For a more comprehensive approach, the authorities may wish to go

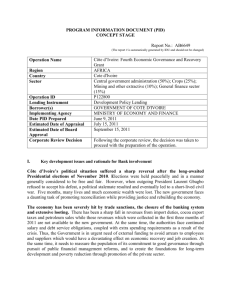

advertisement