Week 09_Lecture_Notes_Digestive System - TAFE-Cert

advertisement

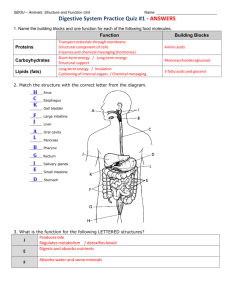

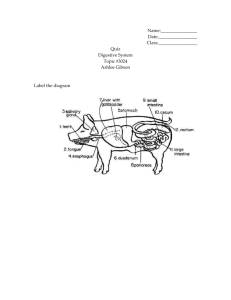

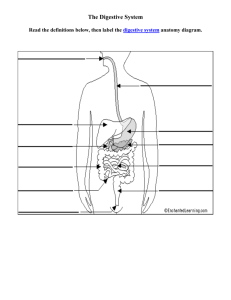

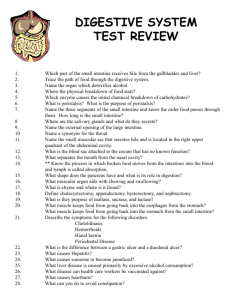

HLTAP301A ANATOMY & PHYSIOLOGY LECTURE 11 - THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM The digestive system takes in food, breaks it down into nutrient molecules and absorbs them into the bloodstream, and then rids the body of the indigestible remains. Food choices can have an effect on our health. Biologic drives for foods high in fat and simple carbohydrates (or sugars) played an important part in early human survival. These foods, which are rare in nature, provide quick and sustaining energy sources. In today’s society, we still have this biologic craving for fats and sugars, even though we no longer expend the energy that they provide. The result is an epidemic of obesity. Emotional eating is one type of substitute for lack of touch stimulation and loving relationships with others. Foods such as chocolate and other fat/carbohydrate combinations generate serotonin and other ‘feel-good’ neurochemicals just as effectively as a hug does. Eating food is often at the heart of social rituals – what would Christmas be without all the food? Healing practices usually involve the ingestion of herbs. Mating behaviours involve food and the act of eating stimulates our lips and tongue and provides comfort and sensory stimulation. The organs of the digestive system are broken in to two categories – those forming the alimentary canal and the accessory digestive organs. The alimentary canal breaks food down into smaller fragments and absorbs those fragments through its lining into the blood. The accessory organs (teeth, tongue, salivary glands, pancreas, liver and gallbladder) assist the process of digestive breakdown in various ways. The alimentary canal, which is also called the gastrointestinal [GI] tract (GIT), is a continuous muscular tube that winds through the ventral body cavity and is open at both ends. It’s organs are the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestine. The terminal opening is called the anus. In a cadaver, the GIT is approximately 9m long, but in a living person it is much shorter because of its relatively constant muscle tone. Food enters the digestive tract through the mouth, or oral cavity. The process is known as ingestion. The oral cavity is a mucous membrane-lined cavity, with the lips protecting its anterior opening, the cheeks forming its lateral walls and the hard and soft palate forming its roof. The area contained by the teeth is the oral cavity proper. The muscular tongue occupies the floor of the mouth and is anchored by the frenulum, a fold of mucus membrane which limits posterior movement. 14/3/16 1 of 4 LECTURE 11 HLTAP301A ANATOMY & PHYSIOLOGY Children born with an extremely short frenulum are referred to an ‘tongue-tied’ and usually have distorted speech because of the restricted movement of the tongue. This condition can be repaired by surgically cutting the frenulum. The paired palatine tonsils are located posterior to the soft palate and the lingual tonsils cover the base of the tongue just beyond. They are part of the body’s defense system and when they become inflamed and enlarged, the partially block the entrance into the pharynx, making swallowing difficult and painful. As food enters the mouth, the closed lips and cheeks hold the food between the teeth during chewing. The tongue constantly mixes food with saliva during chewing and initiates swallowing. Papillae containing taste buds (taste receptors) are found on the tongue surface, allowing use to enjoy and appreciate food as it is eaten. From the mouth, food passes posteriorly into the pharynx. Actually swallowing food is a complex process that requires the coordinated activity of the tongue, soft palate, pharynx and esophagus – it is also the first step in propulsion (step 2 in the digestive process). The buccal phase, which is voluntary, occurs in the mouth – the food is chewed and mixed well with saliva to form a bolus. The second phase, the pharyngeal-esophageal phase, is involuntary. The parasympathetic nervous system controls this phase – the tongue blocks off the mouth, the soft palate closes off the nasal passages. The larynx rises and the epiglottis folds back to close off the respiratory passageway. Food is moved through the pharynx into the esophagus by wavelike peristaltic contraction of the muscle walls – first the longitudinal muscles contract then the circular muscles contract. The esophageal sphincter relaxes to allow food past and then contracts again as the larynx and epiglottis return to their original position. The esophagus (also known as the gullet) runs from the pharynx through the diaphragm to the stomach and is about 25cm long. The entire lining of the GIT is a mucous membrane made up of three layers of tissue – epithelium, connective tissue and smooth muscle. The walls of the alimentary canal organs from the esophagus to the large intestine are made up of the same four basic tissue layers – the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa and the serosa. The mucosa is the innermost layer that lines the cavity of the organ. The submucosa is a soft connective tissue layer that contains blood vessels, nerve endings, lymph nodules and lymphatic vessels. The muscularis externa is a double layer of muscles – the inner layer is circular and the outer layer is longitudinal smooth muscle cells. The serosa is also known as the visceral peritoneum. 14/3/16 2 of 4 LECTURE 11 HLTAP301A ANATOMY & PHYSIOLOGY The abdominal cavity (or ventral cavity) is lines with a mucous membrane known as the peritoneum that prevents friction. The parietal peritoneum lies against the body wall and the visceral peritoneum surrounds each organ. Organs that are only covered with peritoneum on the anterior surface are known as retroperitoneal. The stomach, a sac-like organ that is actually an enlargement of the GIT, is approximately 25cm long and can hold up to 4 litres of food when full. When it is empty, it collapses inward on itself and it’s mucosa is thrown into large folds called rugae. Food enters the stomach from the esophagus through the cardioesophageal sphincter. Apart from the usual two muscle layers, the stomach has a third oblique layer in the muscularis externa that allows food to not only be moved along but to be churned, mixed and pummeled, physically breaking it down to small fragments. This process is known as mechanical digestion. The lining of the stomach is dotted with deep gastric pits which lead into gastric glands that secrete a fluid known as gastric juice – about 2-3 litres is produced every day. Asprin and alcohol are absorbed through the stomach, but everything else is broken into smaller fragments and after the food has been processed in the stomach, it looks like lumpy, thick cream, and is known as chyme. The chyme enters the small intestine through the pyloric sphincter. The small intestine is the major digestive organ of the body, a muscular tube that is about 2m in length (in a living person). It is suspended from the posterior abdominal wall by the mesentery. The small intestine is divided into three parts – the duodenum, the jejunum and the ileum. The duodenum, the shortest part of the small intestine at 25cm long, curves around the head of the pancreas. Bile ducts and the pancreatic duct join at the hepatopancreatic ampulla and bile (which is produced by the liver) and pancreatic juice (obviously produced by the pancreas) enter the duodenum. Almost all food absorption takes place in the small intestine, and the jejunum, at 2.5m long, is the major structure where this absorption takes place. Glands located in the walls of the jejunum provide secretions for the digestive process. The ileum (3.6m long) connects the small intestine to the large intestine at the ileocecal valve. The walls of the small intestine have three structures that increase the absorptive surface – microvilli, villi and circular folds. Food reaching the small intestine is only partially digested. This is where chemical digestion intensifies. The circular folds of the small intestine decrease in number towards the end of the small intestine and local collections of lymphatic tissue (Peyer’s patches) increase – this occurs because the remaining food residue that reaches the end of the small intestine contains large numbers of bacteria, which must be prevented from entering the bloodstream, where possible. 14/3/16 3 of 4 LECTURE 11 HLTAP301A ANATOMY & PHYSIOLOGY The large intestine is about 1.5m in length ands it’s major function is to absorb water from the indigestive food residue, thereby forming feces to be eliminated from the body. The large intestine is broken into several parts – the cecum, the appendix, the colon, the rectum and the anal canal. The cecum is a blind pouch that receives the digested matter from the ileum. The appendix is a potential trouble spot, because it is an ideal area for bacteria to accumulate and multiply. Inflammation of this area is called appendicitis and if untreated, can lead to peritonitis, which can be fatal. The colon is divided into distinct regions – the ascending colon, the transverse colon, the descending colon and the sigmoid colon. The rectum leads to the anal canal, which has an internal involuntary sphincter and an external voluntary sphincter which opens and closes the anus during defecation. Accessory Digestive Organs The pancreas produces a wide spectrum of enzymes, responsible for food breakdown which are secreted into the duodenum via the pancreatic ducts. It is also an endocrine gland, which will be discussed in a later lecture. The liver is the largest gland in the body and one of the body’s most important organs. It has many metabolic and regulatory roles, but it’s digestive role is to produce bile, which leaves the liver via the common bile duct. The gallbladder stores and concentrates bile, releasing it as required. If the bile becomes too concentrated, the cholesterol is contains may crystallize, forming bilestones which are extremely painful. The salivary glands excrete saliva, which is a mixture of mucus and serous fluid which contains salivary amylase and substances that inhibit bacteria. 14/3/16 4 of 4 LECTURE 11