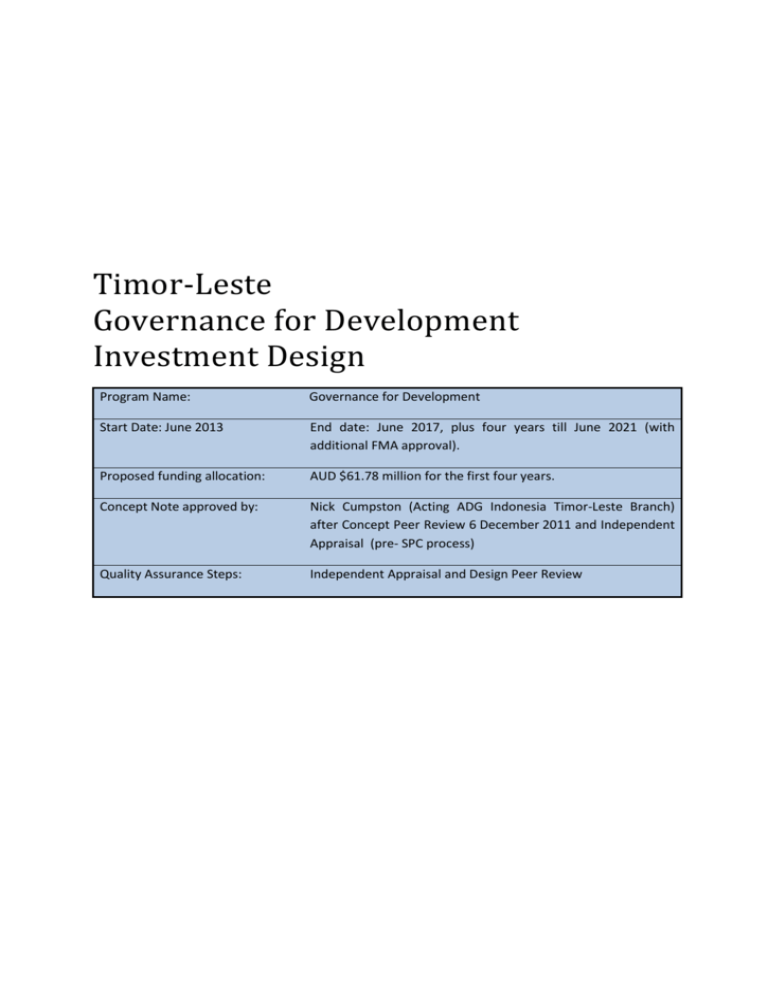

Governance for Development - Department of Foreign Affairs and

advertisement