narratives of Negotiating an Asexual Identity

By: Derek Roy

-

Laura Vance

Warren Wilson College

Sociology / Anthropology

A SEXY S TORY

2

A BSTRACT : The prevailing assumption that sexual desire is a fundamental human trait—a position that fundamentally precludes asexuality—has dominated the discourse on sex. In the past several years, asexuality has become known as both a sexual identity and an emerging area of interest in human sexuality. This study draws from the narratives and embodied knowledge of

18 self-identified asexuals from both the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) and the asexual group on LiveJournal (LJ), using semi-structured interviews in order to explore asexual identity formation and negotiation in the context of a variety of relationships, including those with family, friends, romantic partners, communities, and self. Findings indicate that the formation of an asexual identity arises from the elaboration of self narratives that are developed and deployed during a processes encoding and decoding discourses on sex, bodies, sexuality, sexual orientation, and asexuality in a variety of relationships. These experiences equip selfidentified asexuals with a variety of context-specific strategies to disclose this new self-narrative in order to transform previous relationships and develop, multiply, and shape new relationships that are congruent to individual desires. This study suggests a conceptual framework for understanding identity formation and a contextualized understanding of asexual identities and desires.

A SEXY S TORY

3

A SEXY S TORY : N ARRATIVES OF N EGOTIATING AN A SEXUAL I DENTITY

Table of Contents i.

Title Page ...………………………………………………………………………….. 1 ii.

Abstract …...…………………………………………………………………………. 2 iii.

Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………………. 3 iv.

Opening Quote ………………………………………………………………………. 4

I.

Introduction ………………………………………………………………………...... 5

II.

Review of the Literature ……….…………………………………………………..... 5

III.

Theory …………………………………………………………………………….... 12

IV.

Statement of Purpose ……………………………………………………………..... 14

V.

Methods ……………………………………………………………………………. 16

VI.

Results ……………………………………………………………………………... 18 a.

Shades of Grey: Narratives of a Problematized Self b.

Finding Identity: An Exploration of Self, Asexuality, and Community c.

Becoming Asexual: Negotiating Narratives and Constructing an Asexual Identity d.

Am I Asexual?

An Individual’s Process, Identity, & Form-of-Life

VII.

Discussion ………………………………………………………………………….. 41

VIII.

Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………….. 46

IX.

Appendixes ………………………………………………………………………… 50

4

A SEXY S TORY

“

S

EXUALITY IS THE

LYRICISM OF THE

MASSES

”

C

HARLES

P

IERRE

B

AUDELAIRE

A SEXY S TORY

5

I

NTRODUCTION

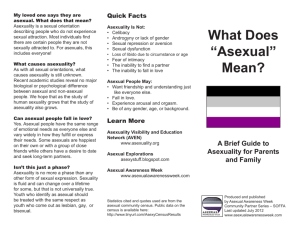

: The prevailing assumption that sexual desire is a fundamental human trait dominates the discourse on sex—a position that fundamentally precludes asexuality. The word asexual, typically used in biology to discuss the reproductive features of invertebrates, has, in the past several years, become known as both a sexual identity and an emerging area of interest in human sexuality. The Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) defines an asexual as “a person who does not experience sexual attraction” (AVEN 2011). This is similar to the definition Bogaert (2004, 2006) uses in their

1

pioneering research on asexuality, which suggests that approximately one percent of the population is asexual, and that asexuality should be considered a unique orientation and not a disorder, according to an eroticism-based definition of sexual orientation. This research employs semi-structured interviews to hear the narratives of self-identified asexuals in order to explore asexual identity formation and negotiation.

R

EVIEW OF THE

L

ITERATURE

: Literature regarding asexuality, outside of the field of biology, remains relatively scarce. Since 2004, only eleven scholarly journal articles have been

1 I use gender-neutral pronoun use through out this paper.

A SEXY S TORY

6 published that specifically explore asexuality in humans. Interestingly, these articles can be divided both thematically—by desire, behavior, and identity (three common ways social scientists conceptualize their interest in sexuality) (Laumann et al. 1994), as well as methodologically—according to disposition, behavior, and self-identification (the three predominate views of orientation) (Stein 1999). I have arranged the literature on asexuality according to these categories, not to reinforce their differentiation, but instead to elaborate upon the limitations of each; the various discourses and disciplines they draw from and contribute to; and the corresponding flows of power, regimes of truth, and apparatuses they maintain.

D ESIRE & D ISPOSITION : The medical and psychological discourses on sexual drives perpetuate the idea of an innate sexual desire, which does not simply dominate the discourse on sexuality, but is also one of its principle assumptions (Foucault 1978). This scientific discourse reiterates what Rubin (1984) describes as sexual essentialism, the assumption that “sex is a natural force that exists prior to social life and shapes institutions” (Scherrer 2008:629). This assumption, in the social sciences—one of many sites where sexuality has become an object of scientific scrutiny—is pivotal to the development of the discourse of ‘sexual orientation’ (Stein

1999). Despite the efforts of the early gay liberationist movement, which often argued that sexuality was fluid and that categories were constructed in order to contain “the erotic potential of human beings,” by the late 1970s most gay activists and academics had begun to employ the more narrow concept of sexual orientation (D’Emilio 2009:449); the idea that a person’s sexual desires are the “result of deep features of a person’s character, perhaps an innate, unchangeable feature” (Stein 1999:41). Duggan and Hunter (1995) explain that this essentializing discourse has

A SEXY S TORY

7 since been useful for gay and lesbian individuals seeking legitimacy and recognition in our society (Scherrer 2008:629).

In addition to the assumption of sexual drives and the norm of sexual desire, also implicit in sexual orientation is a binary division and essentialist conception of gender. From ‘classical theorists of sex, such as Krafft-Ebing (1887), Ellis (1936), Freud (1922), and Tripp (1974)—who defined orientation in relation to one’s sex-role-identity, to the eroticist theorists, such as Kinsey

(1948, 1953) and Storm (1978, 1980), for whom one’s fantasies or attraction toward the sex or gender of another equated one’s orientation—gender binaries have been at the center of each form of sexual desire that constitutes a sexual orientation. A single exception however, is the eroticist approach, which made space conceptually for those whose sexual desire did not have a gender-object choice through the creation of the theoretical ‘asexual orientation’ category.

Ironically, research on asexuality has begun to challenge the concept of sexual orientation as well as the very notion of sexual desire as a universal component of human experience. Like asexuals, who might use the legitimizing effects of asexuality as an orientation, describing asexuality as a ‘unique’ sexual orientation is useful for researchers. Bogaert (2006), for instance, employs an eroticist discourse on orientation that includes an asexual category, to defend their research on asexuality from its critics, who are skeptical of self reporting (and think instead, like

Freud (1991)

2

, that asexuality should be seen as a pathological condition). Models such as

2 Essential to Freud’s theory is the idea that all humans possess groups of primal instincts: the self-preservative or ego-instincts, and the sexual instincts or species-preserving instincts. Freud believed that biology teaches us that

“sexuality is not on a level with the other functions of the individual, for its purposes are beyond the individual, their content being the production of new individuals and the preservation of the species” (1991:78). It is under these assumptions that the Freudian concept of libido, innate sexual desire, is born. The lack of sexual desire thus became

A SEXY S TORY

8

Storms’ (1978), from which Bogaert (2006) draws their eroticism-based gender-object orientation, do not accurately reflect the complexity of many individuals’ asexual identities, since it includes only the forms of eroticism that asexuals ‘lack,’ as oppose to those that they experience.

Recent research on asexuality contests the assumption of an innate sexual desire or arousal that eroticist models of sexual orientation are founded upon. For example, Brotto,

Knudson, Inskip, Rhodes, and Erskine’s (2008) study finds asexuals to be most clearly distinguished from non-asexuals by their lower scores on the Dyadic Sexual Desire subscale, lower scores on the Solitary Sexual Desire subscale, and lower scores on the Sexual Arousability

Inventory—findings which do not support the hypothesis, proposed by Bogaert (2006), that asexual individuals might have some level of sexual desire, arousal, or activity that is “not connected to anyone or thing” (244). Research suggests instead that many individuals that identify as asexual have desires and things that arouse or interest them that are not sexual in nature , such as the ideal relationships they may wish to pursue.

The qualitative component of Brotto et al.’s (2008) study replicates Scherrer’s (2008) findings regarding asexual individuals’ non-sexual desire for romantic relationships. Scherrer finds, when asked to describe their ‘ideal relationship,’ many of those they interviewed express

“interest in some sort of physical intimacy with another or others” (2008:627). Brotto et al. find that several self-indentified asexuals report “wanting the closeness, companionship, intellectual, and emotional connection that comes from romantic relationships” (2008:611). However, as in

Scherrer’s study, this was not found to be a universal trait amongst asexuals. These data led both psychopathologized as a sign of sexual immaturity, and like many of Freud’s theories, we find this embedded in contemporary conceptions of sexuality and health

A SEXY S TORY

9 researchers to recognize and discuss ‘a/romantism’: a phrase generated by asexual communities to distinguish their desire and attractions from sexual connotations and conceptions.

A/romantism and other conceptual categories developed by asexuals highlight the limitations of the dispositional view of sexual orientation that sees an individual’s orientation as based on the “sexual desires and fantasies and the sexual behaviors he or she is disposed to engage [in] under ideal conditions” (Stein 1999:45). One limit of this view is that it attempts to make sense of possibilities and ‘counterfactual situations’ (situations that have not occurred but would reveal an individual’s underlying sexual orientation) that have not actually occurred

(ibid.). Another is that it ignores and often discredits the self-conceptions developed by individuals in favor of a ‘true’ or ‘repressed’ disposition. Instead my study explores asexuality as an identity—which Shively and De Cecco (1977) explain includes the “recognition, acceptance, and identification with one’s preferences” (Brotto et al. 2008:615)—in that it explores the ways in which asexuals conceptualize themselves and negotiate their actions and relationships in context of an identity developed around the experience of non-sexual desire. But let us first look at behavior.

B

EHAVIOR

& C

ONTEXT

: One way to avoid the limits of a dispositional analysis of desire and its relationship to an asexual identity is to focus on objective, or preferably, observable behavior. Many studies on asexuality have collected data on behaviors thought to be relevant to this identity. Bogaert (2004) finds that asexuals, or those who have “never felt sexually attracted to anyone at all,” have a later age of first sexual intercourse and engage in sexual activity less frequently than sexual participants (281). Similarly, Brotto et al. (2008) suggest that there might be a “developmental trajectory whereby the lack of sexual interest in early adulthood may set the

A SEXY S TORY

10 stage for later lack of sexual desire or excitement” (606). Interestingly, Prause and Graham

(2007) do not replicate Bogaert’s (2004) finding that asexuals have fewer lifetime partners than sexuals.

Prause and Graham (2007) recognize that Bogaert’s research is limited by his use of only one item to define individuals as asexual. There are further limitations to his definition, however, in that it makes essential the consistency of never having experienced sexual attraction—a prerequisite that excludes the possibility of coming to an asexual identity after having experienced what one might have considered sexual attraction. This is to say that Bogeart’s definition would find someone who currently does not experience sexual attraction—but has at some point, regardless of duration—ineligible for asexual classification in the context of their research. This grounding of a definition of asexuality in a consistent and unchangeable feature of one’s life not only perpetuates the essentialist notion of asexuality present in its status as an orientation, but also contributes to a process of identity erasure for those who experience variations of an asexual identity. Also, as Hinderliter (2009) points out, a person who does not experience sexual attraction does not necessarily know what sexual attraction feels like. Prause and Graham (2007) point to two additional limitations of Bogaert’s research; the inability to assess arousability or amount of desire in his research, and the lack of questions regarding solitary sexual activity, such as masturbation. However, these too share the limitation of behaviorist conceptions of sexuality; the assumption that the researchers understand how asexuals experience the phenomenon of being aroused or masturbation, in that they assume we all share a common conception of what constitutes ‘sexual’ behavior.

This assumption is problematized by Scherrer’s (2008) research, which finds that physical acts—such as kissing, cuddling, and ‘pleasing’ a partner—were not considered by those

A SEXY S TORY

11 asexuals interviewed to be sexual acts. This finding is in studies that suggest asexuals engage in masturbation while conceptualizing it as nonsexual behavior (Scherrer 2008, Brotto et al. 2008, and Prause and Graham’s 2007). An interesting finding of Brotto et al. (2008) that expands upon

Scherrer’s (2008) findings (that the romantic relationships of asexuals typically tend to be monogamous) is that some asexuals are comfortable with their partner engaging in sexual activities with other individuals, on the condition that this does not become an ‘emotional relationship.’ This points not only to the social construction of monogamy and its boundaries, but also how re/writing meaning is employed in the context of asexuals’ negotiation of relationships with their partners. Scherrer explains that such conceptions of traditionally ‘sexual’ behaviors as

‘non-sexual’ “contributes to a larger social constructivist project as the discourses of sex, sexuality and physical intimacy are challenged and re-written during the construction of asexual identities” (2008:629). This research, then, requires a contextualist understanding of behavior where

“s im ilar superficial moveme n ts m ust be ass um e d to b e . . . d iffe r ent be h aviors, beca u se thei r so ci oc ultur a l c o nt e xt s are d iffe r e n t”; meaning that “t h e na me f o r a b e h av i or i s to b e d iscove r ed e mpi rically by a na l yzi n g t h e context, a nd th e n a m e i s g iv e n (n o t by the m ovement but) in its co n text”

(Landrine 1995:8). This elaborates the role of meaning and context in behavior —but also the necessity for future research to be attentive and sensitive to the subjective conceptions of such behavior in the formation of an asexual identity.

I DENTITY & M EANING : Some of the existing literature on asexuality explores asexual identity (Jay 2003, Prause and Graham 2007, Scherrer 2008, 2010); while other research still encourages it. For instance, according to Bogaert “more research needs to be done on the selfidentification of asexuality ( 2008: 10) and Brotto et al argue that “future research should explore

A SEXY S TORY

12 the labels and meanings that asexual individuals give to themselves and their relationships”

(2008:606). The latter is similar to Scherrer’s request that further studies “investigate the role of asexual identity in negotiating relationships” (2008:638). My research adds to the literature on asexual identities, their meaning and deployment, and their formation and negotiation.

First, let us review the current literature on asexual identities. Recent research regarding the ‘meaning of an asexual identity’ has highlighted the role of context with regard to AVEN and other online asexual community’s influence in shaping the discourse and definition of asexuality.

Hinderliter (2009), addressing the methodological issues of studying asexuality, proposes three hypotheses: first, self-identified asexuals “will have spent more time thinking about asexual identity and spent more time trying to decide if they are asexual or not; second, asexuals recruited online will more closely fit the definition of asexuality on AVEN’s front page because it has likely had a significant impact on their decision to identify as asexual; and third, asexuals recruited online are likely to be strongly influenced by asexual discourse in terms of the categories they use to think about their own experiences” (620). These hypotheses support the

Scherrer’s (2008), findings that the “most common description of an asexual identity closely mirrors the definition given on AVEN’s website,” and that for some asexuals the “internalized meaning of asexuality is hard to separate from AVEN’s own conception of asexuality” (626).

This has also been replicated in Brotto et al.’s (2008) study which identified the consistent theme in self-identified asexuals’ definition of asexuality to be the “lack of sexual attraction”; the conceptual cornerstone of AVEN’s front-page definition. This research explores the events, intentions, and identities that bring individuals to this community, as well as the effects of this community on the process of identity formation. For this exploration of identity formation, I find the works of Foucault and Agamben particularly useful.

A SEXY S TORY

13

T

HEORY

: Foucault describes the discourse on sex as a “petition to know,” in that we are

“compelled to know how things are with it, while it is suspected of knowing how things are with us” (Foucault 1978:78). This discourse, then, making sex an object of knowledge, where it is deployed as something everyone has—sexuality—becomes something that identifies what one is.

The History of Sexuality

, for Foucault is a “history of thought as against a history of behaviors of representations,” one where we examine how different historical epochs problematize and therefore respond to sex (Foucault 1985:13).

Problematization here means the “set of discursive or nondiscursive practices that makes something enter into the play of the true and false, and constitutes it as an object for thought

(whether under the form of moral reflection, scientific knowledge, political analysis, etc.)”

(Foucault 1988:260). Foucault’s history of thought, then, “means not simply a history of ideas or of representations, but also the attempt to respond to this question: how is it that thought, insofar as it has a relationship with the truth, can also have a history?” (O'Farrell 2005:456). For

Foucault 'Truth' is to be understood as a “system of ordered procedures for the production, regulation, distribution, circulation and operation of statements” (Foucault 1980:133). This is produced and perpetuated in society in the form of discourse—“systems of thoughts composed of ideas, attitudes, courses of action, beliefs and practices that systematically construct the subjects and the worlds of which they speak" (Lessa 2006:289). What then produces problems of truth, discourses, and subjects? The answer is dispositifs, also known as apparatuses.

For example, Foucault (1978) explains how “western societies created and deployed a new apparatus—the deployment of sexuality; which has its reason for being . . . in proliferating, innovating, annexing, creating, and penetrating bodies in an increasingly detailed way, and in

A SEXY S TORY

14 controlling populations”; what he described as biopolitics (106). This apparatus, he explained

“operates according to mobile, polymorphous, and contingent techniques of power,” and is

“concerned with the sensations of the body, the quality of pleasures, and the nature of impressions” (Foucault 1978:106). An Apparatus, Agamben (2009) explains, is "anything that has in some way the capacity to capture, orient, determine, intercept, model, control, or secure the gestures, behaviors, opinions, or discourses of living beings . . . not only, therefore, prisons, madhouses, the panopticon, schools, confession, factories, disciplines, judicial measures, and so forth (whose connection with power is in a certain sense evident), but also the pen, writing, literature, philosophy, agriculture, cigarettes, navigation, computers, cellular telephones and— why not—language itself” (14). The “multiplication of discourses concerning sex” is the result of a variety of apparatuses that problematize sex (Foucault 1978:18); their product is subjects.

This is to say an apparatus allows an individual to constitute their self as a constituted subject. For example, the computer I am typing this on, the directed research class I am in, the school I attend, all are apparatuses that allow me to legitimately constitute myself as the author of this text. A subject, then, is “that which results from the relation between living beings and apparatuses” (Agamben 2009:14). This is important to our understanding of Foucault’s larger project of uncovering the “different modes by which, in our culture, human beings are made subjects” (Peters 2003:208). For Foucault, there is no essential subject or subjectivity, rather subjectivity arises from the process of creating the subject. This means that the self is never a sovereign subject, but instead, a mode of subjectification, an apparatus, which creates subjects; which, in turn, are always in relations of power . Since “while the human subject is placed in relations of production and of signification, he is equally placed in power relations that are very complex” (Peters 2003:210). Foucault (1978) did not think that a society could exist without

A SEXY S TORY

15 power relations, since by power he meant the “strategies by which individuals try to direct and control the conduct of others” (39-40); in that what “defines a relationship of power is that it is a mode of action that does not act directly and immediately on others, [but] instead, acts upon their actions” (137).

S

TATEMENT OF

P

URPOSE

: The initial purpose of this research was to examine the following: the formation of asexual identity; the role of family, formal education, friendship, and intimate relationships in forming an asexual identity; the role of an asexual identity in negotiating family, friend, and intimate relationships; and asexuals’ ideals of family, friend, and intimate relationships. Since I use grounded theory in my analysis (see below), and my respondents tended to have less to say in response to a few facets of those questions (instead focusing on problems they experienced prior to an asexual identity, how they found asexuality, the role of AVEN in identity formation, and the relations they have had with themselves and other having adopted an asexual identity) I developed the following research questions using the theory described above. How does an individual come to constitute their self as an asexual subject? What apparatuses and relations of power initiate and contribute to the formation of an asexual identity? What form-of-life is clarified or created in this process?

M

ETHODS

: To achieve the objectives of this study, I used semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative data and grounded theory in analysis.

S

ELF

-N

ARRATIVES

: The qualitative data of this research is my respondents’ personal stories, thoughts, feelings, and experiences—their self-narratives. Self-narration is used to come

A SEXY S TORY

16 to “know ourselves,” to “apprehend experiences and navigate relationships with others,” to situate in “time and space [what] engages only facets of a narrator’s or listener/reader’s selfhood in that it evokes only certain memories, concerns, and expectations” (Ochs 1996:21-22). This is important since, if one’s integration of an asexual identity has “some efficacy in transforming identity, that efficacy should be sought first of all in the narrative” (Staples and Mauss

1987:143). This is because “central concerns cited” by self-identified asexuals, as leading up to and constituting the conversion event also manifest themselves in stylistic features of the conversion narratives” (Stromberg 1990). So while “narrative does not yield absolute truth,” under certain conditions, particularly those where a transformation in identity has occurred, narratives will likely reveal “more authentic feelings, beliefs, and actions and ultimately to a more authentic sense of life” (Ochs 1996:23).

P

ARTICIPANTS

: I began by obtaining permission from the Webmasters of both the

Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN), at asexuality.org, and LiveJournal (LJ), at asexuality.livejournal.com, through e-mail. This e-mail included an introduction of myself, contact information, as well as a detailed explanation of the proposed research purpose and procedures (see Appendix A). After obtaining permission from the Webmasters, I recruited participants from AVEN and LiveJournal (LJ), via forum posts (see Appendix B). The Forum post contained an invitation to self-identified asexuals over 18 to participate in an interview exploring identity formation, including a detailed description of the research and what participation entailed, in addition to a copy of the informed consent form (see Appendix C) and the contact information for my faculty supervisor and myself. I interviewed the first 18 selfidentified asexuals that responded to my request to participate in this study.

A SEXY S TORY

17

P ROCEDURE : All interviews were scheduled via an e-mail that included a list of potential interview mediums (telephone, Skype, AOL Instant Messenger, Facebook chat, Google chat, or

Google Voice) in addition to the link where each can be downloaded (see Appendix D). Each interview followed the pre-established interview protocol (a semi-structured interview instrument, see Appendix E), which involved asking participants if they were comfortable being recorded (and if not, taking notes), obtaining recorded or written informed consent, and asking questions pertaining to identity formation. Each interview lasted 45-90 minutes, and concluded by thanking the interview participant and asking if they would be willing to answer future follow-up questions. The recorded interviews were then transcribed and checked for transcription mistakes in order to avoid errors.

E

THICS

: As a result of the social stigma surrounding asexuality, ethical precautions were taken. All information gathered during this study remained confidential in a password-protected computer throughout the course this research. In order to protect participants’ identities I change their names, with only my faculty advisor and I having access to information that could connect responses to respondents. All audio recordings and other data were deleted upon completion of this project.

A

NALYSIS

: Following each interview I analyzed the transcription, using open coding in order to generate categories of meaning from the data collected. These categories were, then, through the process of axial coding, examined for theoretical connections based on my findings and the corresponding research data and theory available. Selective coding was then employed in order to develop an explanation based on the interconnection of the categories identified. To

A SEXY S TORY

18 increase the validity of this analysis, I reported findings back to many of the participants, and provided them an opportunity to give feedback. After analysis of the first few participants’ interviews, I refined my interview questions in order to collect data that allowed me to elaborate the categories of meanings located. After having completed the analysis of all participants’ data,

I again shared my findings with them via e-mail.

R ESULTS : A SEXY S TORIES

PROBLEMATIZATION | EXPLORATION | BECOMING ASEXUAL

AND A FORM

-

OF

-

LIFE

S HADES OF G REY : N ARRATIVES OF A P ROBLEMATIZED S ELF

Most people on AVEN have been asexual for our entire lives. Just as people will rarely and unexpectedly go from being straight to gay, asexual people will rarely and unexpectedly become sexual or vice versa. Another small minority will think of themselves as asexual for a brief period of time while exploring and questioning their own sexuality. (AVEN: Overview Page)

It's not so much separate experiences that make me think I'm asexual, as it is the whole effect of my life . . . my behavior just makes sense when I think of it in an asexual perspective. (Andale)

Many of the stories I heard interviewing self-identified asexuals reiterated the ideas above. Very few narratives of coming to an asexual identity included sudden or unexpected changes in behavior, desire, or personality; instead most involved something subtler, a process of gaining clarity, adopting an identity, and finding community. My findings suggest that this undertaking begins with a process of problematization, the way in which something (such a

A SEXY S TORY

19 behavior, desire, or personality) becomes a problem. It is when this conflict is internalized, when one perceives their self to be the problem or its cause, that such a process can culminate in an exploration of self; a search for meaning that provokes the possibility of asexuality.

For instance, situations where expectations, intentions, and desires in a relationship did not align were the first sign of a problem for several respondents. For example, Andale explained, “my best friend took some signals of mine the wrong way, came on to me, and I freaked out.” Similarly, some asexuals, such as Corbel, described not having “even considered the possibility” of such flirtatious signals, let alone having someone “come on” to them. For a few, a misreading of these signals interfered with creating (Tahoma) and continuing (Bell) friendships. These interviewees explained that when unexpected, such experiences could be not only startling but also problematizing.

For others, it was through a sexual relationship that concerns developed. Some expected sexual feelings to arise from their sexual relationships, but they did not. According to Bell:

I’d been in the relationship two months and I was beginning to think some sort of sexual feelings should have turned up by now. . . . I started to panic, I started to think something’s really wrong with me, because I had never heard of anyone being like me before.

Internalization of the problem can be seen in Bell framing the conflict as something being

“wrong with” them as result of not knowing of others “like” them. This also reflects the absence of an available known or coherent explanation in such situations, and the role this plays in the process of problematization. Still others experienced, instead, a misunderstanding with their partners as to the place of sex and sexual feelings in their sexual relationships. Arial elaborates:

He needed to have a sexual relationship to express his love for me, and that really blew me away. I remember saying to him, ‘can’t you just say I love you, can you show you love me by how you act and by saying it?’. . . It made me realize the whole love and sex relationship tend to go hand and hand for sexual people, and I

A SEXY S TORY

20 guess I never really realized that before. I thought sex was just something you did; you know, when you felt aroused or something, when the mood took you.

Likewise, for some asexuals, confusion arose from the act of having sex. For example, Franklin said, “I couldn't ‘understand’; sex made me feel inferior in some way.”

Finally, for some, a long, mostly passive process of problematization cumulated in an abrupt and sudden realization absent of a particular impetus. For Lucida, what inspired exploration of asexuality was the:

Realization that I’d only ever been on one date and that I hadn’t enjoyed it or felt any desire to go on more with anyone else. . . . The realization that I’d gone through high school without ever once wanting to do anything but hang out and talk with and possibly hug the classmates I found romantically attractive. . . . I experienced plenty of sexual arousal, it never had anything to do with any particular person, and I never wanted to share the feeling with anyone else.

These findings suggest that hugging, flirting, dating, sexual feelings, and even sex itself, should not be thought of in terms of universally common behaviors or desires, but instead as a contextualized “social acts”; one where due to the backgrounds and situational context of individuals, these behaviors can have very different meaning and effects (Dworkin 1987,

Landrine 1995). This can be seen in the quotes above, where some people have come to equate sex with love and desire, making the act of sex for them an affirmation of both in addition to other things, 3 while others conceptualize it differently, affirming something else. For many of my respondents, what this initially affirmed is a problem with their self. For example, several interviewees explained, in response to the problematizing situations described above, feeling like there was “something wrong with me” (Franklin, Geneva, Bell Arial). Others felt abnormal (Gil,

Corbel, Menlo), and even sick (Franklin). Here we see conflict is internalized, making one’s self

3

An affirmation also of a variety of other things such as masculinity, femininity, homosexuality, even possibly of being human (in that some assume all humans possess sexual instincts).

A SEXY S TORY

21 a problem that requires an explanation.

Looking for resolution to these unnamed problems—unexpected sexual experiences between friends, feelings of uncertainty or inferiority with regard to sex, and others—all of my respondents eventually researched asexuality; however, a few first figured out other ways of addressing these problems temporarily, prior to adopting an asexual identity. For example,

Andale describes initially reacting to their friend’s sexual overture:

When my friend was interested in me in high school . . . I sort of made myself think I must be gay; because he was being so repulsive at the time, and my not knowing about asexuality, I knew I had to be between straight and gay. . . . If he was being so disgusting, then I had to be gay.

“Deep down” however, Andale explained, “I couldn't really relate.” Similarly, Corbel, describes

“avoiding topics related to sexual identity,” altogether and being “infamous for keeping (their) sexuality a secret.” Others, such as Gil, didn’t encounter the same situations as Andale and

Corbel and “never thought [their lack of sexual attraction] was anything out of the ordinary,” because they went to a “boarding school that was very academically elitist and everyone was just focused on academics”; until they became 21 and their “just-a-kid” explanation was no longer an option. Gil elaborates:

People my age, you know, they start talking about these things, and I’m like okay.

It’s not something I’m very interested in at all. I used to think, it’s because I’m still a kid, um you know, it’s not really that weird, and I don’t necessarily think it’s that weird, it’s just different. But, um, basically, I still kept trying to justify it by saying I’m just a kid, why are people having sex at this age? I’m about to turn

21 and I’m like okay, I can’t really use that excuse any more.

In a similar fashion, Bell, whose relationship was problematized due to a lack of “sexual feelings,” also describes an additional, even earlier, problematization of self. They recount maturing a “lot quicker then most of my classmates”: clarifying, “I was going through puberty like everyone else, but I wasn’t having to deal with the whole sexualization of everything.” They

A SEXY S TORY

22 elaborate: being “raised a strict Christian . . . I used to think my prudishness was just my

Christianity, and then I realized, no it’s not” (Bell). Like Bell, Andale, Corbel, and Gil also realized their explanations were not working for them. This too, like the situations described earlier, provoked an investigation of self which resulted in an exploration of asexuality. The many details and socio-cultural variables at play in these events make up a process of problematization that is pivotal to the construction of an asexual identity; not only because they initiate an exploration of self and of asexuality, but also, as we shall later see, they are the foundations of one’s personal use and understanding of asexuality.

To summarize, the norms and discourses that structure participation in one’s relationships and socio-cultural environments, particularly those which prompt a search for asexuality (see above), can problematize an individual’s sense of self and self in relation to others. Ironically, the expectations, intentions, and desires that are problematic in the situations described above, undoubtedly developed socially in part from other situations, relationships, and environments.

This is to suggest that the wide array of expectations placed on an individual in any given sociocultural context can sometimes be contradictory, and when this results in an unintelligible conflict an individual must find meaning to address and make sense of the situation. Since thought is “something that is often hidden but always drives everyday behaviors” (Foucault

2003:172), and culture requires that we construct both each others’ thoughts and behavior

(power) through various apparatuses,

4

a double bind of an individual in this web of power is undoubtedly confusing. As Foucault (2003) explains, when “people begin to have trouble thinking things the way they have been thought, transformation becomes at the same time very

4 "Anything that has in some way the capacity to capture, orient, determine, intercept, model, control, or secure the gestures, behaviors, opinions, or discourses of living beings” (Agamben, 2009).

A SEXY S TORY

23 urgent, very difficult, and entirely possible” (172). This ‘breakdown’ “provokes a space of possibility,” where one can transform their self, their relationships, and their lives, “precisely because things don’t work smoothly anymore” (Haraway 1999:115). Unlike others who are stigmatized, however, who “[learn] and [incorporate] the standpoint of the normal, acquiring thereby the identity beliefs of the wider society and a general idea of what it would be like to possess a particular stigma” (Goffman 1963:32), the asexual individual is faced with a stigmatizing situation, absent of known or coherent stigma in mainstream society that they could easily acquire.

5

This is to say that without popular knowledge of asexuality (or even Hypo-active

Sexual Desire Disorder for that matter),

6

communicating the multiple and possibly contradictory intentions, expectations, and desires necessary to address problematizing situations requires individuals seek out an alternative discourse, one that will make sense of their behavior and normalize their self-narrative. For some, this discourse is available and attained through the apparatus of the Internet, particularly AVEN, an online community for asexuals—in the form of asexuality.

F INDING I DENTITY : A N E XPLORATION OF S ELF , A SEXUALITY , AND C OMMUNITY

5 An exception being the biomedical discourse on hypoactive sexuality disorder, which is qualitatively different in many regards from asexuality; however this is beyond the scope of this current project. For now I will leave you with this quote from Franklin, who explains, “asexuality in the sense of AVEN and other organization, also holds a sense of community and belonging. Being asexual, especially within the medical field, is seen that something is

" wrong " instead of an actual orientation or valid way of life . It is something that must be ‘fixed.’ Being asexual to me, means having that lack or desire or need for sex, but also being okay with it and not feeling inferior for it.”

6 While available to those who seek a medical explanation of themselves and their situation, HSDD does not seem to be a very well known or popular medical condition, so like asexuality, it is not a readily available explanation.

A SEXY S TORY

24

One of the main motives to identify with a social group is to “gain self-esteem, to reduce uncertainty about oneself, and to fulfill the basic need to belong” (McKenna 1998:682). For those with “mainstream and culturally valued identities, opportunities for group identification are readily available”; however, for those who “possess culturally stigmatized identities, especially identities that are concealable from others, this is not the case” (ibid). Therefore, the creation of communities for marginalized groups plays an especially important role in ‘easing’ stigma for individuals with ‘concealable’ (Frable 1993) or ‘discreditable’ stigmas (Goffman 1963). This is because those with visible stigmas are often “able to see that there are similar others and so do not feel so unique or alone,” whereas those with “concealable stigmas cannot and [therefore] tend to feel more different from other people” (McKenna 1998:682; see also Frable 1993). This is largely the consequence of there being “no visible sign of others who share the stigmatized feature,” for those with concealable identities (ibid). So it is in communities that those with discreditable identities can, for the first time, “reap the benefits of joining a group of similar others: feeling less isolated and different, disclosing a long secret part of one’s self, sharing one's own experiences and learning from those of others, and gaining emotional and motivational support” ( McKenna 1998:682; see also Archer 1987, Derlega et al. 1993, and Jones et al. 1984).

Again, however, since there is little popular knowledge about asexuality, there is not necessarily even a clear stigma that an individual would ‘conceal’ due to fear that it might

‘discredit’ or ‘spoil’ one’s identity, let alone a stigma that one could use to locate community.

Instead of a pre-packaged, socially-recognized stigma, there are stigmatizing situations and experiences that can allow an individual to adopt and develop an asexual identity. One is to locate a community conducive to what David Jay (2003), the founder of AVEN, describes as a

A SEXY S TORY

25

“collective identity”: a "shared definition of a group that derives from members' common interests, experiences, and solidarity" (Taylor and Whittier 1999:170). My suggestion, however, is in conflict with the hypothesis proposed by Jay as to how a collective identity is formed, or more specifically, the limiting criteria of its formation. In an unpublished paper on collective identity formation for asexuals, Jay states the following:

In order to find an asexual collective identity to help understand xe’s experiences an individual must first name those experiences as asexual. . . . To even arrive at

AVEN asexuals must have reached a relatively high level of self-awareness about their (non)sexuality and possess the foundations of an asexual identity. This filtering process contributes to community cohesion but greatly impacts its size and diversity; people who do not for some reason spontaneously label their experience as “asexual” are not granted access. (Jay 2003:8) 7

My findings (above) suggest that the “self-awareness” of an individual’s nonsexuality and

“foundations of an asexual identity” that asexuals must have to arrive at AVEN both stem from a process of problematization that can take a variety of forms; that is then internalized, encouraging individuals to understand their experiences, a process that leads some to asexuality.

While some individuals do find AVEN having already named their experiences as “asexual”; others find asexual community before finding the word. This is to say that one’s access to AVEN is not contingent upon identifying as asexual per se. Still, for many, their asexuality is contingent to access to AVEN. Finally, those that do not spontaneously understand their experience through asexuality are not denied access; rather there are a variety of ways an individual can participate without having adopted this collective identity, such as lurking the forums or clarifying concerns in the Q&A. After all, nowhere in the registration process required

7

I believe this statment might have stemmed from AVEN’s 2003 statistics presented in Jay’s paper that “show that most users arrive at the site either by typing the word ‘asexuality’ into a search engine or by typing directly the address: http://www.asexuality.org” (Jay 2003:7-8).

A SEXY S TORY

26 to participate in AVEN does it suggest that doing so entails identifying as an asexual.

A few of my respondents did first—at least initially—encounter asexuality before searching or ‘Googling’ the word, and consequently finding AVEN. Franklin, for instance, first encountered asexuality during the Toronto Gay Pride parade where “there was an asexuality float,” which inspired them to go “home and Google it.” For some this type of encounter resonates enough to evoke a search; however, it is not until after having already accessed AVEN that they label their experience as asexual. For example, Menlo first heard about asexuality in a

“psychology class in college, [where] the teacher brought up the topic of asexuality, saying that about 1% of the population . . . was asexual” and explained what it was. “I indentified with it a lot,” Menlo said, “but it wasn't until I started to do more research just to be sure, that I started to self-describe as asexual.” While all of my interviewees eventually used search engines, such

as

Google, to find communities, many of my interviewees found asexuality through such searches, not prior to them. Bell, for example, explained:

One night I was up all night typing everything I could think of into Google. . . .

Celibacy, that wasn’t right, that wasn’t what I was feeling; ‘don’t like sex,’ and it came up with all these relationship issues, and I’m like, ‘that’s not right either’. . .

. I just kept typing stuff in again and again, and then I found AVEN. I think I actually found Wikipedia first, an article on it in Wikipedia, and I was like ‘huh, hold on.’ So then I went into AVEN, read everything in it, watched all the video things—you know the Montel, the Fox News, the CNN, all of it—I was like, ‘I found home!’ It was that night, and I’ve never looked back.

Basker had also “been up all night,” “reading random Wikipedia articles” when they “found a link to AVEN.” They described reading the FAQ, Asexual Perspectives, and other materials on the site as “literally eye-opening,” explaining “I realized the definitions and descriptions of asexuality fit how I felt, and some of the ace [asexual] blogs I read felt like I was the one who had written them”. Still, similar to Menlo above, for Basker, it was not without having “asked some questions in the forums,” gaining “clarifications on some of the FAQ” and hearing “others'

A SEXY S TORY

27 personal experiences of asexuality,” that they adopted the label that “felt like it fit.” In the same way, Gil first found asexuality unintentionally while browsing Wikipedia. They explained, “[I] went to the asexuality entry on Wikipedia and started reading everything on it and it seemed like something I could really relate to” and “from the Wikipedia entry I found out about AVEN and started looking into the forums and the LiveJournal community and new ones from there” (Gil).

Like Gil, Geneva also “searched for any LJ equivalent” to AVEN. Menlo explains, since they were “interested [in asexuality] and I had a LiveJournal account already, it made sense to join.”

Already having a LiveJournal account, people like Franklin, “just added it to [their] list of communities.” This was more convenient for some of my respondents, since they were “usually more active on LJ than other sites” (Geneva).

Similarly, several of my respondents, including Geneva, were open about their asexual identity on their Facebook page (Bernard, Andale, Arial). Basker even used Facebook to come out as an asexual after their experiences on AVEN, sending links via AVEN to anyone who “had trouble understanding” them when they came out. This suggests that an asexual collective identity, and access to communities that create it, does not require that an individual “first name those experiences as asexual”; rather the search can lead to both, allowing them to be deployed in a variety of ways.

Others still, as Jay suggests, do spontaneously name or label their experience as asexual, or a variation thereof, such as non-sexual (Georgia), without previously encountering such terminology; neologisms that eventually connected them to AVEN. Tahoma for example, explained:

I started using the word "asexual" to describe myself when I was about 14 or 15.

Back then I didn't know what the exact definition was. I just used my knowledge of language to make a word that meant "not gay, not straight" in terms of sexual orientation. I remember telling my parents around that time I thought I was

A SEXY S TORY

28 asexual, and they thought I didn't know what I was talking about. They asked me if I knew what that meant. I said something like, yeah, it means I’m not interested in anyone in that way.

What brought both Tahoma and Georgia to an asexual/nonsexual identity, and connected them to other asexuals and communities providing an asexual collective identity was, as with the others, a process of problematization. Unlike Corbel’s situation from the previous section, where they avoided entirely questions of sexual orientation, for Tahoma the conflict that elicited an asexual explanation was a desire to participate in conversations involving orientations without one that fit. They explained, “my friends were talking about their own experiences [with sexuality],” and

“I should be able to throw my 2 cents in. . . . Being a big part of a GSA, I thought I could and should be open about it” (Tahoma). Their parents, who they later explained their asexuality to, even asked questions about Tahoma’s sexual orientation after they joined their GSA (Tahoma).

The conflict, then, was simply an initial lack of an orientation to employ when prompted for one.

Unlike those who developed other strategies for dealing with conflict and the eventual problematization of self (Christianity, school, age, see earlier section), prior to or separate from

AVEN’s asexuality, these sexual-identity-oriented explanations not only proved sufficient, but also more directly connected them to others to whom they could relate.

8

Once in college Tahoma found AVEN out of curiosity and Georgia, who created their own online resources for ‘nonsexuals,’ found AVEN through a link to their own site, adopting the ‘asexuality’ terminology for the sake of consistency. These findings lead me to believe that an individual does not have to spontaneously name or label their experiences as asexual in order to find or gain access to

AVEN, but instead, a variety of problems that individuals experience provoke a search that leads

8 This feature seem to alluded to the relation of sexual identities and orientation in the process of problematization, as well as their relation to ‘regimes of truth’ and the legitimacy they entail

A SEXY S TORY

29 them to name and label their experience and selves asexual, and that AVEN is one of a few apparatuses they can encounter during such an exploration that allows them to do so.

This is to also suggest, however, that the “pre-existing criter[ion]” for an asexual collective identity is not

"preexisting group ties," (

Taylor and Whittier 1999:170), nor is it necessarily the spontaneous labeling of experience as asexual (Jay 2003), but rather there are different problematizing processes and corresponding explorations that create and continue the conditions for a collective identity. This is because, this process, when added to a community’s infrastructure—such as AVEN’s website and forums—creates a situation where people who

“tend to have similar learning experiences regarding their plight” come together to experience

“similar changes in conception of self; a similar ‘moral career’ that is both cause and effect of a commitment to a similar sequence of personal adjustments” (Goffman 1963:32). AVEN provides individuals with a new discursive formation of sexual orientation; one that extends the typical heterosexual/homosexual, and maybe bisexual, framework to include asexual, someone who does not experience sexual attraction. The asexual collective identity AVEN creates supplies more than an explanation of behavior and desire, it also provides an “ideological language” that yields the “resources to integrate denied intentions into a coherent set of intentions—an identity”

(Stromberg 1990:53). To illustrate this point, Verdana explains:

When I first joined (AVEN) it was more of an abstracted idea that fit me and explained some of thoughts/behaviors and so on, but being in the community morphed it into an identity, something a little more tangible. I suppose it gave me a sense of identity where there was only a sense of confusion.

Before it was like

I'm not sexually attracted/don't like sex because [pause] well, I don't? But now I can say I'm asexual, and explain what that is. . . . It's kind of grounding, in a way.

Makes things seem more concrete, less abstract. (emphasis added)

This is to say that the orientation AVEN provides, in turn, becomes an explanation of self—an identity—a tool individuals can employ, giving meaning to the situation and allowing them to

A SEXY S TORY

30 narrate that part of their selfhood that was previously invalidated, ignored, or otherwise problematized as a consequence of the normative expectations of sexuality.

What makes this identity collective is an environment provided by AVEN that is conducive to the structured development of narrative (Heath 1982). An asexual self-narrative— developed through the ‘dismantling’ of previous narratives that, left unexplained, or more importantly, unresolved—rectifies a problematized self through the forums, specifically the

Q&A (Michaels 1990). The adoption of an asexual identity, then, assists the individual in confronting the problematic situations from which it originally arose, but also provides new conditions of community and the collective construction of identity. Goffman explains that it is through these communities that the individual “learns that he possesses a particular [identity] and, this time in detail, the consequence of possessing it” (1963:32). This includes the ability to retroactively self-narrate one’s past, as can be seen with the “oh, that’s why I was like that,” comments (Verdana). This is exemplified in this quote from Geneva, where a “failed relationship,” with their “would-have-been fiancé” led them to AVEN, where they found the

“ideological language” and self-conception of an asexual identity:

Some years ago I was in love with a wonderful man. I had every intention to marry him; in fact, and even went so far as to move 2000 miles away from home to be with him. But once I was with him, I found myself strangely reluctant to be intimate with him. I had no idea what was wrong; if I loved him, shouldn't I be unable to keep my hands off him? Understandably this led to a rift between us and we broke it off. It wasn't until after I'd come back home and did some serious selfexamination that I figured out I didn't want physical intimacy at all. . . . Sometime after that I discovered AVEN online and the actual name for what I was.

B

ECOMING

A

SEXUAL

: N

EGOTIATING

N

ARRATIVES AND

C

ONSTRUCTING AN

A

SEXUAL

I

DENTITY

ASEXUAL: A PERSON WHO DOES NOT EXPERIENCE SEXUAL

ATTRACTION

(AVEN: Front Page)

A SEXY S TORY

31

There is considerable diversity among the asexual community; each asexual person experiences things like relationships, attraction, and arousal somewhat differently. . . . There is no litmus test to determine if someone is asexual.

Asexuality is like any other identity—at its core—it’s just a word that people use to help figure themselves out . If at any point someone finds the word asexual useful to describe themselves, we encourage them to use it for as long as it makes sense to do so (AVEN: Overview Page)

While not explicitly required, the adoption and internalization of the ‘collective identity’ of the community is part of the process for many members of AVEN. This occurs through an individual’s integration and application of the “ideological language” of the community to their own self-narratives, which enables them to “come to terms with enduring problems of meaning in their lives, bringing about the sense of having been transformed” (Stromberg 1990:43); but also on an interpersonal level, through the dismantling, negotiation, and construction, of a previous self-narratives through participation in and interaction with the online community

(Michaels 1990; Heath 1982; Rogoff 2003). This transformation of self, which originally arose in “response to worries, complaints, and conflicts,” can now be deployed to resolve them,

“normalizing life’s unsetting events” (Ochs 1996:27); and additionally, provides access to the conditions of a community that does not reproduce the problematizing features of the previous socio-cultural environments, and as we shall see later, a ‘moral career’ of continuing these conditions for others. For example, continuing Bell’s story from earlier, after staying up all night searching Google they found AVEN. They explain:

I was like, ‘I found home!’ It was that night, and I’ve never looked back. And then I started to come out to my flatmates, my boyfriend, and then my family.

And then I became very active in the media. And I’m still a very active advisor on

AVEN. David Jay forwards e-mails that people send and I answer them. You know people who are struggling or want people to talk to.

Recent research regarding the ‘meaning of an asexual identity’ has highlighted the role of

AVEN and other online asexual communities in shaping the definition and discourse of

A SEXY S TORY

32 asexuality. Hinderliter, addressing the methodological issues of studying asexuality, proposed three hypotheses:

First, [self-identified asexuals] will have spent more time thinking about asexual identity and spent more time trying to decide if they are asexual or not; second, asexuals recruited online will more closely fit the definition of asexuality on

AVEN’s front page because it has likely had a significant impact on their decision to identify as asexual; and third, asexuals recruited online are likely to be strongly influenced by asexual discourse in terms of the categories they use to think about their own experiences. (Hinderliter 2009:620)

Many of my respondents’ narratives, support all three; however I propose a few amendments. In addition to the influence of AVEN’s

Front Page definition on identification and understanding, my findings suggest that the Overview , FAQ , and other informative resources on the site endorse a diversity-oriented discourse on asexuality. This discourse emphasizes a pragmatic and flexible conception of asexuality that validates individual differences in definition.

Also, the Forums and the interactions between users that they facilitate don’t simply supplement the Front Page , but are, rather, active areas of identity formation, negotiation, and development.

Moreover, the Forums significantly influence the discourse on asexuality as well as an individual’s decision to identify as asexual and participate in the online community. Finally, current research suggests that asexuals employ AVEN’s

Front Page definition of asexuality, or what I refer to as ‘general definition’ of asexuality (Brotto et al. 2008, Hinderliter 2009, Scherrer

2008). My findings suggest this ‘general definition’ has likely been distilled from additional personal, romantic, and ‘diversity-oriented’ understandings of asexuality.

AVEN’s Front Page definition of asexuality is noticeably influential in many individuals’ understanding of their asexual-self; subtler still is the role of the site’s informative resources and the forums, and the understanding they create. To explore their effects, we must

A SEXY S TORY

33 examine the ways in which individuals initially engage with AVEN and how these forms of participation change.

There are a variety of ways individuals can engage with AVEN without registering or even adopting an asexual identity. Lucida, for instance, was drawn in by the FAQ since, they explain, “[the information] sounded so much like myself.” After the

FAQ , they explained, they continued searching the site for additional “information wells” to help them understand themselves (Lucida). Similarly, Franklin describes their self as a ‘lurker,’ someone who follows the forums without posting. Due to their job, they explain, “[I] didn't have time for online communication,” but “[lurking] helped because even if I wasn't involved in those conversations,

I knew they existed, and were validated so I felt okay with myself.” Franklin is still a lurker, but occasionally has “small conversations about common interests, movies, jobs, etc. . .” with members of the community; others find new ways of participating in this online community.

Andale for example, is ‘lurker’ turned ‘mod.’ They explain, “[I] lurked on the main three boards,

Q&A , Musirants , and Asexual Relationships , but then I went to Tea and Sympathy

,” where they became a moderator. For Verdana, after a very brief lurking period, “prefer[ing] to read a bit before [they] actively participate[d],” they explain, “I wrote my own introduction thread, but I didn't post much else to begin with,” saying, “I'm often a bit shy and slow on forums.”

While individuals can feel the effects of validation through mere awareness of community and identity, participation in the online asexual community largely entails interacting on the forums. “It's been really helpful,” Menlo explains, “any time I have any questions/doubts I post them up without fear of ridicule or anything . . . it just feels safe.” Menlo describes learning about aromanticism through the forums calling it an “eye opener” they “might not have known about if it wasn't for the community.” Similarly, Gil describes talking to people on the forums

A SEXY S TORY

34

“to figure out . . . why this need to masturbate.” This is not one-sided, however; Geneva describes using the forums “to ask questions when [they] first found them” and then later, after having developed their new moral career, “to offer support and empathy to other asexuals.”

“They've helped me,” says Andale, “everyone is intelligent, helpful and kind and so openminded. . . . I suppose we have to be,” they explain, AVEN “helped me come to terms with

[asexuality] and made me want to give back to that community.” Andale was not my only respondent who is “involved in asexuality more . . . because [they] want to help other people.”

Similarly, Lucida watches mostly “for opportunities to help people clarify their thoughts on the matter, and to participate in any research people want to do in order to help further understanding.” Such interactions between members of this online asexual community are pivotal to the formation of asexual identities as well as people’s decisions to participate in the online community. As Gil explains:

The Forums were actually pretty useful, there’s so much still to learn about sexuality, you know, it’s just this long spectrum, so it was actually very useful going onto the forums and finding out that some people are hetero-romantic, some people are aromantic, some people still have some type of sex drive it’s just not directed towards any one. . . . I was just very clueless about stuff before that, and this was helpful to helping me find out more stuff about myself and trying to realize that its not something that’s abnormal or anything, that it’s just how I am.

It is in this way that the forums are to the ‘diversity-oriented’ discourse on asexuality, what the front page is to the ‘general definition.’ The “considerable diversity among the asexual community,” where “each asexual person experiences things like relationships, attraction, and arousal somewhat differently” (AVEN: Overview), is most apparent in the

Forums . The perpetuation of this discourse, however, is not as passive as its front page equivalent. The terms, categories, and variations of asexuality that these individuals use to think about and describe their own experiences—their asexual, (a)romantic, libidoist, etc. self-narratives—are practiced,

A SEXY S TORY

35 shaped, and refined, during the communicative interactions with other members of the community in the forums through posting (Michaels 1990); but also by having submitted post, so anyone, especially lurkers who miss out on the former, can observe through reading (Heath

1982). This process functions to facilitate the fluidity of a community conception of asexuality.

This is exemplified in Calibri’s explanation of asexuality:

In the community there are fetishists and their sexually is expressed, it exists, but it’s not something that requires a partner, or what most people think of as ‘sex.’

So, um, we sort of take people in with the asexual category, for anyone who feels alienated by what the rest of society considers to be normal, regarding having sex or the lack there of. . . . I mostly view it as people who don’t fit into a straight heterosexual box, or like a straight/gay box . . . anyone who feels like they are not fitting into a normative sexuality with their orientation or who rejects all orientations and just [doesn’t] have sex . . . it’s what it means to you . (italics added)

Just as an individual can integrate the ‘general definition’ in one’s conceptual understanding of asexuality, without it negating a more personalized understanding, one can learn and acknowledge the ‘diversity-oriented’ discourse while still adopting the generalized definition as one’s own. Gil describes the “confusion at first when you’re trying to define

[asexuality], because you’re like, that must mean that I can’t have romantic feelings at all, what exactly does that mean for my sex drive, all those type of things. . . . I know there [are] varying degrees of asexuality and people have different interpretations, but for me basically it means, you know, not having sexual attraction to any one person in particular.” Some asexual individuals have multiple conceptions of an asexual identity; these are often separated as, ‘definition’ and

‘personal-definition.’ Some examples are as follows:

I Simply, I see it as a lack of sexual attraction. (Verdana)

I guess it can be more complicated than that, but that is how I see it at it's simplest. . . . There are other forms of attraction that can complicate matters, such as aesthetic and emotional attractions [that] would be especially complicated in seeking a relationship where the partner is not asexual, or understanding. . . . It

A SEXY S TORY

36 can be sometimes hard to explain; I imagine that explaining sexuality to an asexual, or asexuality to a sexual may be like explaining colour to a blind person.

Asexuality seems to offer a different understanding on the way relationships and attractions work. (Verdana)

[Asexuality is] a diminished or nonexistent capacity for feeling sexual attraction to other persons. This does not include romantic or emotional attractions, and does not rule out the possibility of having a libido without requiring anyone else’s assistance with satisfying it. (Lucida)

Most of the time, I just feel like the sexual population has an interest I don’t, akin to wanderlust or the creative drive. Not everyone likes to travel. Not everyone feels compelled to create things. Not everyone craves sexual contact with others.

It’s a very common interest, to be sure, so not having it is seen as stranger than having it, but I don’t feel like I’m missing a piece of myself. I just have other interests. It also means a kind of freedom, for me, because I’m reclusive and needing to form sexual relationships would mean having to suffer through a lot more social contact. It’s one less pressure on me, which makes me a little bit happier than I would be otherwise. (Lucida)

Asexual means, by definition, that I have no sexual attraction. (Corbel)

Personally, it means that I'm wholly uninterested in the sexual nature of relationships. . . . I feel that before discovering asexuality, I was always more interested in other aspects of relationships (not specifically romantic/sexual relationships). I was always more interested in emotional and intellectual connections. Upon discovering asexuality, I felt I could more open[ly] seek out emotionally and intellectually stimulating relationships. Therefore, asexuality means, to me, that I can have more complex relationships built upon other areas of life. . . . Generally, I say that I'm more emotionally attracted to females. This is evidenced in the fact that a large majority of my friends are women. (The second largest group of people behind women are gay men in my group of friends.) As per intellectually, I feel as though if I'm intellectually stimulated by a friend, then

I am much more likely to be attracted, not to a relationship (Oh, the vocabulary of asexuality!), [but] to them and would want to be around them more. (Corbel)

The issue at hand here is not that one is more true than the other; rather the two provide different functions in the process of self-narration. The ‘definition’ employed is the ‘generalized definition’ of AVEN’s

Front Page . This is the base of the collective identity of their community

A SEXY S TORY

37 and their moral career as an asexual. This moral career, or one’s sense of self, identity, and role in the community, my findings suggest, includes a series of personal adjustments in selfunderstanding (asexual, romantic, libidoist, etc.) and participation in community (questioning, socializing, outreach, etc.). There are many reasons, then, why an individual might use this definition: to succinctly define asexuality to a friend or researcher, to perpetuate the discourse of a sexual orientation that includes asexual, or as a few of my respondents explained, to use an identity that fits them well enough. For those whose identity was not synonymous with the

‘general definition,’ the latter option, the ‘personal-definition,’ often explained something beyond lack of sexual attraction; including other forms of attraction and interest. This finding requires that we try and understand an asexual form-of-life; what Tiqqun (2010) describes as a

“human unity,” or a relationship between human subjects, based on a charge that orients and attracts bodies; what Foucault called a mode of being, a way of life, or a membership of a particular ‘we’ if you like.

To elaborate, I draw upon Foucault’s discourse on homosexuality. Foucault (1981) encourages people to “distrust the tendency to relate the question of homosexuality to the problem of ‘who am I?’ and ‘what is the secret of my desire?’” The problem,” he explained, is

“not to discover in oneself the truth of one’s sex, but, rather, to use one’s sexuality henceforth to arrive at a multiplicity of relationships” (ibid). “Perhaps,” he said, “it would be better to ask oneself, ‘what relations, through homosexuality, can be established, invented, multiplied, and modulated?” (ibid). He found this question more interesting, since he thought to be ‘gay,’ is “not to identify with the psychological traits and the visible masks of the homosexual but to try to define and develop a way of life”; meaning “much more than the sexual act itself,” to “want guys was to want relations with guys . . . not necessarily in the form of a couple but as a matter of

A SEXY S TORY

38 existence: how is it possible for men to be together” (Ibid). Similarly, then, an asexual mode of life, or form-of-life, necessarily exceeds the absence of sexual attraction; therefore, any attempt to try to conceptualize and develop an asexual form-of-life would require a exploration of the relations ‘established, invented, multiplied, and modulated’ by the development and deployment of an asexual identity. For example, Arno’s response to the question, ‘what does asexuality mean to you?’ is divided into “definition” and “what it does in [their] life.” They explain:

Well I like the dictionary definition of someone who doesn’t experience sexual attraction. I don’t know, it seems straightforward to me, but it never seems to be straightforward to sexual people. . . . What asexuality means to me, sorry,

(laughter); it’s a way to connect with other people identifying as asexual. It’s a way to connect to other people who experience the world the same way I do, which is pretty nice because I think it is an unusual way to experience the world.

It gives me the chance to access a community and, you know, get in touch with people who, at least as far as this is concerned, are going to see me as normal— they can think I’m weird for other reasons, that’s alright. (Arno)

To expand upon this latter half of Arno’s elaboration of asexuality, and to further articulate an asexual form-of-life, the following section of this paper focuses exclusively on the story of one of my respondents, Arial.

A

M

I A

SEXUAL

?

A

N

I

NDIVIDUAL

’

S

P

ROCESS

, I

DENTITY

, & F

ORM

-

OF

-L

IFE

Am I asexual?

The definition of asexuality is "someone who does not experience sexual attraction." However, only you can decide which label best suits you. Reading this FAQ and the rest of the material on this site may help you decide whether or not you are asexual. If you find that the asexual label best describes you, you may choose to identify as asexual. (AVEN: FAQ)

There is no reason why you have to identify as just one thing. . . . You could make up your own entirely new identity. . . . Whether or not you fit the definition of asexuality, you're welcome in the asexual community. (AVEN: FAQ)

Arial’s self-narrative of discovering, formulating, and eventually employing an asexual identity exemplifies many of the findings I have suggested, while it unravels a few of the

A SEXY S TORY

39 theoretical complexities of understanding what is asexuality by examining an individual’s repeated practice of asking ‘Am I asexual?’ I’ll begin my retelling of their narrative with the initial encounter with asexuality that brought them to AVEN and with a brief background of the previous conflict that will help contextualize this event.

Arial was seventeen at the advent of their asexual-self and had been in a relationship for about two-and-a-half years. “I just couldn’t like, you know, take having to compromise any more,” Arial explains; “I knew I didn’t want the same things that my partner did . . . I knew I didn’t think about him in the same way that he thought about me.” If we recall from above, the realization that “love and sex . . . tend to go hand and hand for sexual people,” which replaced their previous understanding of sex as “just something you did . . . when you felt aroused or something, when the mood took you,” was an event that problematized their sense-of-self in sexual relationships with others. After being “single for about a year” they “started flirting with this other guy and he wanted to take things further—but again, [they weren’t] interested.” Arial narrates their experience of one day overhearing asexuality referenced:

I overheard two people having a conversation where they were discussing a friend of theirs who came out as asexual, and they said ‘oh, he doesn’t like either men or women.’. . . it just things like clicked with me, and then I guess I knew I was an asexual . . . as soon as I heard it I knew that was what I was.