Dartmouth-Chen-Moolenijzer-Aff-UCO-Round1

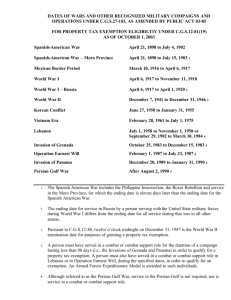

advertisement