WSI Brainstorming and Research

How do I get started on my essays?

WSI Workshop, SURP

Sept 17 & 18, 2012

Jessica Wilczak

1. Writing is a process!

This process is not necessarily linear. For instance, you might start gathering information, and then realize that you have to go back and change your thesis because you don’t have enough evidence to support your original idea. Today we’re focusing on the first three steps. Note that only step 6 actually involves writing!

1.

Read the assignment- Make sure you know what it is asking you to do! Highlight key verbs (explain, compare, define, etc.). Ask the professor/ TA questions to clarify!

2.

Prewriting- Active reading (&active listening during lectures!), brainstorming, freewriting, talking with friends, developing some good questions to guide your research, and formulating a tentative thesis statement.

3.

Gathering information (research!)- Where do I get information? How do I evaluate it?

4.

Developing the thesis

5.

Outlining the essay

6.

Drafting the essay

7.

Revising and editing

2. Research

The library is your friend! Did you know that there is a subject librarian and subject research guides for urban planning? https://www.runner.ryerson.ca/Library/guides/view/?guide=534

Search operators are words used to search library databases:

AND: limits your search to items that contain both keywords (cycling AND Toronto)

OR: broadens your search to items that contain either or both keywords (cycling OR biking)

NOT: narrows your search to items that contain only the first keyword (cycling AND Toronto NOT

safety)

$*?: allows you to broaden your search by including variant spellings (bik*)

3. Evaluating your sources

You cannot cite Wikipedia as a source! It’s ok to start here to get a broad picture, but you need to use good

(=reliable, current, and useful) sources for academic papers. These rules apply to all sources, whether they are online or print materials:

✔

Reliable: Check the author’s credentials and affiliations. Check for citations: a reliable source will always tell you where the facts and figures are coming from. Finally, find out about the publication: what organization is it affiliated with, and is there an obvious bias?

✔

Current: Check the publication date. Generally, the more current the better.

✔

Useful: Ask who the audience is. Is it too general? Too technical? A popular magazine like Maclean’s might give you information that is too general, while a scientific journal like The New England Journal of Medicine might provide information that is too technical for your paper.

Note: Dalhousie University has a good guide for evaluating web resources: http://libraries.dal.ca/using_the_library/tutorials/evaluating_web_resources/6_criteria_for_websites.html

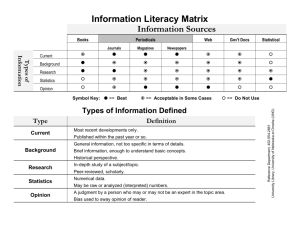

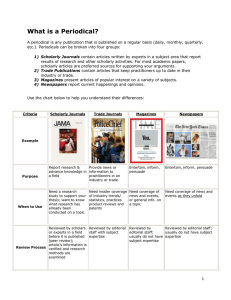

4. Scholarly journals vs popular magazines

A scholarly journal is generally one that is published by and for experts. In order to be published in a scholarly journal, an article must first go through the peer review process in which a group of widely acknowledged experts in a field reviews it for content, scholarly soundness and academic value. In most cases, articles in scholarly journals present new, previously un-published research. Scholarly sources will almost always include:

Bibliography and footnotes

Author's name and academic credentials

As a general rule, scholarly journals are not printed on glossy paper, do not contain advertisements for popular consumer items and do not have colorful graphics and illustrations (there are, of course, exceptions).

Popular magazines range from highly respected publications such as Scientific American and The Atlantic

Monthly to general interest newsmagazines like Newsweek and US News & World Report. Articles in these publications tend to be written by staff writers or freelance journalists and are geared towards a general audience. Articles in popular magazines are more likely to be shorter than those in academic journals. While most magazines adhere to editorial standards, articles do not go through a peer review process and rarely contain bibliographic citations.

5. Exercise

If you were writing about the relationship between human activity and the temperature of the earth, whose work would you choose to include in your paper? Look for clues that suggest their level of expertise and/or bias.

A . An atmospheric physicist at Winston University and founder of the Science and Environmental Policy

Project, a think tank on climate and environmental issues.

B . A Washington Post staff writer who was written articles such as "Arctic Ice Shelf Crumbles Into Sea," "In

Infrastructure Debate, Politics Is Key Player," and "President's Reform Efforts Get Results."

C . Current president of Greater Chipiwick Environmental Club, and publisher of a Web site that discusses the major causes of global warming in the last 100 years.

Select one of the following sources as most useful for a research paper on the current use of primates in scientific

laboratories:

A . "Monkeys in our Labs," by Scott Gottieber, a USA Today staff writer. Published in USA Today Dec 15, 1989.

Includes chart, "Number of Test Primates in the US, 1975-1985."

B . Laboratory Primate Advocacy Group website. LPAG is a nonprofit organization. Website last updated in

2011. "LPAG believes that the laboratory is no place for monkeys and nonhuman great apes."

C . "Better numbers on primate research," by Constance Holden. Published by the American Association for the

Advancement of Science. Appeared in Science, a scholarly publication, on March 30, 2011.