Title: Preparing Teachers for Management and Leadership of Multi

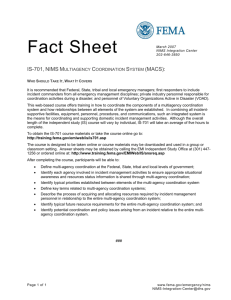

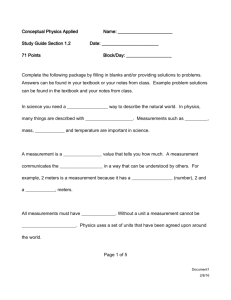

advertisement