2013

Macroeconomics 2020

Natalie Parisi

[MACROECONOMICS, FISCAL

POLICY, AND THE BUDGET

SEQUESTRATION]

Macroeconomics Term Paper: A Look at the Impact of Fiscal Policy’s

Budget Sequestration

Macroeconomics, Fiscal Policy, and

Budget Sequestration

Defining Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics is a portion of economics and it is a broad field of study. It is one of the two disciplines

used to explore an economy. It deals with the performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of

an economy as a whole, rather than as individual markets. This includes regional, national, and global

economies (Blaug, 1985).

Macroeconomists study GDP, unemployment rates, and price indexing to understand how the

whole economy functions. They look at these through aggregated indicators. Macroeconomists develop

models that explain the relationship between such factors as national income, output, consumption,

unemployment, inflation, savings, investment, international trade and international finance (Sullivan

and Sheffrin, Pg. 57).

Macroeconomic models and their forecasts are used by both governments and large

corporations to assist in the development and evaluation of economic policy and business strategy

(Bouman, 2011).

Macroeconomic policy is usually implemented through two sets of tools: fiscal and monetary

policy. Both forms of policy are used to stabilize the economy, which usually means boosting the

economy to the level of GDP consistent with full employment (Mayer, Pg. 495).

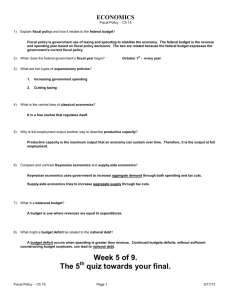

Identifying and Defining the Role of Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy is the use of federal government expenditures and revenues from

taxation used as instruments to influence the economy. If the economy is

producing less than potential output, government spending can be used

towards idle resources and will hopefully result in boosting output (Miller, Pg. 278). Government

spending does not have to make up for the entire output gap. There is a multiplier effect that boosts the

impact of government spending (Miller, Pg. 265-266).

Fiscal policy headed by the government has proven to be financially unstable because the

government has a much harder time properly financing the economy, due to the fact it is difficult to find

the necessary resources to fund the economy (Mankiw, 1990). Add to that the increased budget deficit

and the continued funds spent through government fiscal policy and you have a financial disaster for

future generations to deal with, not to mention the effects on our economy today and in the near

future.

Introduction of the Budget Sequestration

One tool that has been introduced and implemented to help with this problem of financing the economy

is the budget sequestration. Sequestration is a fiscal policy procedure adopted by Congress to deal with

the federal budget deficit. It is the massive automatic spending cuts to U.S. defense and non-defense

spending. In simple terms, it's a way of forcing cutbacks in spending on government programs and then

using that money to pay down the deficit (Koba, par. 1). The deficit refers to the difference between

government receipts and spending in a calendar year.

Sequestration first appeared in the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Deficit Reduction Act of 1985.

The Reduction Act of 1985 aimed at cutting the budget deficit, which at the time was the largest in

history, and provided for automatic spending cuts, referred to as sequesters, if the deficit exceeded a

set of fixed deficit targets. The act did provide a balanced federal budget for a year, but it failed to

permanently keep budget deficits from growing (Johnson, par. 1).

Sequestration is now in Play

Sequestration is important because it was part of the 'fiscal cliff' that would have eliminated the Bushera tax cuts while implementing across-the-board cuts on certain federal programs and defense

spending. The fiscal cliff was avoided by a last minute deal in December 2012 (Koba, par. 3). The deficit

reduction sequester is designed to enforce savings of $1.2 trillion through 2021. For 2013 and each year

after that, it means roughly an $85 billion cut in defense and non-defense spending (Koba, par. 7).

Congress was unable to reach agreement on spending cuts as of January 2013, and the

sequestration was delayed until March 1, 2013 as part of the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012. This

Act was the deal that prevented the full 'fiscal cliff ' from happening (Koba, par. 3).

The delay until March was to give lawmakers more time to agree on which programs would

actually receive spending cuts, and intended to motivate both parties to an agreement, which did not

happen.

On March 1, 2013 it reached its deadline and talks to prevent it failed (Koba, par. 5).

Based on the calculations for the sequestration,

spending on government programs will be

reduced by $984 billion over that nine-year

period. The remaining amount of savings (to get

to the $1.2 trillion) will come from reduced debt

services costs, like the amount due on the debt

interest (Koba, par.8). This includes programs like

the Department of Defense, Transportation

Security Administration, Federal Aviation Administration, Internal Revenue Service, and the Food Safety

Inspection Service. Among a few others, it also affects Education (see chart), Emergency Assistance for

Disasters, Prisons, Energy and National Parks. What it doesn’t affect are programs like Medicaid, Social

Security, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Supplemental programs, Veterans Affairs, Pell

Grants, Public Trust Funds, and the Unemployment Trust Fund (OBM Report).

The Bottom Line of the Sequestration

While the money diverted might help reduce the government deficit, there are fears that drastic cuts in

government spending could slow down U.S. economic growth.

As reported by The Office of Budget and Management, which is non-partisan and helps the

President set the budget, sequestration results might differ based on changes in law and ongoing legal,

budgetary, and technical analysis (Koba, par. 34).

But the report leaves no question that the sequestration would be "deeply destructive to

national security, domestic investments, and core government functions (OMB Report)."

There is plenty of argument between the two parties as to

where the cuts need to happen. Democrats want cuts to non-defense

spending, while Republicans want cuts to come from Social Security

and Medicare, Medicaid, and on limiting defense (Koba, par.32).

Since no agreement was reached by March 1, the president started

sending out furlough notices to government workers on Monday, March 4.

How This Applies to Me

I work for JetBlue Airways as a reservations crewmember and for weeks there have been threats of the

looming sequestration and its impact on Air Traffic Control.

On April 21, while working my normal shift, I received an email stating that, “due to the

sequestration federal budget cuts, the FAA has(d) begun implementing across-the-board cuts to staffing

at all ATC Centers, Tracons, and U.S. airport towers effective immediately, Sunday, April 21, 2013

(email#1 attached).” The email went on to say that the impact would be unknown for a few days, but to

expect significant delays.

For the past several days I’ve dealt directly with the impact. Hundreds of delayed flights and

thousands of angry customers wanting answers for something they were not even aware of. I explained

over and over that due to the budget sequestration the amount of security personnel and air traffic

controllers had declined but the amount of aircraft in flight operation had not changed. I’ve had to

explain how that impacts screening line wait times and flight schedules. I have made several

recommendations, at the urging of our Executive Staff, for customers to reach out to their

representative and senators in Congress through the Don’t Ground America website. I also encouraged

people to reach out to the DOT and the FAA letting them know of the opposition to the furloughs that

are negatively affecting the airline industry (email#2 attached).

It didn’t take long. On April 26th, Congress passed a Bill to end the FAA furloughs. I can’t wait for

operations to resume as normal and for the airline industry to get back on schedule (email#3 attached).

The sequestration isn’t going to have a positive response from everyone. No matter how

government chooses to cut spending through this program, someone will be affected in a negative way.

Unfortunately it has to happen. The real question is what cuts have the least amount of negative impact

to the economy for individuals and businesses. This sequestration only benefits the government in the

short-run. It may have a positive end result in the long-run, but people aren’t willing to give up today for

what “might be” tomorrow.

Works Cited

Blaug, Mark (1985), Economic Theory in Retrospect, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521-31644-8. Web. 25 Apr. 2013.

Bouman, John (2011), Principles of Macroeconomics -Comprehensive Principles of Microeconomics and

Macroeconomics, Columbia, Maryland. Web. 27 Apr. 2013.

Johnson, Paul M. “A Glossary of Political Economic Terms,” Department of Political Science, (2005):

Auburn University. Web. 27 Apr. 2013.

Koba, Mark. “Sequestration.” CNBC. NBC Universal, 14 Jan. 2013. Web. 25 Apr. 2013.

Mankiw, N. Gregory. "A Quick Refresher Course in Macroeconomics". Journal of Economic Literature 28

(4): Dec. 1990. p. 1645–1660. Web. 25 Apr. 2013.

Mayer, Thomas (2002). "Role of Monetary Policy". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard. An Encyclopedia of

Macroeconomics. Northhampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 495–499. Print.

Miller, Roger L. Economics Today: The Macro View. 16th ed. Boston: Addison-Wesley, 2012. Print.

Sullivan, Arthur; Steven M. Sheffrin (2003), Economics: Principles in action, Upper Saddle River, New

Jersey 07458, Pearson Prentice Hall, p. 57. Print.

Images:

http://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/2011/11/bca-sequester

http://www.debt.org/2013/02/18/sequestration/

http://www.npr.org/2013/03/01/173170211/double-take-toons-sequestration-frustration